Dr Hadi Moztarzadeh, Head of Technology Trends at the Advanced Propulsion Centre UK, discusses the challenges and opportunities for the UK’s compound semiconductor supply chain, to underpin the automotive sector’s net-zero journey.

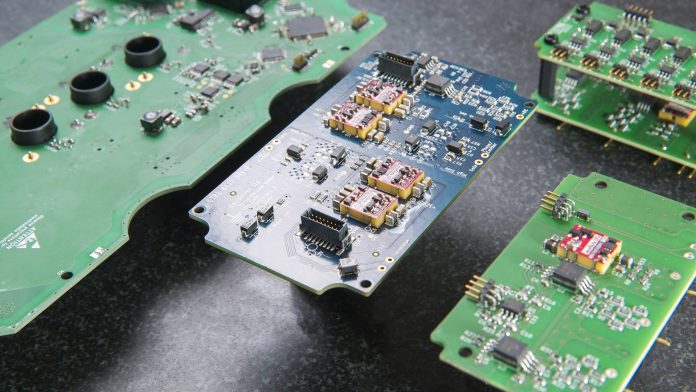

Power electronics are everywhere. They are the beating heart of the gadgets and devices we use every day and are in electronics in our home and work. Our transportation is no exception. The power steering of a vehicle needs power electronics, window mechanisms and, crucially, the electrified powertrains. In fact, power electronics are the unseen hero for all electrified drivetrains. While traditional internal combustion engines (ICE) require power electronics for the batteries to kickstart the engines into life, new electrified technologies rely much more on power electronic components for the battery and electric motor to operate.

However, over the past 18 months, there have been significant issues with the supply of semiconductors, and the automotive sector was not immune to this. In the UK, automotive manufacturers currently rely on imports from Taiwan and Singapore for most of the key materials and components for semiconductors. This has led to a decreased output from automotive manufacturers, leading to much longer lead times for new vehicles – a challenging issue for the semiconductor supply chain.

Addressing challenges in the semiconductor supply chain

With the deadline looming for the ban on the sale of diesel and petrol cars, automakers must look to ramp up production of hybrid and full electric vehicles (EVs). However, electric vehicles – both battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles – use approximately 30% more chips than ICE vehicles, meaning supplies and imports will continue to impact vehicle production.

The shortage of semiconductors was initially driven by issues and the fallout of lockdowns during the global COVID-19 pandemic, and with demand increasing for items such as IT equipment as people switched overnight to remote working scenarios, the impact is still being felt. The small number of wafer-fab producers globally and a quick, sharp increase in demand has led to shortages, with many automotive manufacturers still reporting lengthy lead times on new vehicle orders. The auto market currently accounts for around 15% of the global market for semiconductors, and this reliance will only increase as the transition to electric powertrains takes hold.

In a Guardian article published in September 2021, Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) Chief Executive Mike Hawes stated: “The impact of the semiconductor shortage on manufacturing cannot be overstated.

“Carmakers and their suppliers are battling to keep production lines rolling with constraints expected to continue well into 2022 and possibly beyond.”

So, the big question is what can be done to ease the issue, and how can the UK build a more resilient semiconductor supply chain?

The Advanced Propulsion Centre (APC), the organisation tasked by the UK government and automotive industry to accelerate the transition to low-carbon transport solutions, has conducted a significant piece of work to de-mystify the semiconductor manufacturing process and accelerate critical semiconductor supply chain development. By increasing the understanding amongst industry, the investment community and government officials, its aim is to close out gaps and onshore production, creating a robust end-to-end supply chain to support automotive manufacturing in the UK. There is currently no UK end-to-end supply chain to meet the needs of the automotive manufacturing sector.

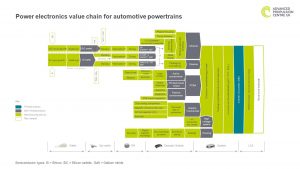

The new value chain report outlines five key stages in the manufacturing process of power electronics for automotive powertrains, from wafer substrates to full systems, and is accompanied by an insight report to put a spotlight on what focus is needed. The APC estimates that 2.3 million inverters will be needed per annum from 2035 for UK-manufactured passenger cars and vans alone. Inverters are one of three main power electronic components onboard battery electric vehicles, with a DC-DC converter and an onboard charger (OBC) making up the other two. They have the largest semiconductor content of all three due to their high power requirements.

