Professor Juhani Junttila from the Medical Research Center Oulu spoke to The Innovation Platform about research into the prevalence of coronary artery disease and autopsy findings among sudden cardiac death victims under the age of 50.

Each year, cardiovascular disease causes some 3.9 million deaths in Europe and over 1.8 million deaths in the European Union (EU). And while there is a common misconception that coronary artery disease is thought to mainly affect the elderly population, its significance among younger people is now starting to be recognised, with autopsies of young adults revealing advanced cardiac disease in numerous instances. Indeed, coronary artery disease is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death, even among younger people.

The Innovation Platform’s International Editor, Clifford Holt, spoke to Professor Juhani Junttila from the Medical Research Center Oulu, about new and on-going research into the prevalence of coronary artery disease and autopsy findings among sudden cardiac death victims under the age of 50, which has found that 44% of sudden cardiac deaths among people under the age of 50 were caused by coronary artery disease.

Could you begin by describing the current situation with regards to the causes of sudden cardiac deaths among young and middle-aged people under the age of 50 and what your recent project was designed to achieve?

We have, in fact, been studying sudden cardiac deaths for over 20 years now, having started to collect autopsy data on this population back in in 1998. From then until the end of 2017, we were able to collect autopsy data on almost 6,000 people who have died as a result of sudden cardiac deaths.

This is an impressive number and was enabled because in Finland the law requires an autopsy to be undertaken in every case of sudden death when the cause is unknown and if the patient had not been treated by a physician for a specific illness. Of course, autopsies are performed for other reasons, too, but this law means that there is a high percentage of autopsies being conducted on people who have suffered sudden cardiac deaths.

It is very important that autopsies are performed on people who have died suddenly because almost 30% of them may have died from something other than sudden cardiac reasons, such as cerebral haemorrhage or a pulmonary embolism, for instance. An autopsy is therefore used to verify the causes of death. To study the causes of death in society, in 1998 we started to collect the data on this population.

It is important to note that this population in Finland is one of the largest of its kind in the world, with there being quite a large population in the UK, although for younger people, and another in the US, which has data on a large number of sudden cardiac arrest survivors.

Our goal is to essentially use the data we have to better understand the reasons and risk markers – both genetic and otherwise – behind sudden cardiac deaths so that we can go on to potentially reduce the number of instances in society.

The recent study you have referred to is one part of this larger effort. Here, it was interesting to see that in this population of young and middle-aged people under the age of 50, the risk of coronary disease related sudden cardiac death is already there. This is at odds with the widely-held belief that the events related to coronary disease do not start until a person is elderly. This is incorrect; coronary disease and its events begin to manifest when people are aged just 30 and, indeed, can prove fatal from an early age.

How did you approach the research? What challenges did you encounter/overcome – perhaps in terms of both the research itself as well as any data protection or patient confidentiality issues?

Conducting the research is relatively straightforward as the people we are studying are deceased, which means that things like GDPR no longer apply to them. Of course, we have to follow typical ethical guidelines, and we received ethical approval from the National Institute of Health and Welfare at the beginning of the study.

Neither were there many obstacles to overcome in working with the forensic pathology department, other than ensuring that we found people who were interested in what we were doing and what we wanted to achieve, which was easy enough.

Aside from these minor hurdles, we were able to look through the records from the autopsies, where the data is recorded meticulously; when an autopsy is conducted, it is seen as both a legal and a medical procedure, which means that the pathologist won’t simply stop when they find the cause of death. Rather, they will continue until the procedure is complete, and this means that we had both robust and large quantities of data at our disposal.

What were your main findings/results? Were you surprised by anything?

We have been surprised by several things since we began this research, and not simply with regards to the most recent paper. Perhaps one of the most important is that over the last few years we have found that while coronary diseases is the most common cause for sudden cardiac death – accounting for some 70-75% of all cases – there is an increasing number of non-ischemic causes. These include different diseases there that are not yet well documented or understood, such as cardiomyopathies.

Furthermore, in the past it was widely believed that inherited cardiomyopathies are the majority of non-ischemic causes, but that is not actually true; we have discovered that the majority of non-ischemic conditions had acquired diseases such as hypertension and obesity as a cause of the myocardial disease.

