The first batch of data released by the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) has identified around two million interstellar objects.

The Universe continuously expands due to a mysterious force known as dark energy. The DESI survey aims to unravel the enigmatic nature of dark energy by mapping over 40 million galaxies, quasars, and stars.

Performed using the Mayall 4-meter telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory, the DESI project has now released its first set of data, which contains around two million objects for researchers to explore – a significant milestone for understanding the nature of the Universe.

Nathalie Palanque-Delabrouille, co-spokesperson for DESI and a scientist at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, explained: “The fact that DESI works so well and that the amount of science-grade data it took during survey validation is comparable to previously completed sky surveys, is a monumental achievement.

“This milestone shows that DESI is a unique spectroscopic factory whose data will not only allow the study of dark energy but will also be used by the whole scientific community to address other topics, such as dark matter, gravitational lensing, and galactic morphology.”

How does DESI work?

DESI employs 5,000 robotic positioners to operate optical fibres that capture light from objects in space – even some millions or billions of light-years away.

This makes DESI the most powerful multi-object survey spectrograph globally and can measure light from over 100,000 galaxies in just one night. This helps researchers build a cosmic map of the Universe and understand dark energy.

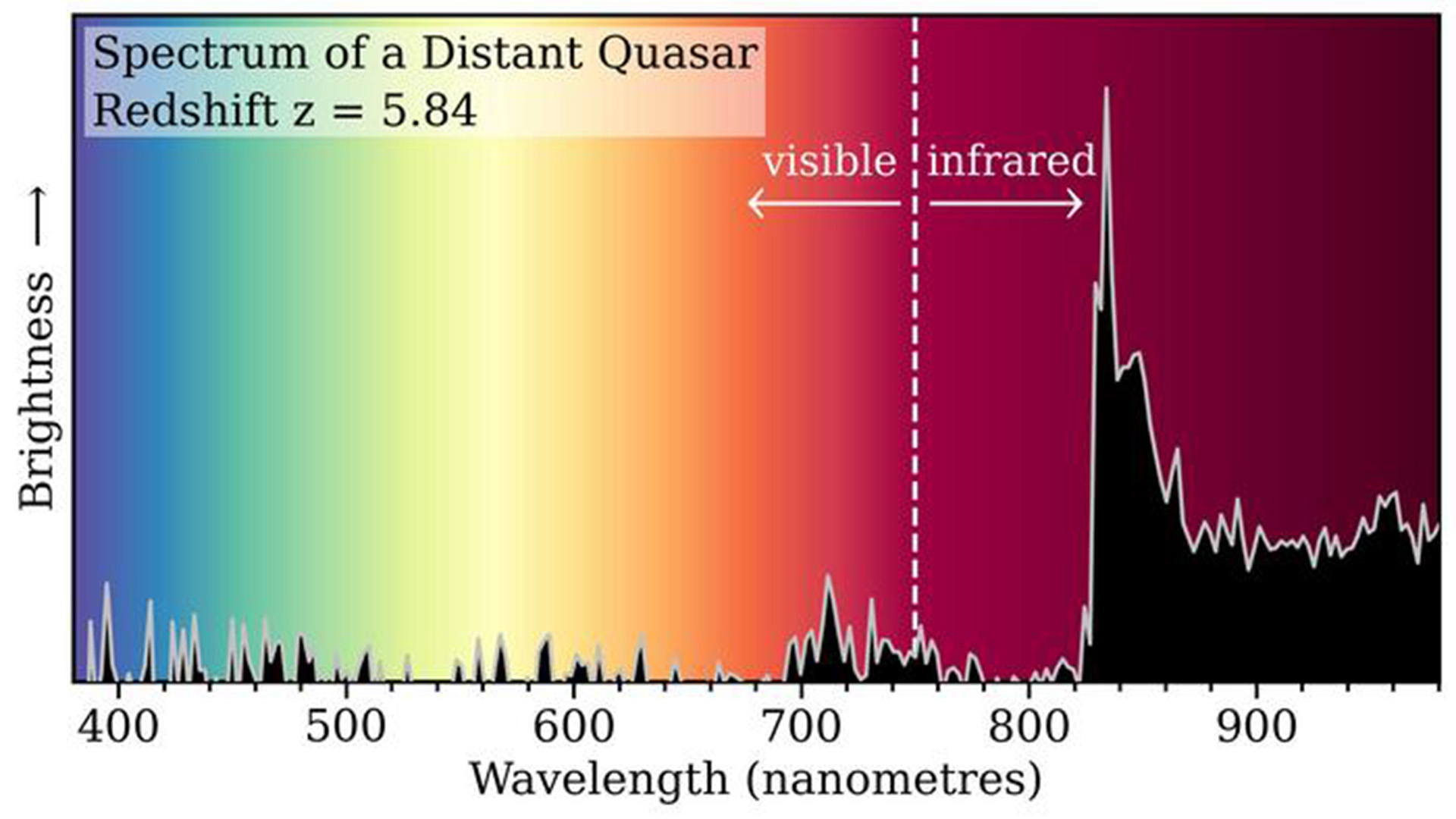

As the Universe expands, it stretches the wavelength of light – a phenomenon known as redshift. The further a galaxy is away, the larger the redshift is.

DESI expertly collects redshifts to understand what dark energy is and how it has evolved throughout the history of the Universe.

In addition to dark energy, DESI data includes images of some famous areas of the sky, such as the Hubble Deep Field, which will be essential in future astronomical studies.

Stephen Bailey, a scientist at Berkeley Lab who leads data management for DESI, commented: “There are some well-trodden spots where we’ve drilled down into the sky.

“We’ve taken valuable spectroscopic images in areas that are of interest to the rest of the community, and we’re hoping that other people will take this data and do additional science with it.”

What does the data reveal about dark energy?

DESI has made two groundbreaking discoveries – finding evidence of a mass migration of stars into the Andromeda galaxy, and extremely distant quasars.

Anthony Kremin, a postdoctoral researcher at Berkeley Lab who led the data processing, explained: “People have looked at that data and discovered very high redshift quasars, which are still so rare that basically, any discovery of them is useful.

“Those high-redshift quasars are usually found with very large telescopes, so the fact that DESI – a smaller, 4-meter survey instrument – could compete with those larger, dedicated observatories was an achievement we are pretty proud of and demonstrates the exceptional throughput of the instrument.”

Validating the survey was also an opportunity to test the method of transforming raw data from DESI’s ten spectrometers into useful information, as the spectrometers split a galaxy’s light into a range of colours.

“If you looked at them, the images coming directly from the camera would look like nonsense – like lines on a weird, fuzzy image,” said Laurie Stephey, a data architect at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), the supercomputer that processes DESI’s data.

“The magic happens in the processing and the software being able to decode the data. It’s exciting that we have the technology to make that data accessible to the research community and that we can support this big question of ‘what is dark energy?’”

What does the future hold for the project?

DESI is currently only two years into its five-year run – with plenty of data left to collect. It is estimated that DESI will obtain more than 40 million redshifts and has already catalogued over 26 million astronomical objects – around one million per month.

In the coming years, DESI will potentially have acquired enough data to solve the mystery of dark energy.