Cornish Lithium’s Alistair Salisbury discusses the utilisation of hyperspectral and drone data to enhance sustainable exploration for lithium in Cornwall.

The World Bank predicts a dramatic rise in the demand for technology and battery metals, including lithium. It is forecasting demand to increase by 500% from 2017 levels by 2050. To meet these ever-growing raw material requirements for clean technologies, it has become imperative to expand exploration for commodities such as lithium to new unconventional targets.

Some of these new targets include lithium enriched geothermal waters circulating at depth in Cornwall. Cornish Lithium’s project in the UK differs from those seen elsewhere on the globe. Brine projects, such as those found in the Atacama Desert in South America, require evaporation ponds that utilise vast amounts of water, in an area where water resources are incredibly scarce, and need huge areas of land. Direct Lithium Extraction (“DLE”) technologies, such as those being trialled by Cornish Lithium, can provide the same lithium compounds, but use a fraction of the resources and have much smaller surface footprints. A domestic lithium resource for the UK will reduce the carbon footprint of supply chains, as well as encouraging sustainable extraction and a greener approach to lithium mining.

A Holistic Approach

A holistic approach to raw material exploration and extraction must be taken to ensure the drive towards the green revolution fully encompasses sustainability and Environmental, Social and Governance (“ESG”) protocols. In practical terms, this means that the most efficient and least energy intensive route to delivering a mineral resource must be sought. Providing the raw materials to enable this transition towards clean technologies (wind turbines, photovoltaic solar panels, energy storage) requires exploration, that leads to quantification which in turn leads to a mineral resource.

Quantification usually involves drilling and extensive exploratory drilling programmes can be mitigated by using innovative exploration techniques that are more efficient, saving time and money throughout project development. The requirement to expedite these resources of technology metals has become even more imperative to meet the demand of the energy transition and meet the required reduction in greenhouse gas emissions to limit global temperature rises to 1.5C by 2050 (IPCC, 2018). This means substantially larger amounts of renewable technologies will need to be manufactured to keep to these emissions targets.

