Scientists observe high-speed plasma turbulence that exceeds heat movement in the Large Helical Device (LHD).

In order to achieve a fusion power plant, it is necessary to stably confine a plasma of more than 100,000,000oC in a magnetic field and maintain it for a long duration. A team of scientists have discovered for the first time that turbulence moves faster than heat when heat escapes in plasmas in the Large Helical Device (LHD).

The research team is collaboratively led by Assistant Professor Naoki Kenmochi, Professor Katsumi Ida, and Associate Professor Tokihiko Tokuzawa of the National Institute for Fusion Science (NIFS) and National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS), Japan.

The team utilised measuring instruments developed independently, with the cooperation of Professor Daniel J den Hartog of the University of Wisconsin, USA.

Plasma turbulence

This turbulence makes it possible to predict changes in plasma temperature, and it is expected that successful observations of plasma turbulence will lead to the development of a method to make real time control of plasma temperature in the future possible.

In high-temperature plasma, turbulence is produced. This is confined by the magnetic field, and is a flow with vortexes of various sizes. This turbulence causes the plasma to be disturbed, and the heat from the confined plasma flows outward, resulting in a drop in plasma temperature.

To solve this problem, it is essential to understand the characteristics of heat and turbulence in plasma. However, the turbulence is so complex that full understanding has not yet been ascertained.

How the generated turbulence moves in the plasma is not known, because it requires specialised instruments that can measure the time evolution of minute turbulence with high sensitivity and extremely high spatiotemporal resolution.

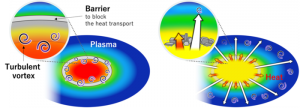

Left: Forming a barrier in the plasma to confirm heat inside. Right: By breaking the barrier, turbulence was discovered that moves faster than the heat, as the heat escapes from inside the plasma.

Creating strong pressure gradients in plasma

A ‘barrier’ can form in the plasma, which acts to block the transport of heat from the centre outward. The barrier makes a strong pressure gradient in the plasma and generates turbulence.

Assistant Professor Kenmochi and his research team have developed a method to break this barrier by devising a magnetic field structure. This method allowed them to focus on the heat and turbulence that flows forcefully as the barriers break, and to study their relationship in detail.

Then, utilising electromagnetic waves of various wavelengths, the researchers measured the changing temperature and heat flow of electrons and the millimetre-sized fine turbulence with accurate precision.

Previously, heat and turbulence had been known to move almost simultaneously at a speed of 5,000 kilometres per hour, which is approximately the speed of an aeroplane, but this experiment led to the world’s first discovery of turbulence moving ahead of heat at a speed of 40,000 kilometres per hour – the speed of this turbulence is close to that of a rocket.

Assistant Professor Naoki Kenmochi concluded: “This research has dramatically advanced our understanding of turbulence in fusion plasmas. This new characteristic of turbulence, that indicates it moves much faster than heat in a plasma, indicates that we may be able to predict plasma temperature changes by observing predictive turbulence. In the future, based on this, we expect to develop methods to control plasma temperatures in real-time.”