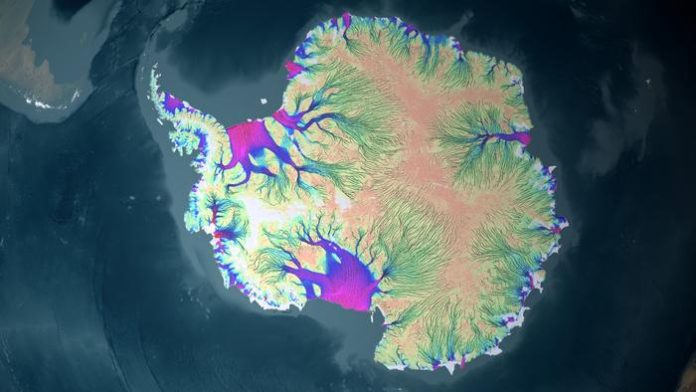

As the planet warms, the Antarctic ice sheet is melting and contributing to sea-level rise around the globe.

Antarctica holds enough frozen water to raise global sea levels by 190 feet, so precisely predicting how its ice sheet will move and melt now and in the future is vital for protecting coastal areas.

However, most climate models struggle to simulate the movement of Antarctic ice accurately due to sparse data and the complexity of interactions between the ocean, atmosphere, and frozen surface.

In a new study, researchers at Stanford University used machine learning to analyse high-resolution remote-sensing data of ice movements in Antarctica for the first time.

Using AI to understand our climate reveals some of the fundamental physics governing the large-scale movements of the Antarctic ice sheet and could help improve predictions about how the continent will change in the future.

Dynamics of the Antarctic ice sheet

The Antarctic ice sheet, Earth’s largest ice mass and nearly twice the size of Australia, acts like a sponge for the planet, keeping sea levels stable by storing freshwater as ice.

To understand the movement of the Antarctic ice sheet, which is shrinking more rapidly every year, existing models have typically relied on assumptions about ice’s mechanical behaviour derived from laboratory experiments.

However, Antarctica’s ice is much more complicated than what can be simulated in the lab. Ice formed from seawater has different properties than ice formed from compacted snow, and ice sheets may contain large cracks, air pockets, or other inconsistencies that affect movement.

“These differences influence the overall mechanical behaviour, the so-called constitutive model, of the ice sheet in ways that are not captured in existing models or in a lab setting,” explained Ching-Yao Lai, an assistant professor of geophysics in the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and senior author of the paper.

Instead, the team built a machine learning model to analyse large-scale movements and thickness of the ice recorded with satellite imagery and airplane radar between 2007 and 2018.

The researchers asked the model to fit the remote-sensing data and abide by several existing laws of physics that govern the movement of ice, using it to derive new constitutive models to describe the ice’s viscosity – its resistance to movement or flow.

Compression vs strain

The researchers focused on five of Antarctica’s ice shelves – floating platforms of ice that extend over the ocean from land-based glaciers and hold back the bulk of Antarctica’s glacial ice.

They found that the parts of the ice shelves closest to the continent are being compressed, and the constitutive models in these areas are fairly consistent with laboratory experiments.

However, as ice gets farther from the continent, it starts to be pulled out to sea. The strain causes the ice in this area to have different physical properties in different directions.

“Our study uncovers that most of the ice shelf is anisotropic,” said first study author Yongji Wang, who conducted the work as a postdoctoral researcher in Lai’s lab.

“The compression zone – the part near the grounded ice – only accounts for less than 5% of the ice shelf. The other 95% is the extension zone and doesn’t follow the same law.”

Accurately understanding the movement of the Antarctic ice sheet is only going to become more important as global temperatures increase – rising seas are already increasing flooding in low-lying areas and islands, accelerating coastal erosion, and worsening damage from hurricanes and other severe storms.

AI’s advantage in climate modelling

The study authors don’t yet know exactly what is causing the extension zone to be anisotropic, but they intend to continue to refine their analysis with additional data from the Antarctic continent as it becomes available

Researchers can also use these findings to understand the stresses that may cause rifts or calving or as a starting point for incorporating more complexity into ice sheet models.

This work is the first step toward building a model that more accurately simulates the conditions we may face in the future.

The researchers believe that combining observational data and established physical laws with deep learning could be used to reveal the physics of other natural processes with extensive observational data.

They hope their methods will assist with additional scientific discoveries and lead to new collaborations with the Earth science community.

Lai concluded: “We are trying to show that you can actually use AI to learn something new.

“It still needs to be bound by some physical laws, but this combined approach allowed us to uncover ice physics beyond what was previously known and could really drive new understanding of Earth and planetary processes in a natural setting.”