By using compound semiconductors, the UK has a real chance of being able to onshore its own robust end-to-end supply chain. Semiconductors are a vital part of power electronics, and power electronics are fundamental to electric vehicles, particularly high-power inverters. If we are to meet manufacturing targets of zero emission vehicles on sale post-2030, we need to onshore our supply chain. We encourage industry, government, academia and the investment and trade communities to come together to anchor the journey to creating a robust UK semiconductor supply chain. The report identifies that, with a focus on silicon carbide (SiC) and gallium nitride (GaN) semiconductors, we have a credible chance of achieving this.

The message is that the UK can build a resilient supply chain and this is how it can be done, but there must be collaboration and a move to act fast. The clock is ticking.

Benefits of silicon carbide

SiC is the preferred front-runner for future electric vehicle power distribution, control, and supply management. This is particularly the case as vehicle electrical architectures are moving to 800V+, where SiC performs best. It is cost effective when its benefits are applied across the powertrain system, providing power efficiency gains, and reducing the size of motors and the battery pack.

SiC-based inverters are expected to dominate the market by 2030, reaching between 30-50% market penetration by 2025. Europe will need between 600,000 – 800,000 SiC wafers by 2030 with requirements in the UK coming in at a supply of 80,000 SiC wafers annually by 2030 to support locally-produced electric vehicles.

Close collaboration with industry experts

Numerous organisations, academia, and industry have contributed to the creation of the value chain and associated insight reports, including McLaren Applied, Clas-SiC Wafer Fab, Exawatt, Turntide, Semikron Danfoss, Dynex, Microchip, Custom Interconnect, Driving the Electric Revolution Challenge, Compound Semiconductor Applications (CSA) Catapult, National Microelectronics Institute, CSconnected, University of Warwick, University of Nottingham, and University of Bristol.

Steve Lambert, Head of Electrification at McLaren Applied, was consulted as part of the value chain project and he welcomes the final report saying: “The UK is great at the power electronics design level and there is a fantastic opportunity for local manufacturing. The market is healthy and there is demand so we now need to build the capability to do this here by investing in skills and training. The demand is for high-quality, high-performance mid-volume market – high-quality components for niche applications. This is where the UK can succeed. It will give us the differentiated products we need and, as well as providing a reliable supply to the UK-based automotive OEMs, it offers a significant export opportunity.”

The APC is already funding two large-scale collaborative R&D projects that shine a light on how to kickstart the supply chain. ‘ESCAPE’ is a £19m project led by McLaren Applied, and ‘Future BEV (Battery Electric Vehicles)’ is led by BMW. Both collaborative R&D projects are looking to develop 800 V silicon carbide inverters and are key to developing opportunities to build capability in the UK supply chain for power electronics with a real-world solution at the core.

In July 2022, the United States Senate and House of Representatives passed the CHIPS and Science Act, providing $52bn in government subsidies for research and production of semiconductors in the US. The European Commission proposed the European Chips Act in February 2022, aiming to double the European share of global microchip production by 2030 and reduce supply dependencies. The message is clear, we need to act now.

More investment needed in semiconductors

At a recent panel discussion hosted by the APC (February 2023), the panellists were confident the UK has the capability to deliver the end-to-end supply chain if support by the way of funding and investment is made available. Globally, we are seeing efforts to secure supplies and, furthermore, build in-house production capabilities with large investments internationally and vertical integration of supply chains.

Rae Hyndman, Managing Director at Clas-SiC Wafer Fab, and one of the panellists, said: “At Clas-SiC, we’ve de-risked, we have built a wafer fab from scratch. We have developed the technology, so we have done all the hard stuff. Scaling is just copying and repeating what we have already done. We need help to get access to investment to scale. We are in the right place, at the right time with the market, but funding for scaling is the challenge.”

The APC’s Technology Trends team have worked closely with key industry and academic stakeholders to create a first-of-its-kind value chain and key steps that the UK needs to take.

The report concludes that increasing local SiC semiconductor and inverter production for high-power vehicles (luxury, performance, SUVs, and HGVs), will future-proof automotive manufacturing in the UK. With 80% of the economic value held across power modules and the manufacturing of inverter systems, the UK can play to its strengths with capabilities in its domestic Tier 1 supply chain. An area that is more challenging is the lack of upstream wafer substrate manufacturing in the UK, exposing it to supply shocks and downstream production constraints. More needs to be done about this.

Further information can be found on the APC website or by contacting the Technology Trends Team.

Please note, this article will also appear in the fourteenth edition of our quarterly publication.