Astronomers at the Royal Astronomical Society utilised an animated model of the Milky Way to investigate dust, allowing them to determine groundbreaking conclusions regarding our Galaxy.

A research team from the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS) has revealed an interactive tool that comprises the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission data, as well as other science data sets, to create an animation to model dust in the Milky Way.

This study was recently presented at the National Astronomy Meeting (NAM, 2022) at the University of Warwick.

The cumulative build-up of dust

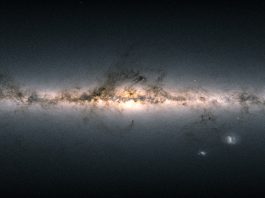

The animation demonstrates the cumulative build-up of dust observed from Earth to 13,000 lightyears towards the galactic centre – approximately 10% of the overall distance across the Milky Way. Close by, dust swirls all around, however, further out, the concentration of dust along the galactic plane becomes clear. The animation also uncovered two windows, one above and one below the galactic plane.

“Dust clouds are related to the formation and death of stars, so their distribution tells a story of how structures formed in the Galaxy and how the Galaxy evolves,” explained Nick Cox, Coordinator of the EXPLORE project, which is developing the tools. “The maps are also important for cosmologists in revealing regions where there is no dust and we can have a clear, unobstructed view out of the Milky Way to study the Universe beyond, such as to make deep field observations with Hubble or the new James Webb Space Telescope.”

Creating the animated model of the Milky Way

The tools utilised to create the animation combined data from the Gaia mission and the 2MASS All Sky Survey. The tools are part of a suite of applications designed to support studies of stars and Galaxies, as well as lunar exploration, and have been developed through funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Programme.

“State-of-the-art machine learning and visual analytics have the power to greatly enhance scientific return and discovery for space science missions, however, their use is still relatively novel in the field of astronomy,” concluded Albert Zijlstra, from the University of Manchester and a researcher on the EXPLORE project.

“With a constant stream of new data, such as the recent third release of Gaia data in June 2022, we have an increasing wealth of information to mine – beyond the scope of what humans could process in a lifetime. We require tools like the ones we are developing for EXPLORE to support scientific discovery, such as by helping us to characterise properties within the data, or to pick out the most interesting or unusual features and structures.”