Sanjeev Kumar, Head of Policy at the European Geothermal Energy Council (EGEC), outlines the many ways in which geothermal energy provides the foundation for a full and inclusive transition away from the EU’s fossil-dominated energy system.

The best things come to those who wait. Geothermal energy has waited a long time for policymakers and politicians to notice it. Now it seems that they cannot get enough.

Many factors account for this interest. They range from serious attempts to meet the Paris Agreement’s net-zero emission reduction target to many local authorities grappling with the removal of fossil fuels from their heating systems, with local and competitive energy sources; the increased value of lithium; as well as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Geothermal energy is a mature technology that currently makes a small but significant contribution to Europe’s energy mix. However, it can do more. To meet the Paris Agreement targets and timetable, and to answer current energy challenges, it must do more.

We outline the five steps that need to be taken to help push geothermal from a niche to the mainstream.

Geothermal energy in Europe

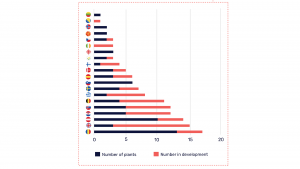

20 TWh of renewable electricity in Europe came from 3.4 GWe of installed capacity across 142 plants of varying sizes in 2022. The bulk of this baseload production came from three countries – Turkey (7.8 TWh), Italy (5.9 TWh), and Iceland (5.6 TWh).

Geothermal electricity is also produced in Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Austria and Portugal, whilst new capacity is being installed in Belgium, Slovakia, Greece, Switzerland, and the UK.

Unlike its more popular cousins – solar photovoltaic (PV) or wind – geothermal provides firm and flexible power. Its average capacity factor is higher than 80%, with some plants running at 100%. This means that an MWe capacity of geothermal is an order of magnitude different to its variable kin.

For example, in Croatia, a single 16.5 MWe capacity powerplant produced nearly as much renewable electricity as the 309 MWe of installed solar PV – 94 MWh and 96 MWh, respectively – in 2020.

Around 350 geothermal district heating and cooling systems were in operation in 2021. Fig. 1 indicates that 30 countries either have geothermal district heating systems or are in the process of installing systems.

During the energy price crisis, geothermal district heating systems were the only renewable solution to bring widespread relief to communities and cities. The picturesque Italian municipality of Ferrara reduced heating bills by 25% due to the fixed costs of geothermal heating.

The equally prestigious city of Szeged, located in southern Hungary, started a groundbreaking initiative to shift from fossil gas to geothermal energy in its district heating system in 2017. This already paid dividends as heating bills were half those of the fossil heating systems.

There are over two million geothermal heat pumps installed, with different sizes from ten to hundreds of kWth. The largest markets are Sweden and Germany, making up around half of the market. Many iconic buildings, such as the Bundestag; Elysée palace; NATO’s headquarters in Brussels; WWF Netherlands and UK offices; churches; hospitals; and schools opted for geothermal heat pumps because of their reliability and low operating costs.

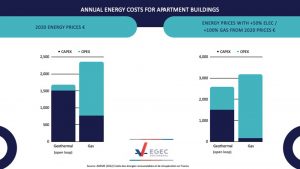

ADEME, the French energy agency, found that the operational costs of geothermal heating were considerably lower than fossil gas and that this became even more apparent when the impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine was factored into prices, especially multi-residential buildings, as highlighted in Fig. 2.

Unlocking geothermal energy in Europe

There are four actions that the industry, consumers, and policymakers need to address to realise geothermal energy’s full potential.

Start the conversation

Germany, France, Poland, and Ireland have national strategies to advance geothermal energy. Forthcoming legislation should provide the required regulatory certainty for rapid growth in each of these markets. Iceland moved to geothermal for heating and power in response to the oil shocks in the 1970s and is the leading player in Europe.

The Netherlands has a national hybrid heat pump strategy covering both geothermal and air-source heat pumps to facilitate its ban on fossil gas heating scheduled for 2026. Denmark made a vital change to its district heating law by removing price regulations for geothermal heat. The city of Aarhus will switch 35,000 homes to geothermal by 2030, and more projects are in the pipeline.

