In a groundbreaking discovery, a team of astronomers has identified a gigantic supernova explosion caused by two stars crashing together for the first time ever.

The researchers have obtained evidence that either a black hole or a neutron star has rocketed into the core of its companion star, resulting in a dramatic supernova explosion of its neighbour. This interstellar phenomenon has long been hypothesised about, but until now, had never been observed.

The researchers made their supernova explosion discovery thanks to data procured from the Very Large Array Sky Survey (VLASS), a multi-year project that utilises the National Science Foundation’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA).

Dillon Dong, a graduate student at Caltech and lead author on a paper reporting the discovery, said: “Theorists had predicted that this could happen, but this is the first time we’ve actually seen such an event.”

Intergalactic clues of a supernova explosion

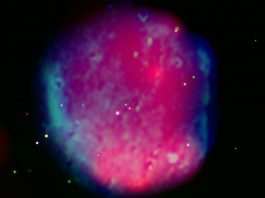

The astronomers’ first indication of a supernova explosion occurred when analysing images from VLASS, a project that has been conducting observations of the Universe since 2017. They identified an object that was brightly emitting radio waves but had not been located in an earlier VLA sky survey called Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty centimetres (FIRST).

The team conducted follow up observations of the object dubbed VT 1210+4956 using Hawaii’s VLA and Keck telescope, finding that the radio emission was originating from the outskirts of a dwarf, star-forming galaxy located 480 million light-years from Earth. Instruments aboard the International Space Station (ISS) has also detected bursts of X-rays from the object in 2014. This comprehensive data enabled the team to unravel the series of events that led to the demise of the two massive stars.

The timeline of the stars’ deaths

The two stars were born as a binary pair – a common occurrence among stars much larger than our Sun, meaning they closely orbit each other. One of the stars was more massive than the other, therefore evolving through its lifetime much faster and resulted in a supernova explosion, leaving in its wake a black hole or a superdense neutron star.

Subsequently, the black hole or neutron star exponentially grew until it was in close proximity to its companion, entering its atmosphere around 300 years ago, at which point it started spraying gas away from the companion into space. This exerted gas spiralled outwards to form a doughnut-shaped ring around the two stars called a torus.

Next, the black hole or neutron star started to permeate the stars’ core, disturbing the nuclear fusion that produces the energy that stops it from collapsing due to its own gravity, causing it to collapse. During this collapse, the core briefly formed a disk of material that closely orbited the black hole or neutron star, propelling a jet of material at close-to-light speeds that drilled through the star.

Dong said: “That jet is what produced the X-rays seen by the MAXI instrument aboard the International Space Station, and this confirms the date of this event in 2014. The collapse of the star’s core caused it to explode as a supernova, following its sibling’s earlier explosion. The companion star was going to explode eventually, but this merger accelerated the process.”

In 2014, the ejected material moved considerably faster than the material thrown earlier from the companion star, so by the time VLASS observed the object, the supernova explosion was already colliding with that material, triggering the bright radio emission located by the VLA.

Gregg Hallinan, a Professor of Astronomy at Caltech, said: “All the pieces of this puzzle fit together to tell this amazing story. The remnant of a star that exploded a long time ago plunged into its companion, causing it, too, to explode. The key to the discovery was VLASS, which is imaging the entire sky visible at the VLA’s latitude – about 80% of the sky – three times over seven years.

“One of the objectives of doing VLASS that way is to discover transient objects, such as supernova explosions, that emit brightly at radio wavelengths. This supernova, caused by a stellar merger, however, was a surprise. Of all the things we thought we would discover with VLASS, this was not one of them.”