Of course, obesity has been a growing problem in Western societies for some time now, and this is evident in the increasing number of obese people in the population we have studied. We have seen an increase in the number of deceased people who had a BMI of over 35 undergoing an autopsy in Finland. Unfortunately, the first sign of the cardiac disease these patients were experiencing was sudden cardiac death. As such, it is important that we highlight to the world, and the West in particular, that this is a serious issue. And that seriousness is not only in relation to the patients’ myocardium, which gets thick and the heart becomes enlarged, which is often caused by hypertension and obesity, but also the fact that these people could also die suddenly from these diseases.

How do you hope the research will come to inform future screening programmes for young adults, as well as, perhaps going beyond that, informing healthy eating educational programmes led by the Finnish government or other kinds of policy developments that could go some way to tackling the obesity problem?

We have had discussions with the Finnish Cardiac Society and national Heart Association, which has direct links to the Finnish government, in this context, as well as with the government itself. The problem is well recognised.

At the moment, we do not have that many tools that we can utilise to actually identify those who are at risk. We need to obtain more information and it is important that more people are screened for things like blood pressure or cholesterol levels. We need to garner support for that because this information is vital if we are to save lives. If we continue to wait until someone is already dead before we deduce that the cause of the death was coronary disease, then it is clearly too late. But it is often too late to do anything positive if we do not learn that a patient has a coronary disease until quite late on in their life; if they already have such a condition then it is unlikely to be curable, which means the patient has to manage it for their rest of their lives, often at a cost to the health service. If an emphasis is placed on prevention, however, which I believe it should be, then we can stop this from happening; we can save lives. Much of this will also involve ensuring that the younger generations have a more active interest in their health and wellbeing by educating them on things like lifestyle factors and the role they can play in disease risk.

How significant is the obesity level in Finland at the moment? And is there scope to export your findings and arguments to other countries so that they too can begin to act?

While we have not yet begun any concrete actions to achieve this, but we do collaborate with colleagues in other countries on the issue of sudden cardiac deaths and associated areas. We have a large international consortium within which we are discussing sudden cardiac deaths and how the incidences can be decreased around the world. Through this, we are working to better understand what works in different places and what does not. Essentially, prevention boils down to people living healthier lives.

We do have an obesity problem in Finland; according to the statistics, 75% of over those over 30 years old are technically overweight as they have a BMI of over 25 – indeed, I believe we are number two in the world, behind the USA. And while we do not have that many obese people in Finland – so, those with a BMI of over 30 – the fact that so many people are overweight suggests that obesity will become much more of a problem over the course of the next decade. We are thus at something of a turning point, and while the incidences of young people with coronary disease have been decreasing over the last 20 years or so, the total number of incidences of these diseases, and the associated deaths, is not, with non-ischemic diseases such as those related to obesity actually increasing.

Do you plan to build on this research moving forwards? If so, how? If not, where will your future research priorities lie?

In the future, we want to be able to pinpoint more exact subpopulations before sudden cardiac death occurs. We have identified families with certain genetic variations on myocardial structure genes and are following that up and working to see whether the use of different kind of imaging techniques, such as MRI, will reveal whether they have more myocardial disease than the general population, and we may be able to prevent sudden cardiac deaths in those families.

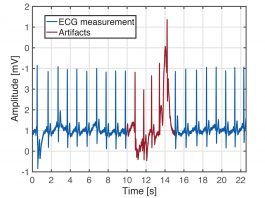

We are also trying to find different clinical markers that these people may have during their lifetime before they die. We have electrocardiograms for around 1,000 of them, which should assist us there.

With regards to the screening programmes that should be made available to the general population, that would perhaps need a two-step approach. First, a subpopulation who has, for example, hypertension or obesity, would need to be identified. An EKG could then be performed and, if something is found, the patients could undergo perhaps a cardiac MRI that would actually find the disease before it causes any severe problems in the myocardium.

That is something we are working on, and we have achieved funding to continue that work over the next five years.

Please note, this article will also appear in the sixth edition of our quarterly publication.