Fusion reactors hold great promise as a future energy source, but can we design materials to withstand the power of such an artificial star? Specialised facilities built at the Dutch research institute DIFFER show how a small lab can make a big splash in fusion science.

“Ready for the next shot?” Scientists and engineers wait as a clock on the overhead status screen counts down the seconds. Then, a sudden flash of bright light from a computer monitor: the onboard camera, quickly stepping down to resolve a blinding glare into a beam of glowing hot gas.

We are in the control room of the Dutch research facility Magnum-PSI, which has just struck a sample of tungsten metal with a beam of blazing plasma of tens of thousands of degrees Celsius. The hail of fast, charged particles bombards each square metre of its target material with tens of megawatts of heat. Like being at the surface of the Sun, for hours at a time.

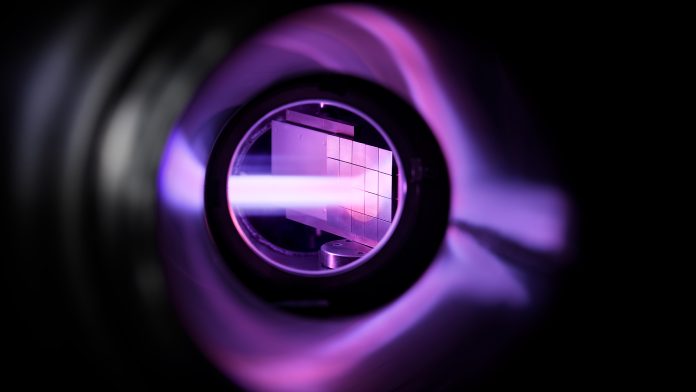

DIFFER’s Ion Beam Facility delivers fast ion particles to up to seven different experiments in the building to study materials’ evolution

At Magnum-PSI, designers of future fusion power plants can test materials for their tokamaks and stellarators. Those reactors will need to stand up to the task of producing energy from the same process that powers the stars. Magnum-PSI’s 15m-long assembly of stainless-steel vacuum chambers is just one of the large machines that the Dutch Institute for Fundamental Energy Research (DIFFER) uses to put fusion materials to the test.

Key question

Visitors to DIFFER are often surprised to learn that the Centre for Fusion Research does not have a fusion reactor of its own, explained Hans van Eck, Head of DIFFER’s facilities and instrumentation. Instead, the institute decided decades ago to specialise in answering a question that each and every participant in the global race towards fusion energy has to face: What happens to materials during their lifetime in a fusion reactor? To answer that question, DIFFER built dedicated machines that mimic the conditions where a fusion plasma is touching its reactor wall.

Van Eck said: “Modern tokamaks and stellarators are taller than our entire building. Add the supporting facilities for heating, cooling, instrumentation and the electrical yard, and the site would fill most of the university campus. There is no way we could operate anything such as ITER and other public or private reactors here.”

DIFFER’s specialised facilities instead take a unique position in between fusion reactors and the table-top setups operated by smaller university groups. “Our facilities answer fusion-relevant questions at a level of detail you cannot manage anywhere else,” continued Van Eck.

Indeed, a 2024 review of all the fusion-relevant experimental facilities in Europe by the EUROfusion consortium designated the DIFFER hardware as “indispensable” – the highest possible accolade.

World record

For an example of how DIFFER contributes to the world of fusion, take the metal tungsten. With its 3,400°C melting point, it is the current material of choice to protect the insides of fusion reactors. The ITER project for instance, built by a global consortium of researchers in the south of France, announced in 2024 that it would build its entire inside wall out of tungsten.

Properly cooled, tungsten can handle the incredible heat flow of fusion. But expectations are that years in contact with the ITER plasma will still cause damage like embrittlement. By how much? The answer impacts repair schedules, costs and planned maintenance for future power plants. The Magnum-PSI facility is the only device in the world that can already expose materials to conditions the same as expected in ITER, or even the more intense conditions expected in the tokamaks designed by private companies.

In 2018, the Magnum-PSI team even set a world record by exposing tungsten samples to as much plasma in 18 hours as they would face during an entire year of high-power operation in ITER. The metal held up well, making ITER confident that its materials choice is the right one. A prime example of how smart specialisation lets a small research institute have global impact, Hans van Eck believes.

Disentangle

Thomas Morgan leads DIFFER research on the interplay of plasmas and wall materials. He explained why the institute’s facilities can give a much clearer picture of materials degradation than modern fusion reactors themselves.