Securing more national approaches, combined with a European or international strategy, are key activities for the geothermal energy industry.

Change the scope

Heat is not as sexy as electricity or transport. At least not yet. It rarely gets mentioned in energy policy discussions, yet it accounts for nearly half of total global and European energy consumption.

Geothermal energy can provide baseload heating and cooling demand for buildings and low-to-medium temperature for industrial processes. To do so requires more focus on the logistics of the heat transition than the current incentive-driven schemes targeted at the wealthiest who can afford to benefit from tax breaks or loans.

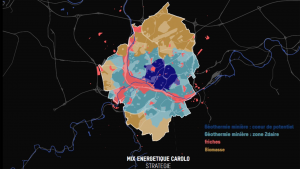

The most equitable solution is to empower local authorities to plan which local renewable sources are best placed to meet heating and cooling demand. This ensures energy efficiency in power consumption as well as resource efficiency in materials. Cities have already turned to geothermal energy. For example, the heat planning for Charleroi, in the Walloon region of Belgium, found that local shallow and deep geothermal reserves, combined with sustainable bioenergy sources, were sufficient to meet its heat demand, as outlined in Fig. 3.

Medium-temperature district heating infrastructure is currently being installed and large public buildings, including airports, are drawing up plans to invest in geothermal.

Heat zoning was a feature of the UK government’s 2019 Heat and Buildings Strategy, as well as new rules which are to be adopted in the updated EU Renewable Energy Directive, which mandates local authorities with over 35,000 inhabitants to design renewable heating and cooling strategies.

The challenge here is to ensure there is a sufficient supply of skilled local authority renewable heat planners and ensure they have access to geological data for their renewable heat planning.

Local authorities also require support to improve permitting processes and to manage the risk of such projects. This is the final challenge the sector needs to overcome to reach the mainstream.

Fix permitting

The permitting process is slow and cumbersome for geothermal, especially large-scale power projects. It needn’t be.

For geothermal heat pumps and open-loop systems, a ‘traffic light system’ indicating where installations can be made with a simple administrative notice; where a permit is required and where installations cannot happen due to competing subterranean uses; is the most efficient way to empower consumers and suppliers. This is used by German Lande, Austria, as well as parts of France and Italy.

It is essential that more of these ‘renewable go-to areas’, which the new Renewable Energy Directive prescribes, is established urgently.

Furthermore, the European Union introduced a fast-track permitting process to help deploy geothermal and air-source heat pumps to help displace the use of imported fossil gas from Russia.

Three additional actions are required. Firstly, permitting agencies require modernisation by shifting to online applications. Secondly, the application process must be smooth and time efficient with transparency on the process, stage of the application, and decision making. Finally, additional qualified capacity is required to ensure decisions can be made within the allotted timeframe.

Iceland established a national geothermal authority to oversee the permitting process and maintain high standards in project development and environmental stewardship. This is the template being pursued in Northern Ireland.

Fix risk

We don’t know what is below ground until we look. For large geothermal projects, not finding the resource, at the temperature originally budgeted for, could radically change the overall profitability of the project. This is a risk that many local authorities, who tend to seek city-wide renewable heating and cooling networks, cannot cover.

France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Hungary introduced national risk mitigation schemes to address this problem. The result is that France has the highest penetration of geothermal district heating systems globally. Hungary is rapidly upgrading its heating systems to replace dependency on imported fossil fuels.

During the energy price crisis, geothermal district heating systems were the only renewable solution to bring widespread relief to communities and cities

These national schemes are critical to the development of national geothermal supply chains. However, there is a need to either co-ordinate across borders or establish a European scheme to ensure that geothermal reaches its full potential everywhere.

This issue remains central to the future of the European geothermal sector and its growing customer base.

Geothermal will have a major role to play in the energy transition. The path is clear and the obstacles known. The pace at which Europe becomes climate neutral depends on how quickly these are addressed.

Please note, this article will also appear in the fourteenth edition of our quarterly publication.