Curtin University’s Professor Jacques Eksteen explores the Australian lithium industry and its role in the global battery supply chain.

Lithium is most commonly used for rechargeable batteries in our mobile phones, laptops, digital cameras, home and grid energy storage, and electric vehicles (EVs). And while Australia is currently the world’s biggest lithium exporter, can the country keep up with the ever-growing rise of technology and more people turning to EVs?

In 2020, Western Australia was the largest producer of lithium, accounting for 49% of the entire world’s resources. The region was followed by Chile (22%), China (17%), and Argentina (8%). Home to the world’s largest hard rock lithium mine, Australia will continue to supply the world’s demand for lithium in 2022 and beyond.

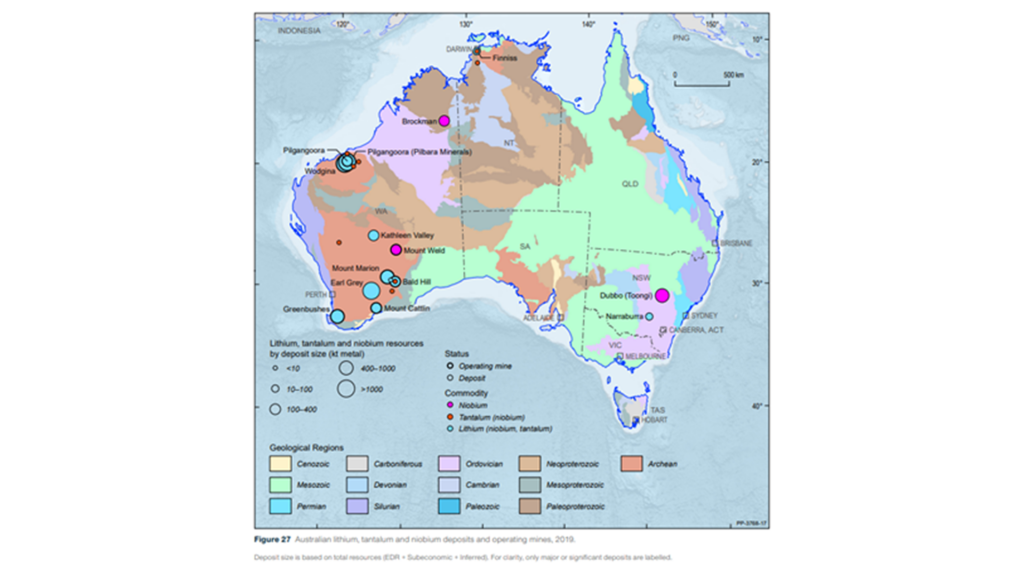

Australia’s reserves and resources of lithium

Lithium, along with tantalum and niobium, is hosted together in hard rock pegmatite deposits, mainly within Western Australia. These resources are regarded as critical minerals by many advanced economies and are listed in Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategy 2022, released by the Federal Government earlier this year. More than 84% of Australia’s lithium is hosted by four deposits: Greenbushes, Wodgina, Pilgangoora, (Pilbara Minerals Ltd), and Earl Grey.

Other resources can be found at Mount Cattlin, Mount Marion, Bald Hill, and Kathleen Valley in the Yilgarn region of Western Australia; at Wodgina and Pilgangoora (Altura Ltd) in the Pilbara region of Western Australia; and at the Grants deposit (Finniss Project) in the Northern Territory.