Innovation in Sustainable Exploration

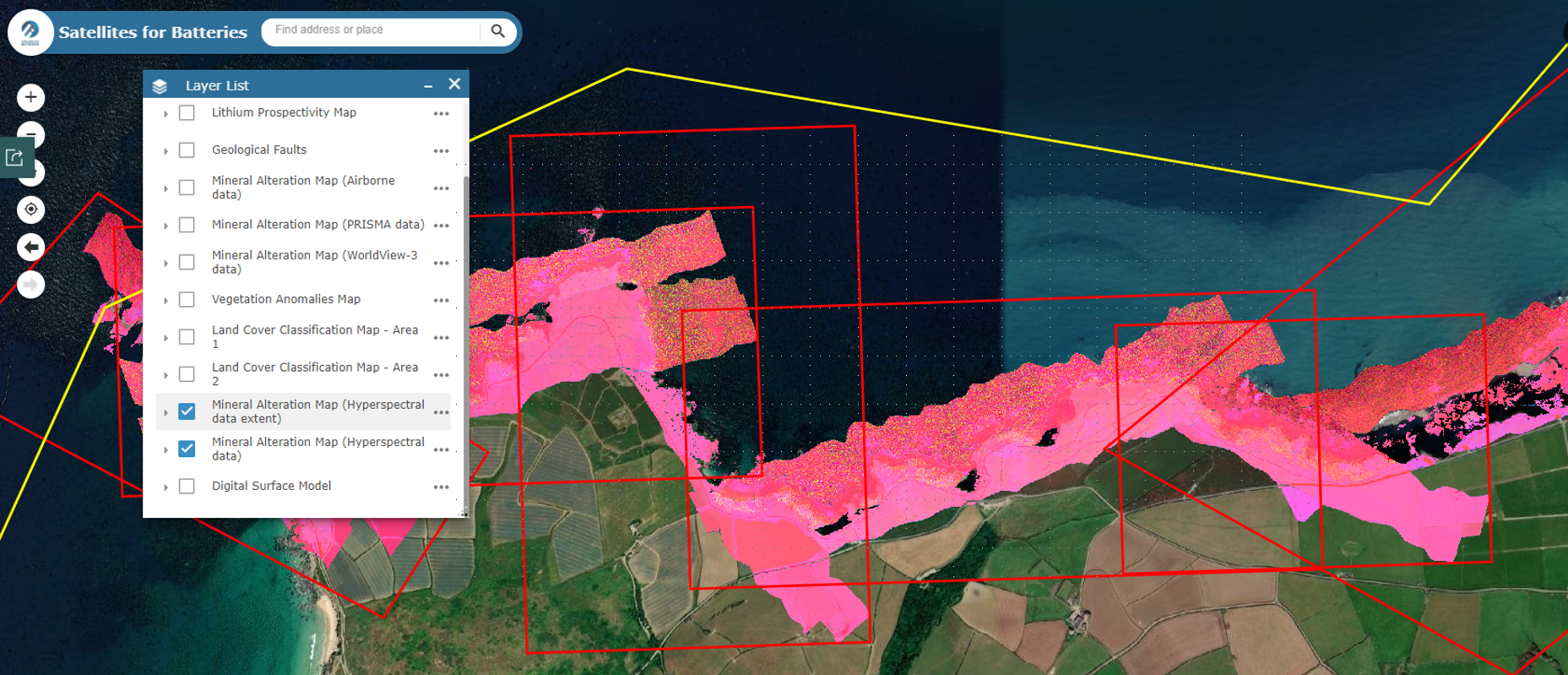

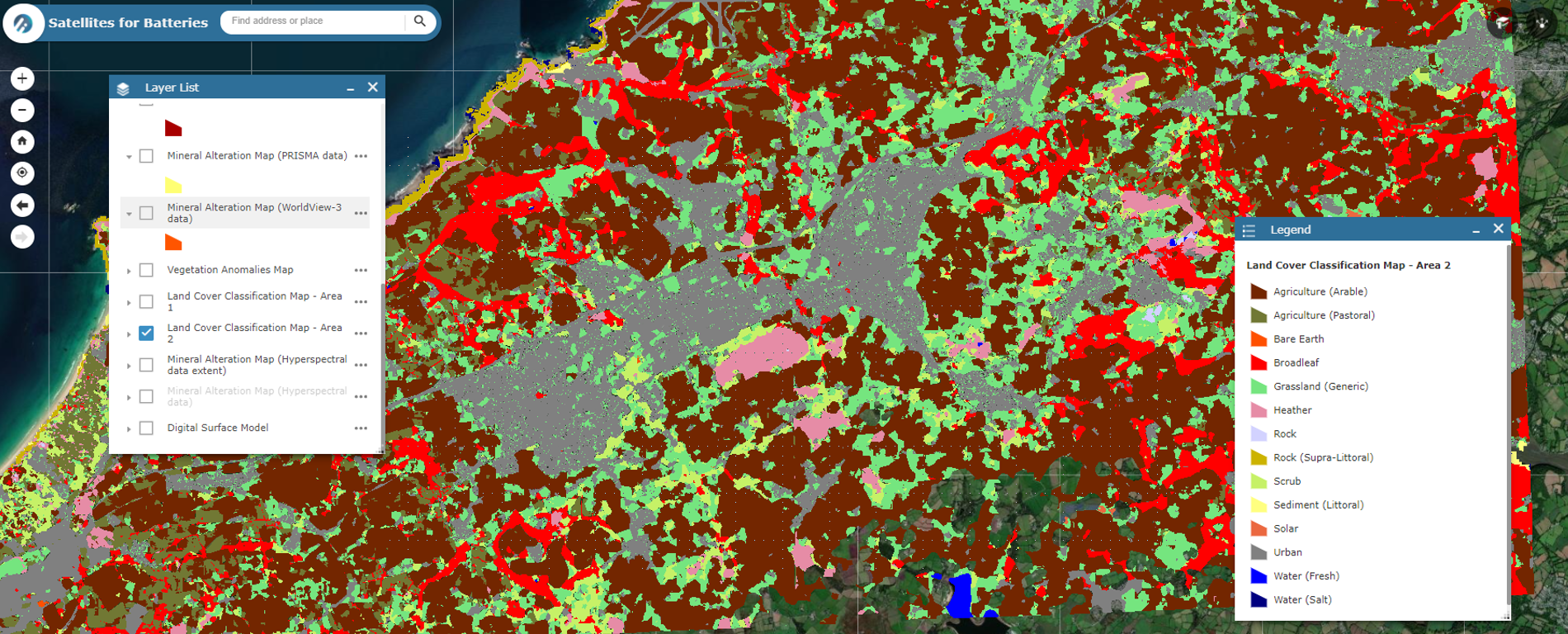

Since the inception of the company in 2016, Cornish Lithium has been using innovative methods that take sustainable exploration in the UK to new frontiers. Projects partnering with earth observation specialists utilising satellite imagery to hone in on prospective targets for lithium in Cornwall and de-risking the exploration effort has been undertaken since the Lithium 1 project in 2018.

Since this initial study in 2018 Cornish Lithium have expanded their Earth Observation (“EO”) and Remote Sensing (“RS”) portfolio to adapt to Cornish geology and to their expanding exploration programme.

3D Drone Mapping and Hyperspectral Imaging

A key premise when wanting to understand the distribution of lithium-enriched geothermal waters is being able to accurately map alteration assemblages and fracture intensity surrounding fluid pathways. This can be done by using conventional mapping and analytical techniques. However, this can be time consuming and requires lengthy laboratory analyses to verify findings. Field areas in Cornwall can be challenging, and by utilising remote sensing technologies this can be done from a safe distance to make digital twins of the outcrop that be analysed from the office. Follow-up field verification can then be planned efficiently and with minimal risk to the field geologist.

Hyperspectral mapping was undertaken using a hyperspectral camera mounted on an aircraft capable of flying at low altitude. This captured data in the electromagnetic spectrum from the visible to the short-wave infrared wavelengths. Minerals that have surface exposure on the ground reflect light at different intensities and different wavelengths depending on their crystal structure and their chemical composition. These spectra are collected by the hyperspectral imaging camera and processed by specialist software. Using careful “fingerprinting” and spectral analyses of mineral assemblages, the magnitude of geothermal alteration that surrounds known fluid pathways can be assessed.

3D modelling is a tried and tested exercise for geologists. However, this usually involves careful modelling from expensive geophysical data or by extrapolating between many boreholes drilled deep into the ground; both involve high capital expenditure.

