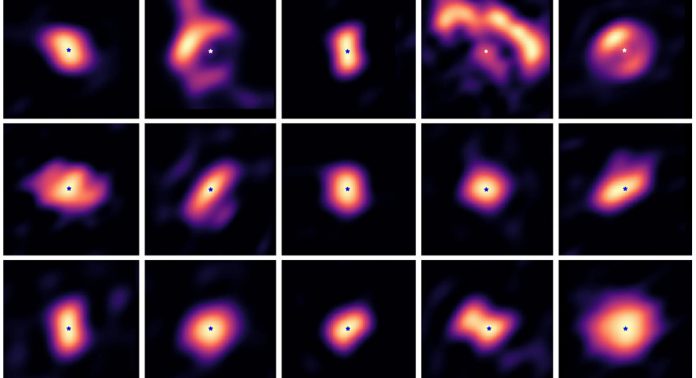

Using infrared interferometry, astronomers have successfully captured fifteen images of the inner rims of planet-forming disks.

Discovered by an international team of researchers, these planet-forming disks form around young stars and are made of dust and gas. Published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, the images shed new light on how planetary systems are formed.

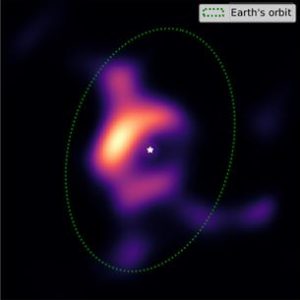

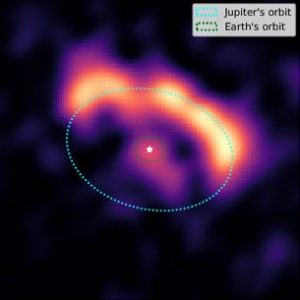

Planet-forming disks are formed in unison with the star they surround. The dust grains in the disks can grow into larger bodies, eventually leading to the formation of planets. Terrestrial planets like the Earth are believed to form in the inner regions of planet-forming disks, less than five astronomical units from the star around which the disk has formed.

Infrared interferometry of planet-forming disks

The research team created the new images at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), Chile, using a technique called infrared interferometry. Using ESO’s PIONIER instrument, researchers combined the data collected by four telescopes at the Very Large Telescope observatory. Although this technique delivers detailed information about these planet-forming disks, it does not deliver an image of the observed source.

“Distinguishing details at the scale of the orbits of rocky planets like Earth or Jupiter – a fraction of the Earth-Sun distance – is equivalent to being able to see a human on the Moon, or to distinguish a hair at a 10km distance,

“Infrared interferometry is becoming routinely used to uncover the tiniest details of astronomical objects. Combining this technique with advanced mathematics finally allows us to turn the results of these observations into images,” noted Jean-Philippe Berger of the Université Grenoble-Alpes, France, who as principal investigator of the work with the PIONIER instrument.

Inconsistencies in these findings

Researchers found some unusual spots on these images, “you can see that some spots are brighter or less bright, like in the images above: this hints at processes that can lead to planet formation. For example: there could be instabilities in the disk that can lead to vortices where the disk accumulates grains of space dust that can grow and evolve into a planet.”

The international research team will conduct additional research in order to identify the cause of these irregularities. Lead author Jacques Kluska from KU Leuven in Belgium, will also do new observations with the hopes of producing even more detail.

Kluska has expressed interest in directly witnessing planet formation within these planet-forming disks. Now, Kluska is leading a team that aims to study 11 disks around other, older types of stars also surrounded by disks of dust, since it is thought these might also sprout planets.