Nova Scotia, a linchpin in Canada’s critical mineral supply chain, navigates a historic legacy to spearhead exploration and mining, aligning with a low-carbon future.

The province of Nova Scotia has a key role in Canada’s critical mineral supply chain – through exploration, mining, refining, manufacturing, and recycling – as the province moves toward a low-carbon economy and a goal of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Nova Scotia’s exploration and mining industry employs more than 3,200 people from a population of just over one million and contributes approximately $400m to the province’s economy annually. We have a highly educated workforce and an excellent service/supply sector needed for a flourishing exploration and mining industry here. Nova Scotia has many deep-water ports that are naturally ice-free and can be navigated year-round.

Nova Scotia as a mining province

Nova Scotia has a strong history as a gold, coal, and gypsum producer, among other commodities, with mining operations occurring at least as far back as 1720. Nova Scotia had many historical mines for what are now called critical minerals (copper, zinc, manganese, etc.), and these early mines show that the province has a diverse mineral endowment that can be successfully explored for new critical mineral deposits, contributing to the global supply of these minerals.

It has incredible potential for hard rock lithium mining, with a current major focus by exploration companies on the South Mountain Batholith in the southwest part of the province, the largest composite batholith exposed in the Appalachians.

Nova Scotia will be releasing its Critical Mineral Strategy soon. This strategy is not intended to limit exploration or mining of other minerals, but rather to focus resources, both human and financial, on the minerals required to meet net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Nova Scotia has used four criteria to develop its critical minerals list:

• Potential for exploration and identification of a mineral resource within the province;

• Requirements for Nova Scotia to reach its emission reduction targets, including 80% of energy produced from a renewable source by 2030, and net-zero emissions by 2050;

• Current and/or expected supply and demand imbalance on a global scale; and

• Likelihood of presenting a strategic opportunity for the province.

Nova Scotia considers 16 minerals to be critical, including antimony, cobalt, copper, graphite, germanium, gallium, indium, lithium, manganese, molybdenum, niobium, rare earth elements (REEs), tantalum, tin, tungsten, and zinc.

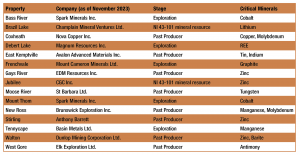

Upstream critical mineral projects in Nova Scotia

Five of these properties will be discussed in more detail below, as they highlight the diverse geology and the significant potential of finding and developing critical mineral projects in Nova Scotia.

Brazil Lake spodumene-bearing pegmatites

The Brazil Lake lithium project is approximately 25km north-northeast of Yarmouth in southern Nova Scotia and approximately 300km southwest of Halifax. Meta-sedimentary and meta-volcanic rocks of the White Rock Formation host the highly evolved, spodumene-bearing pegmatites. Mineralisation of the Brazil Lake pegmatites is paragenetically similar to the mineral sequence typically seen in peraluminous granites. Sampling results show locally anomalous Li, Rb, Sn, and Be levels. These correspond, respectively, with dominant host minerals spodumene, potassium feldspar, minor accessory cassiterite, and beryl, all identified in drill core and outcrop. Regional exploration activities indicate additional mineralisation may be present and are yet to be discovered in this region of Nova Scotia.

The Brazil Lake lithium project mineral resource estimate, as of 6 August 2023, has been reported following JORC (2023) guidelines as 10.01 MT @ 1.20 Li2O at a cutoff grade of 0.33% Li2O. This mineral resource estimate results from combining three spodumene-bearing pegmatites: the Army Road, North, and South sites.

The Mineral Resource Estimate incorporates data from 167 diamond-drill holes, with 33,311m of core.

Coxheath early- to mid-stage Cu-Mo-Au porphyry-epithermal system

Nova Copper Inc. is a privately held junior mining company that has 100% control and ownership and is actively exploring and defining the Beechmont 30km2 genetically linked porphyry-epithermal system property divided into three separate contiguous claim groups, including the historical Coxheath deposit. This property is near Sydney, which has a year-round, ice-free, deep-water port.

There is a mix of greenfield and brownfield sites with multiple mineralised zones related to a linked copper–gold–molybdenum polymetallic porphyry-epithermal system. The deposit occurs within a late Precambrian, medium- to fine-grained hornblende diorite pluton that intrudes a volcanic covering of basalt and basaltic andesite.

There are 175 drillholes / 30,000m of historic drilling, and extensive geoscience data, including airborne surveys, all digitised.

Scotia Mine (zinc/lead/gypsum)

The Scotia Mine consists of a built and permitted mine and mill, 100% owned by Scotia Mine Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of EDM Resources Inc. (EDM). Scotia Mine is approximately 60km northeast of Halifax, near Halifax International Airport.

