Professor Lawrence C Scharmann from the University of Nebraska explains how the Darwinian evolutionary theory and common ancestry can be used as problem solving tools.

In the previous edition of The Innovation Platform, I put forward an argument for theory as the most powerful tool in the arsenal of the working scientist. Scientists, in fact, employ a naturalistic worldview that coalesces the theories and methodology of each of the major disciplines of science (e.g., biology, chemistry, geology, and physics) into working paradigms. Scientific paradigms are considered mature if they account for explanations between and among observations and provide a mechanism of action by which hypotheses (and predictions) can be tested resulting in new observations. Taking chemistry as an example: the periodic table of elements represents – through its rows and columns – relationships between elements; predictions can be made on the basis of valence shell electrons, tested, and results assessed/evaluated. Likewise for geology, continental drift represents predicted relationships between continents; plate tectonics illustrates geology’s mechanism of action. What theories, then, frame a biological sciences paradigm?

Nothing in biology makes sense, except in the light of evolution

Biology’s quest to be considered a mature science was initiated by Charles Darwin with the publication of On the Origin of Species2 in 1859. Naturalists quickly endorsed Darwin’s explanation for the relationships between similar species (i.e., common ancestry). Nonetheless, one of the arguments posed against evolution was that its supposed mechanism of action – namely natural selection – was considered conjecture at best since Darwin provided little in the way of evidence to support how natural selection might actually work. It was not until the 1930s when geneticists T.H. Morgan, Theodosius Dobzhansky, Ernst Mayr, and G. Gaylord Simpson noted that Mendel’s work from the 1850s provided the evidence necessary to explain natural selection as a mechanism of action for changes in species over time. The integration of evidence from genetics during this period became known as The Great Synthesis.

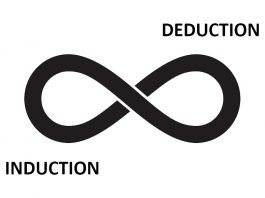

Ernst Mayr, considered to be the greatest evolutionist of the 20th century, provided an eminently accessible account of Darwin’s original work3. In One Long Argument, Mayr asserted that Darwin posed two major theories – natural selection and common ancestry (or modification with descent) – and three supporting or ancillary explanations – evolution (as change over time), multiplication of species, and gradualism to buttress his two major theories. It is to Darwin’s original work that contemporary biologists turn again and again for explanatory power, predictive capacity, and as problem-solving lenses as they seek to answer scientific questions and solve scientific puzzles. Darwin’s complementary theories – natural selection and common ancestry – allow us at any moment in time to consider conditional statements looking forward (natural selection) and into the past (common ancestry) and, in doing so, to look for and interpret new evidence.

Applying evolutionary theory in solving problems

Problem 1: change in human visual acuity over time – the use of natural selection as an explanatory tool

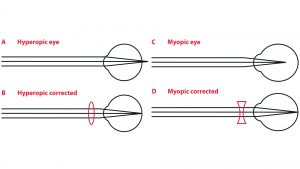

It can be observed that there are greater numbers of us requiring corrective measures to improve visual acuity than at any time in human history. In generation after generation it can be noted that the percentage of individuals needing improved visual clarity continues to rise. How can this be the case, when natural selection should predict just the opposite?

In other animals, variations exist in which individual members of a population possess an eye shape that is either too short or too long, creating conditions

of hyperopia (farsightedness) and myopia (nearsightedness). Natural selection would not favour extreme variations in eye shape for several obvious reasons because blurred vision makes the following more difficult:

- Foraging for food – the individual would be outcompeted by others possessing keener eyesight;

- Avoidance of predators – the individual would react more slowly than would another with greater visual acuity; and

- Finding reproductive mates – birds, for example, are highly sensitive to even slight variations in heritable characters and therefore avoid mating with individuals in possession of more extreme variations.

But humans are quite clever! Through the use of convex and concave lenses, visual acuity can be normalised across populations to the point where individuals born with sharper visual acuity have no advantage over those with more extreme variations. The result here is that by removing barriers that would normally advantage some individuals over others through natural selection, the human population has ensured that visual acuity will continue to deteriorate with time because the alleles responsible for hyperopia and myopia are being maintained in the gene pool. Human beings have, essentially, removed visual acuity as a biological character necessary for our individual survival.

Problem 2: vaccine production – the use of common ancestry as a problem-solving lens

The production of vaccines first occurred through trial and error methodologies. Edward Jenner, a British physician considered the founder of immunisation (at least in the Western hemisphere), observed that individuals working in the dairy industry experienced smallpox infection at a fraction of that of the general population. In March 1796, using matter from a dairy worker with fresh cowpox lesions on her arms and hands, Jenner deliberately scratched some of the matter into the arm of an eight-year old boy, James Phipps (how might Jenner have convinced Phipps’ parents to let him intentionally make the boy ill?). And, indeed, Phipps did develop some discomfort – he felt cold and lost his appetite – accompanied by a low-grade fever. Later that same year (July 1796), Jenner treated Phipps again, but this second time using material from a smallpox lesion. Again, as a parent this would have to have been quite a sales pitch! When no disease developed, Jenner was satisfied that Phipps was no longer susceptible to smallpox infection. Phipps’ parents were, I am sure, quite relieved.

While observations and treatments such as those administered by Jenner did occur, it was not until Darwin proposed common ancestry as one of the cornerstone theories of evolutionary biology that the production of vaccines accelerated and became routine. In hindsight, common ancestry provides an explanatory lens for Jenner’s success. By using the resemblance of a pox that infected a related mammal, cows, to that of a related pox that infected another mammal, humans, Jenner provided ex post facto evidence of the validity of common ancestry.

Today, every time we encounter a new infectious disease, the first question to be asked is ‘Does this new disease closely resemble other diseases that are already known?’ Asking this question and identifying logical similarities permits the potential development of a vaccine more quickly than it would otherwise occur – this happens yearly, for example, with influenza. When the answer, however, is that the infectious disease is novel and not sufficiently resembling an already known disease, the work to create a viable vaccine becomes more daunting. I will take up this topic in my next article, when I examine COVID-19, a novel coronavirus.

References

- Dobzhansky, T. (1973). ‚Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution‘. American Biology Teacher, 35, 125-129

- Darwin, C. (1859). On the Origin of Species. London: John

- Murray Publishers

- Mayr, E. (1993). One long argument. Charles Darwin and genesis of modern evolutionary thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Lawrence C Scharmann

Professor of Education

Department of Teaching, Learning, and Teacher Education

University of Nebraska

+1 402 472 2231

Lscharmann2@unl.edu

https://cehs.unl.edu/tlte/

Please note, this article will also appear in the fourth edition of our new quarterly publication.