Researchers at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology have discovered that the risk of bird-plane collisions increases significantly during migratory periods.

Bird strikes are random and largely unpredictable events which can have dangerous consequences for aircraft. Although most bird strikes are relatively minor in terms of the damage they cause to aircrafts, large flocks of birds can result in multiple strikes and therefore pose a significant threat to the safety of a plane and its passengers. A notable example of this is the 2009 US Airways Flight 1549, which was navigated to safety in the Hudson River after the aircraft’s engine lost all power following a strike by a flock of birds. To avoid incidents such as these, ongoing research into bird flight patterns, including migration, is of vital importance.

In an effort to strengthen knowledge surrounding bird migratory patterns and strikes, scientists from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology carried out an analysis of bird strike data from three New York City area airports from 2013 to 2018. The study, led by Cecilia Nilsson, set out to identify patterns in bird strike data and determined that the risk of planes colliding with birds increases by up to 400% during periods of migration. The findings from the study have since been published in the Journal of Applied Ecology.

To discover more about the study and the potential applications for future research and innovations to prevent bird strikes, Innovation News Network spoke to Cecilia Nilsson, former Rose Postdoctoral Fellow at the Cornell Lab and lead author of the study. Cecilia is now a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Can you explain the general overview of the study? What was the aim of the investigation, why was it necessary, and how did you carry it out?

As biologists working on bird migration, we spend a lot of time studying and mapping movement patterns of birds. Through discussions with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ), we decided to see if there was a way in which we could utilise ecological knowledge and methods to inform bird strike risk at airports.

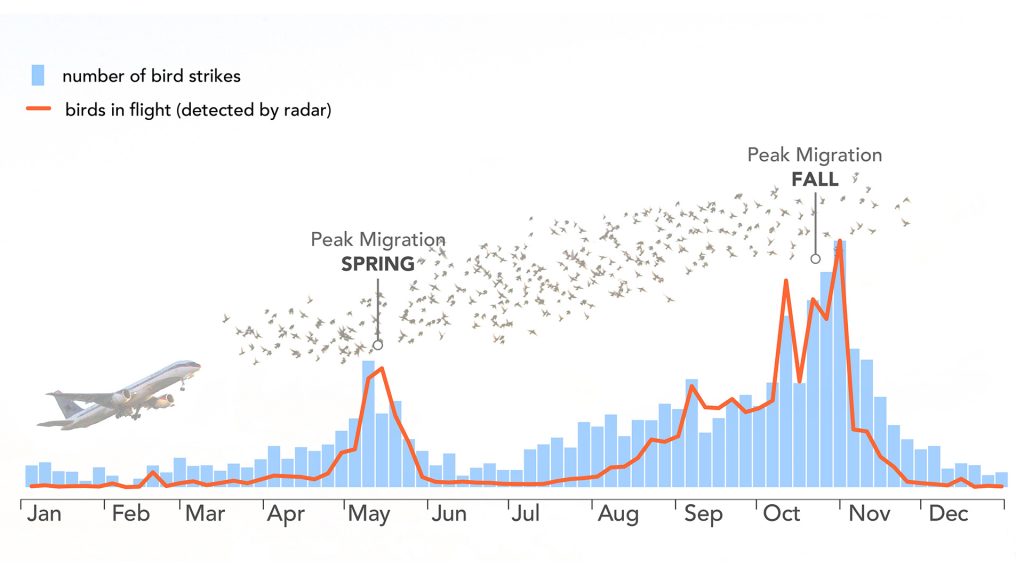

We used weather surveillance radars from two nearby stations to learn when migration was the most intense at the airports studied. When we first retrieved bird strike data from the PANYNJ for the airports of Newark, LaGuardia, and John F. Kennedy, we quickly determined that the number of bird strikes that occurred at the airports followed the seasonal patterns we knew from bird migration studies. We found that many more strikes happened during the movement periods in spring and autumn.

This led us to investigate how well bird movement data from local weather radars and species observations from the Lab’s eBird observation programme correlated with not only the number of bird strikes, but also the severity of the strikes. The species information was important because most bird strikes actually cause very little or even no damage, but collisions with larger bird species, such as geese, are more likely to damage the aircraft.

What were the main findings of the study?

We saw that periods of high movements corresponded to periods of high numbers of bird strikes at the airports, and, by using species observation data, we could also show that, when large species of birds were present in the region, the risk of a damaging strike occurring was higher. We found that 90% of the strikes involved a migratory species, with our model predicting that the risk for damaging strikes during periods with very high migration intensity increases by as much as 400% to 700%.

We noted high hazard scores in species including Canada geese, great blue herons, mallards, and turkey vultures. Our analysis found that Canada geese were most likely to cause damage. The greatest number of bird strikes at the three airports involved the American robin.

How could this research help in the implementation of measures to reduce the number of strikes in the future?

We hope that this study will highlight the possibilities of using bird migration data to understand seasonal changes in bird strike occurrence at airports. Species composition and the start and end of migration movement periods is unique for each region, so using bird movement data and species occurrence from the region, as presented in our study, could help airport managers to plan mitigation actions that are fine-tuned to their location.

Are there any limitations of the study to consider?

The weather radar data and eBird data used in our study describe the species occurring and the amount of movement occurring in the region surrounding the airports, and is therefore useful for planning of actions, setting up standard warnings, etc. However, the data used here cannot be used for real-time warnings of individual birds occurring in airspace of the airport or collision warnings. Another thing to note is that current developments and fine-tuning of both the way we process weather radar data and new data products from eBird will also increase the accuracy of the data, which could hopefully lead to even better descriptions of the bird movement patterns at airport locations.

Although you are no longer with Cornell, do you plan to look at bird strikes further in any of your future research?

The use of weather radar data to track bird movements is increasing worldwide, and so are citizen science programmes reporting bird species observations. It is therefore increasingly possible to obtain similar for other airports, and I hope to be able to look into this for some European airports in the near future.

Cecilia Nilsson

Former Rose Postdoctoral Fellow

Cornell Lab of Ornithology

www.birds.cornell.edu/home

https://www.linkedin.com/company/cornell-lab-of-ornithology/

https://twitter.com/CornellBirds

Please note, this article will also appear in the eighth edition of our quarterly publication.