The geology of the area is dominated by Carboniferous sediments of the Windsor Group, which overlie Horton Group sedimentary rocks and meta-sedimentary rocks of the Meguma Supergroup. The mineralised rock (Gays River Formation) is a dolomitised carbonate reef, occurring as a basal breccia/conglomerate or directly in contact with basement rocks of a paleotopographic high. Mineralisation consists of massive and/or disseminated ore. Gays River is considered to be a Mississippi Valley-type deposit.

Zinc and lead were discovered in the Gays River area in 1972. The Scotia Mine was operated in the 1980s and in 2008. In 2011, EDM Resources (previously called Selwyn Resources Limited) purchased the mine and all its assets.

The Scotia Mine mineral reserves are classified as either proven or probable, with total reserves of 13.66 million tonnes with a zinc equivalent grade of 3.09% (2021 Updated Pre-Feasibility Study NI 43-101 Technical Report). The Scotia Mine has robust economics with a pre-tax NPV (8%) of $174m, IRR of 69%, and forecast annual cash flows of $13-$41m per year over a long mine life of 14 years.

The Scotia Mine is waiting on a permit from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans and is expected to commence commercial production in 2025.

East Kemptville tin-indium property

Avalon Advanced Materials Inc. is 100% owned by the East Kemptville Tin-Indium Project, located approximately 45km northeast of Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, near the former East Kemptville Tin Mine. The property is approximately 300km by road from Halifax.

The East Kemptville Tin-Indium Project is located within the Cambrian-Ordovician Meguma Terrane, a succession of interbedded, metasedimentary rocks intruded by Devonian granites of the South Mountain Batholith, the largest composite batholith exposed in the Appalachians.

The deposit is a greisen-hosted tin-copper-zinc-silver-indium deposit, with the alteration and mineralisation predominantly altering the local leucogranite of the South Mountain Batholith, in contact with the Meguma Supergroup metasediments.

The past-producing East Kemptville Tin Mine had a historical resource of 56.1 MT of 0.163% Sn (Rio Algom Limited, 1983), and is presently in re-development. A preliminary economic assessment (NI 43-101) was released in 2018 by Avalon Advanced Materials Inc. This re-development plan is mainly an environmental remediation project that involves the processing of the 5.87 MT stockpile of previously mined oxidised, low-grade mineralisation, supplemented by the selective mining of 9.2 MT of near-surface, higher-grade tin mineralisation from the two main deposits.

Frenchvale Flake Graphite

Mount Cameron Minerals Inc. is working on the Frenchvale Flake Graphite Project on the graphitic marble and schist in Precambrian rocks on the eastern flank of the Boisdale Hills, at Frenchvale, 25km west of Sydney. The mineralised marble has been identified along a strike length of approximately 9.5km, with up to 300m wide zones. A 1,300m diamond-drilling program identified an area west of Campbell Lake where ten holes intersected up to 40m of high-grade graphitic marble, extending about 400m along the strike.

Mount Cameron Minerals Inc. has performed early-stage diamond drilling and geophysics on the property. Preliminary mineral processing studies have been conducted, and the results are promising.

A NI 43-101 report is being produced on this property and will be released shortly.

Brownfield Mineral Recovery

Nova Scotia is reviewing opportunities to secure critical minerals from waste. Nova Scotia has a centuries-long mining history, resulting in tailings material containing critical metals. These metals may now be economically recoverable because:

- Expected reduction in energy needs related to crushing and grinding activities (the material has previously been crushed and screened);

- Mineral processing techniques have improved, with the ability to recover minerals at lower concentrations economically; and,

- Certain minerals contained in tailings were not discovered and/or were not deemed to have value at the time of initial processing. Therefore, no attempt was made to recover them. Examples of these minerals may include germanium, gallium, indium, and rare earth elements, among others.

Additional benefits from reprocessing tailings may include a reduction in sulphides to limit acid-generating potential and to facilitate remediation and reclamation activities.

Nova Scotia’s potential in advancing Canada’s critical minerals supply chain

With Nova Scotia’s abundant natural resources, strong environmental principles, skilled labour, strategic location, strong business and academic communities, and favourable geology and location, the province is well-positioned to be a key player in the critical mineral sector, which will also create exciting opportunities for Nova Scotians. With a diverse geology that is favourable to finding new critical mineral deposits, as shown by the above examples, the future of Canada’s critical minerals supply chain is bright.

Please note, this article will also appear in the sixteenth edition of our quarterly publication.