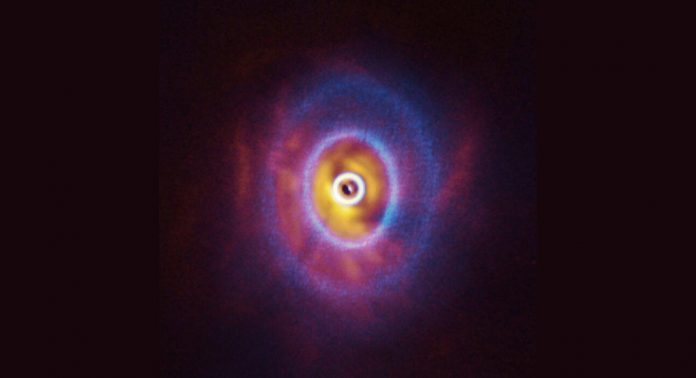

New research has revealed the first evidence that groups of stars can tear apart their planet-forming discs, leaving it warped and with tilted rings.

An international team of researchers has identified a stellar system where planet formation might take place in inclined dust and gas rings within a warped circumstellar disc around multiple stars.

The research is the first output of a programme on young stellar systems that uses an infrared imager, called MIRC-X. MIRC-X has been built by the Universities of Michigan and Exeter as part of a European Research Council-funded research project. The instrument has been designed to give new insights into how star and planet formation is taking place within the rotating, circumstellar discs of dense dust and gas surrounding young stars.

Stefan Kraus, professor of astrophysics at the University of Exeter, who led the research, said: “We’re really excited that our new MIRC-X imager has provided the sharpest view yet of this intriguing system and revealed the gravitational dance of the three stars in the system. Normally, planets form around a flat disc of swirling dust and gas – yet our images reveal an extreme case where the disc is not flat at all,” said Stefan Kraus.

Observations of the SPHERE instrument

The team observed the system with the SPHERE instrument on ESO’s VLT and with ALMA and were able to image the inner ring and confirm its misalignment. The team observed shadows that this ring casts on the rest of the disc. This helped them figure out the 3D shape of the rings and overall disc geometry.

This research reveals that this inner ring contains 30 Earth masses of dust, which could be enough to form planets. Alexander Kreplin of the University of Exeter, said: “Any planets formed within the misaligned ring will orbit the star on highly oblique orbits and we predict that many planets on oblique, wide-separation orbits will be discovered in future planet imaging surveys.

“Since more than half of stars in the sky are born with one or more companions, this raises an exciting prospect: there could be an unknown population of exoplanets that orbit their stars on very inclined and distant orbits.”

The group observed GW Orionis for over 11 years and mapped the orbit of the stars with unprecedented precision. The international team, with researchers from the UK, Belgium, Chile, France, and the US, then combined their observations with computer simulations to understand what had happened to the system. For the first time, they were able to clearly link the observed misalignments to the theoretical ‘disc-tearing effect’, which suggests that the conflicting gravitational pull of stars in different planes can warp and break their surrounding disc.