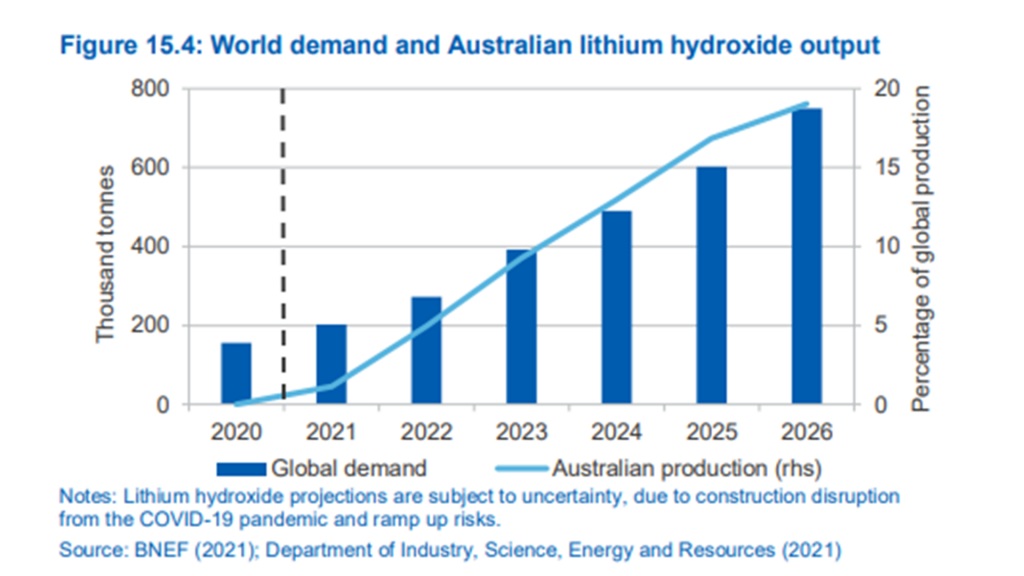

Due to the rise of lithium hydroxide development in Australia, a second refinery is currently under construction in Kemerton, set to be one of the world’s largest lithium production facilities. This is in addition to the first at Kwinana which is currently being commissioned. The Kwinana refinery has started producing hydroxide with resources from one of the existing major lithium deposits, Greenbushes. It is expected to have an 85% recovery of lithium contained in the spodumene concentrate and will have the capacity to produce approximately 45,000 tonnes of battery-quality lithium hydroxide per year. The Kwinana refinery will ultimately manufacture a product allowing the storage of renewables and will also help to lower reliance on fossil fuels, enabling approximately one million EVs to go on the road every year.

Source: The Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Office of the Chief Economist, Resources and Energy Quarterly, June 2022

A third lithium hydroxide refinery, owned by Covalent Lithium (a JV between Wesfarmers and SQM), is currently in the detailed engineering design and procurement phase and will also be constructed in Kwinana.

In later stages, the Wodgina mine may also be recommissioned with the final location for the processing of Wodgina ore yet to be determined.

Mineral Resources has a stated ambition of converting all of its spodumene into lithium hydroxide, with the plant potentially at full capacity this year.

Slow growth in EV uptake and oversupply meant decreased demand and price for lithium in 2019. As a result, Australian producers have delayed planned mine expansions and also reduced production rates. Two mine sites, Bald Hill and Wodgina, also stopped production in the second half of 2019 and were put under care and maintenance. The rapid escalation in lithium prices since the middle of 2021 (around a tenfold price increase since the lows of 2019) has renewed investment drive into lithium mineral processing and refining to battery-grade lithium hydroxide.

Tianqi Lithium Australia Pty Ltd started production of lithium hydroxide at its processing plant in Kwinana in 2019, using ore from their Greenbushes deposit. Once Tianqi is fully operational, the plant will produce about 10% of Australia’s annual battery-grade lithium hydroxide. The stage two expansion has been placed on hold temporarily.

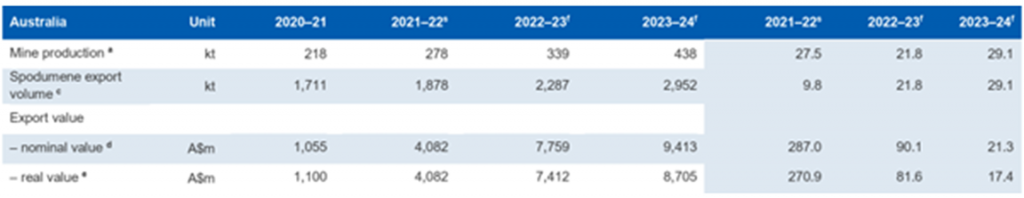

Australia’s annual production of lithium

Australia’s lithium production is forecast to rise from 278,000 tonnes in 2021–22 to 438,000 tonnes in 2023–24 with export earnings also forecast to increase from $4.1bn in 2021–22 to $9.4bn in 2023-24.

Source: The Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Office of the Chief Economist, Resources and Energy Quarterly, June 2022

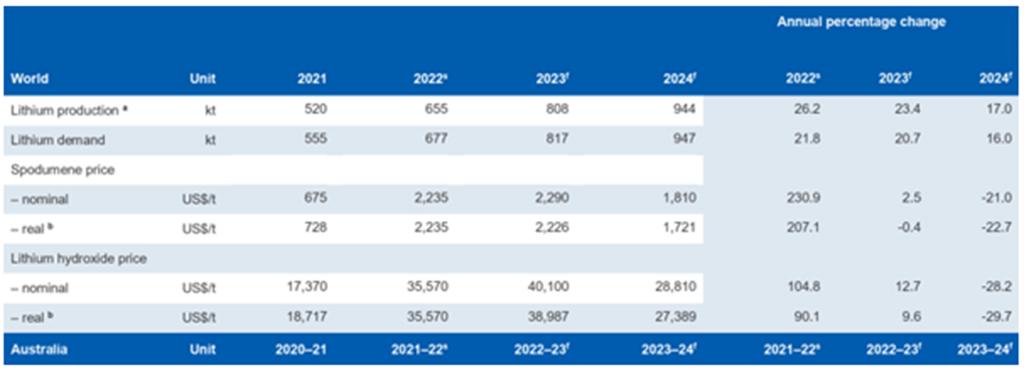

Global lithium production

Comparing lithium production in Australia and the rest of the world, during 2021-22 Australia produced 278kt of lithium, which is around half the amount produced globally.