At Cornish Lithium one of the ways that 3D modelling is performed is by using photogrammetry. These photogrammetric surveys are carried out on coastal cliffs where rock exposure is good. These can be hundreds of metres across and tens of metres high. Thousands of photographs are taken using drone mounted cameras, flying automated flight paths for site overviews and manual flights for cliff close-ups and high-resolution surveying. This is especially useful for fracture mapping.

These photographs are then compiled using Structure from Motion (“SfM”) software and photo-realistic 3D models are generated. The 3D models are then digitised to carefully pick out fractures and geological units that are often missed or cannot be accessed when physically at the site in question. These models can then be extended and applied in-land by digitising and modelling historic mine records to further enhance our understanding of the subsurface. Doing this gives a much better understanding of the geological tectonic regime of the outcrop which can then be used to infer fracture intensity which in turn helps improve our estimate on reservoir quality for these geothermal brines.

These photographs are then compiled using Structure from Motion (“SfM”) software and photo-realistic 3D models are generated. The 3D models are then digitised to carefully pick out fractures and geological units that are often missed or cannot be accessed when physically at the site in question. These models can then be extended and applied in-land by digitising and modelling historic mine records to further enhance our understanding of the subsurface. Doing this gives a much better understanding of the geological tectonic regime of the outcrop which can then be used to infer fracture intensity which in turn helps improve our estimate on reservoir quality for these geothermal brines.

Combining Remote Sensing Studies

By combining photogrammetric drone surveys and hyperspectral imaging technologies Cornish Lithium has showcased the power of remote sensing for exploration for lithium in geothermal waters. Utilising this, and the plethora of historic mining data in the Cornish Lithium archive, provides an invaluable resource for accurately generating subsurface geological models for future exploration programmes further de-risking and decarbonising site assessment.