DIFFER’s Magnum-PSI facility creates plasma conditions as harsh as at the surface of the Sun to test materials for the exhaust of fusion power plants

Morgan said: “Large machines can only open up their vacuum vessels and retrieve pieces of wall material after completing scientific campaigns of dozens to hundreds of shots, each with different conditions.” That compound mix of always-changing conditions makes reconstructing how and why a material evolved almost impossible, the physicist concluded.

In Magnum-PSI, a long robot arm can retract a sample to an analysis chamber after a shot to study its response to just one changed plasma parameter, like the temperature or particle impact energy. And in the institute’s new facilities, technicians and researchers can even study those effects during plasma exposure.

The future is a live view

Talk to materials scientist Beata Tyburska-Pueschel, and the performance of Magnum-PSI will seem like yesterday’s news. As head of a specialised particle accelerator in the hall next to the institute’s workhorse plasma device, she runs DIFFER’s Ion Beam Facility (IBF).

The IBF can study the deep structure of a material like cracks, cavities, or defects in the perfect atomic lattice of a material by bouncing a stream of fast particles off the sample. Crank up the energy, and the machine can even mimic the kind of damage done by the impact of neutron particles from the fusion reaction.

Tyburska-Pueschel explained: “The true game-changer has been that we can now do all this during plasma exposure, not just before and after.”

By connecting the IBF to a smaller version of Magnum-PSI called UPP, DIFFER can get a live view of how a material changes from second to second while exposed to hot plasma. That capability is unique in the world, explained Tyburska-Pueschel, and one that opens up a whole new way of studying how different processes inside a reactor modify their wall materials.

Tyburska-Pueschel’s favourite example is two competing processes inside a fusion reactor wall. On the one hand, fast neutrons from the fusion reaction create defects in the material, like microscopic cracks and cavities. On the other hand, hydrogen isotopes from the fusion fuel seep into the metal and fill those vacancies. Do those processes influence each other?

She continued: “If you first create defects in one experimental setup and then load the material with hydrogen in another machine, you will never see how the hydrogen takes up space in the defects and prevents them from self-healing as the atoms move around from the bombardment. We can now study that synergy as it happens.”

“Now they want more”

From 500 hours of IBF beam-time and five users in 2021, the Ion Beam Facility has grown to 3,000 beam-hours and 20 different users in 2025. That is about the limit of what is possible in a regular working year, taking shutdowns for maintenance and upgrades into account, but users inside and outside the institute are asking for even more experimental time.

“Our users have gotten that first taste of what the IBF can do and now they want more”, said Tyburska-Pueschel.

The machine has even taken steps outside of the world of fusion, with experiments for DIFFER’s department on electrochemical water splitting and for a consortium investigating materials issues in molten salt reactors.

“Right now, I am fully booked, so we might have to plan extra shifts or apply for grants to add a second accelerator.”

Self-healing

One power user of the DIFFER facilities for fusion materials is the institute’s plasma materials physicist, Thomas Morgan. After initial experiments in Magnum-PSI, he has now won a grant from the Dutch science funding agency NWO to further study a dark horse in fusion materials together with colleagues from nearby Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e). The topic: self-healing layers of liquid metal that protect the insides of a fusion reactor.

The idea is as mind-boggling as it is simple. Designed just right, a cover of liquid metal flowing over and through an underlying mesh would be able to repair itself from any plasma damage. The physicist and his team have built setups at DIFFER and at TU/e to study the entire lifecycle of such components.

Those facilities range from a 3D printer to create the ideal supporting mesh, to setups that can expose the component to plasma and test the best metal for the job. There is even a dedicated machine in preparation to check how hydrogen isotopes from the fusion fuel might get trapped in the liquid metal, and whether they escape in a steady flow or in big, disruptive bubbles.

Long-term relevance

Asked about what it takes to have research facilities like DIFFER’s, Hans van Eck is clear. It takes the proverbial village to design, build, maintain and operate the institute’s mid-scale facilities. In fact, his technical support department makes up a quarter of the entire institute. That includes the in-house design office and mechanical workshop, the electronics and software engineers, and the dedicated operators. Quite the difference from university groups with one technical engineer per research group of ten scientists.

“Facilities take courage to invest in”, stated Van Eck. “I would say that this is only possible at an institute with long-term funding stability.”

Once built, the facilities in their experimental halls last for years of continuous upgrades and improvements.

Asked where the DIFFER facilities will go in the future, Beata Tyburska-Pueschel explained that the machines should keep improving to stay at the forefront of science. She said: “My dream is for the Ion Beam Facility to go autonomous. Right now it can run through the night on pre-programmed instructions; with AI support, it should be possible for the system itself to determine what interesting features in an analysis are and what kinds of measurements it should make to get insightful data for our users. Come back in a few years and I hope to have that available.”

Please note, this article will also appear in the 22nd edition of our quarterly publication.