How important is Australia’s role in the global lithium/battery supply chain?

Australia has strong access to minerals, producing eight out of nine key materials used in the battery value chain, and is the largest lithium producer.

The nation is already a leading producer of battery minerals, which presents an opportunity to leverage this strength by accessing raw materials to move further downstream. More than half of the world’s lithium is extracted in Australia, and hard rock resources are generally regarded as better suited to battery production because of the ability to refine them directly to lithium hydroxide.

As our refining and active materials segments develop, they will have access to quality resources. Australia is also a significant producer of iron (40% of global supply), manganese (23% of global supply), and vanadium (19% of global supply).

Australia’s share of nickel is smaller but substantial and BHP is currently investing in refining capacity to produce nickel sulphate at Kwinana. However, Australia has significant upside in nickel resources, particularly in the form of laterites, but would need to invest more into refining facilities to produce battery-grade nickel and cobalt salts (such as their respective sulphates).

China also plays a similarly significant role in producing battery minerals. While both Australia and China produce leading quantities of eight of the battery minerals, the two countries’ mineral strengths are complementary. Some of Australia’s strongest production of minerals, including lithium, are some of China’s weakest, and vice versa.

Australia ranks second in the world globally with 29% of the world’s economic lithium resources, behind Chile (44%), and first for the production of resources (56%).

Since the dip in lithium in 2019 due to a slow EV uptake, Australia’s production has recovered strongly. EV sales alone are expected to increase from three million in 2019 to 26 million by 2030. This, along with the projected production and export earnings, and the opening of new lithium refineries in Australia, means we are in a strong position to continue to supply lithium to the rest of the world.

Challenges facing the Australian lithium industry

Australia will most likely continue to significantly gain from lithium mining, but there could be some challenges. These could include:

- A decline in lithium’s share of the total market value;

- A negative balance of trade impact (due to the need to re-import value-added products); and

- Missed industry opportunities for innovation and commercialisation including energy trading, high-tech recycling, and grid stabilisation.

What can be done to ensure Australia continues to take the lead?

Australia is in a strong position to continue being a leader in the production and exportation of lithium. Evidence suggests that any sufficiently large battery chemical plant in Australia will be globally cost-effective, and due to the dependability of hard rock supply, would likely have more predictable operating costs per tonne (compared to brine-based lithium produced in Argentina and Chile). However, it is becoming essential to invest in lowering the carbon footprint associated with lithium production, which is a major ESG driver for international battery manufacturers and OEMs.

The Australian lithium market has many opportunities for growth. It would be beneficial to generate awareness – making sure the production and exportation of lithium are at the forefront of all levels of the Australian government. Having reliable data available on lithium and other battery minerals would also be beneficial in ensuring a good understanding of the current lithium market, what Australia is doing well, and gaps that could be leveraged.

As has been done well in China, Korea, and Japan, the key is ensuring policy settings are accurate and reliable. This could include exploring the potential for State Agreements with industry to attract further significant investment in lithium processing and value-adding, as well as funding research through universities, CSIRO, and other appropriate research organisations. Facilitating the upstream of materials handling regulations would also be beneficial in aiding the development of lithium processing.

For example, Korea and Japan, which are not lithium producers, have leveraged processing advantages and policy levers to position themselves to value-add to lithium within the global value chain.

If Australia wants to continue to lead the lithium industry, government, industry, and industry associations must collaborate and act now for a strong future in both the production and exportation of lithium, including the investment into cathode active materials such as lithium ferro phosphate (LFP) and lithium ferro manganese phosphate (LFMP), and lithiated nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM) cathode active materials co-located in suitable chemical production hubs.

Professor Jacques Eksteen

Chair, Extractive Metallurgy from the WA School of Mines: Minerals, Energy and Chemical Engineering

Curtin University

www.curtin.edu.au/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/jacques-eksteen-ba763812/

Please note, this article will also appear in the eleventh edition of our quarterly publication.