Environmental scientists from St. Edward’s University discuss how paying landowners to protect trees could help preserve tropical forests.

Tropical forests are home to half of the species on earth, while providing essential global services such as regulating climate, purifying air and water, and serving as a source of resources for local communities. However, most tropical forests exist in the developing world where they are threatened by population growth, development pressures, urban sprawl and legal and illegal exploitation and conversion. As a result, half of earth’s tropical forests have been lost to deforestation over the past fifty years.

Efforts to preserve forests and other valuable ecosystems have historically focused on creating national parks and other protected areas that restrict human activities within their boundaries. However, in the Global South, where citizens rely heavily on natural resources for subsistence, expanding protected areas is frequently hindered by lack of political support and local animosity. Rapid population growth and expanding urban areas have also greatly reduced the amount of available land to be protected. Moreover, the lack of effective enforcement has caused many protected areas to resemble ‘paper parks’ in which resource exploitation continues despite their nominally protected status.

Recognising this need to expand conservation policies beyond the protected area focus, in 1997 Costa Rica pioneered an innovative incentive program that pays landowners to maintain forests on private lands. The Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES in English or PSA in Spanish) programme provides an annual stipend to landowners who agree to maintain their forested land.

Most participants enrol to protect their existing forests, but reforestation, sustainable management and restoration activities are also eligible.

Paying Landowners in Costa Rica

Costa Rica’s tropical forests and the biodiversity they contain are globally renowned. With only 0.3% of the earth’s landmass, the nation is home to 5% of all known species including over 100 species of bats and 900 species of birds – more than in the United States with an area almost 200 times larger. Innovative policies such as PES and its goal of becoming the first carbon neutral nation, have led the small Central American nation to be recognised as a global leader in sustainable development and a major ecotourism destination.

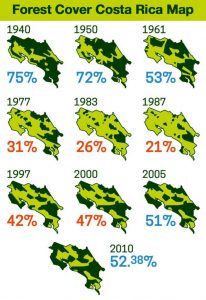

However, as recently as the 1980s, Costa Rica resembled many developing nations in experiencing widespread deforestation with forest cover decreasing from 70% in 1950 to less than 25% by the late 1980s. In the 1990s, recognising that the country’s natural wealth could be a means of economic development, President Jose Figueras adopted sustainable development as national policy. The 1996 Forestry Law subsequently provided the legal basis for the PES program. The law incorporated traditional regulatory elements such as prohibiting forest conversion while also legally recognising the value of ecosystem services provided by forests such as carbon sequestration and biodiversity protection. Traditionally, nations have managed forests primarily for timber production. By legally recognising the economic and social values of the ecosystem services provided by forests, this law provided a rationale for the government paying for these services.

This direct payment approach represented a significant innovation in conservation policies by providing private landowners an economic incentive to conserve their forest. Prior to PES, the primary way landowners could receive economic benefits from their forested land was to cut it down to sell the timber or transform into cropland, pasture or subdivisions.

Reversing Deforestation

Although it’s difficult for the PES payments to compete with the potential earnings from conversion to these alternative land use strategies (at least in the short term as tropical forest soils are generally unsuited for sustained intensive agriculture), they can provide an important supplement to household incomes for landowners interested in keeping their land forested. Importantly as well, the payments emphasise that the nation’s forests are of national importance and thus worth paying for. Since the program’s inception, over 10,000 farmers have been paid to preserve nearly one million hectares of forest. Costa Rica’s forest cover has increased to over 50% of its land area making it the only nation in the world to significantly increase its tropical forest cover.

Due largely to Costa Rica’s experience, direct payment programs have spread throughout the developing world. Mexico, Ecuador, Bolivia, Vietnam, Mozambique and Uganda are some of the nations that have adopted similar direct payment programs based on the Costa Rican model in the attempt to replicate their success at reversing deforestation and increasing forest cover.

Evaluating PES

This global expansion has led PES to be one of the most widely researched conservation policy strategies of the last decade. These studies have produced inconclusive findings regarding the effectiveness of PES at conserving tropical forests as well as providing sufficient income to encourage landowners to change their behaviour. In the Costa Rica case, landowners have been paid based on the size of their parcels, rather than its ecological value or risk of being cleared. Moreover, large landowners are disproportionately represented in the program. While they be giving up potential income by maintaining their forest, they are unlikely to be relying on the forest for subsistence or potentially have the desire to convert their forest to other uses. Many larger landowners have also started ecotourism operations, providing another means of receiving income from forest protection.

Thus, it can be difficult to determine the extent that PES has been responsible for Costa Rica’s remarkable increase in forest cover. PES has also been accompanied by the broader national policy of sustainability including mandatory environmental education, promotion of ecotourism as a development strategy and marketing the nation’s natural resources and sustainability as a global brand. As demonstrated by the fact that forest cover had begun increasing in the decade prior to the implementation of PES, these other policies have likely also been a factor in altering citizen behaviour towards forest protection.

These complicating factors have led to scholars revising their research methods and conservation planners to revise their PES programs. In a second stage of PES research, scholars are beginning to employ remote sensing and experimental controls to try and isolate the impacts of PES from these other potential factors influencing individual decisions to cut or maintain the forest. Overall, these controlled studies indicate that PES has been responsible for a modest reduction in deforestation levels where they have been adopted. Costa Rica has subsequently revised its program based on these evaluations, including targeting distributions towards more small landowners and areas of greatest ecological value.

Although protected areas will continue to be an important forest conservation tool, by encouraging conservation on private lands, economic incentive programs such as PES will likely continue to expand their role in efforts to preserve tropical forests and other valuable natural areas.