Margherita Bruscolini, Geospatial Scientist and Drone Pilot at RSS-Hydro, discusses advances in Earth observation technology and introduces WASDI – an interoperable platform facilitating a variety of applications, including disaster response tools.

There is no doubt that remote sensing, or the acquisition of information about an object or a phenomenon without making physical contact, has seen significant progress in recent years. Remote sensing is mainly done using satellites (better known as Earth observation (EO), but also aircrafts and, more recently, drones. Alongside this, the need and desire for geospatial datasets to inform decision-making processes and to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are also clearly increasing.

Remote sensing has a wide range of applications in several fields and can be used to monitor the state of each component of the Earth system and their changes over time. This set of technologies allows one, for example, to monitor natural disasters such as flooding, hurricanes, earthquakes, and erosion; observe the ocean, land, and cryosphere; assess hazard risk and their impacts to develop preparedness strategies; to map, monitor and manage natural resources, for example in order to minimise the damage of urbanisation on the environment; and decide how to best protect natural resources.

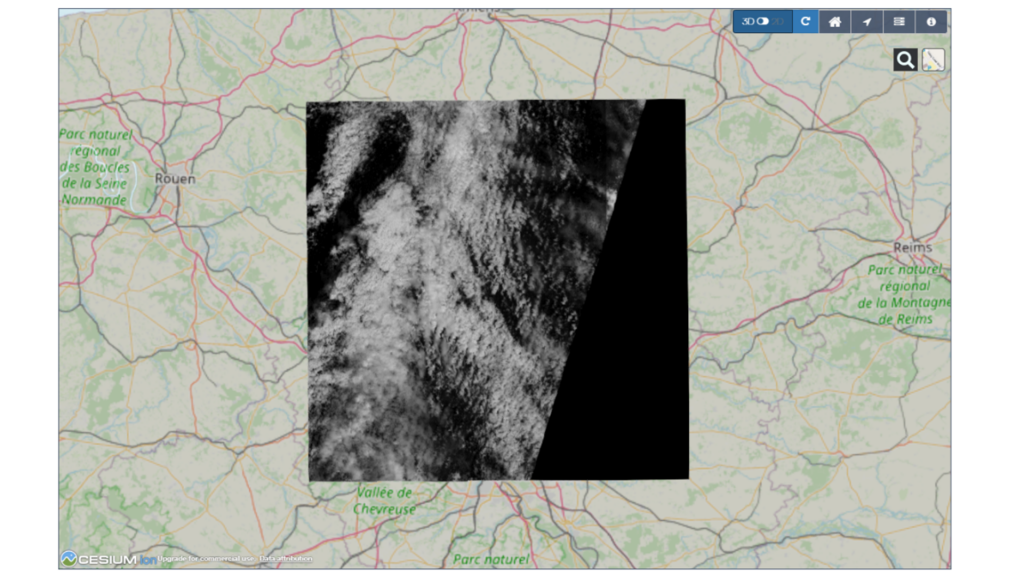

From space, a variety of satellite instruments, ranging from optical systems to synthetic aperture radars (SAR), compose images into distinctive spectral patterns that give us a unique perspective on our planet by showing us more than we can see with our own eyes. At a European level, the Copernicus programme, set out by the European Commission with the European Space Agency (ESA), attempts to unlock the full potential of satellites, opening the gates for citizens and professionals to easily use the large amounts of open-access information in a revolutionary push towards effective environmental monitoring and conservation.

Big data and digital optimisation

We have undoubtedly entered an era of big data and the Internet of Things (IoT), in which everyone and everything is connected across networks, transmitting and receiving seemingly an overload of information. In this context, the grand challenge now lies in ensuring sustainable and interoperable use, as well as optimised distribution of remote sensing products and services for science and end-user applications. To respond to these needs and challenges, industry, as well as public organisations and academia, are working on innovative solutions to create online platforms able to process big data in a convenient and optimised way.

With the ongoing proliferation of open-access satellite data, the number of downstream applications is rapidly growing. Developers of EO-based products and services, as well as expert and non-expert users of such tools, thus need access to a cloud computing infrastructure offering interoperable analysis functionality.

What is WASDI?

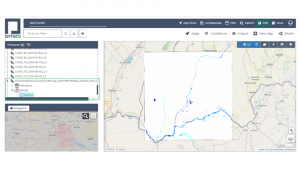

WASDI, the joint-venture start-up from the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST), RSS-Hydro, and the Italian IT company FadeOut Software, is a successful example of geo-enabling technology1. In fact, it consists of a Cloud-based infrastructure with a versatile online platform for EO experts and non-expert users alike. WASDI makes use of the full potential of Earth observation for a wide range of applications, developed by experts and deployed by users to process satellite images on demand and generate value-added content.

The system can make use of many different data providers, such as the ESA Copernicus Open Access Hub (SciHub) and the Luxembourg Space Agency (LSA) Data Center, both connected as external data providers. EO developers can use the various WASDI libraries that allow them to code and plug their algorithms to the platform in various languages, such as Python, Java, MATLAB/Octave, and IDL. Using the libraries, developers can search and ingest EO images, run workflows on the Cloud, and execute other processors.

A wide range of disaster response applications

At present, there are a number of EO application processing algorithms already available on the platform, including flooded area mapping from synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and optical satellite images, burned area mapping, and also the processing of spectral image bands from Sentinel-2 MSI (Multi-Spectral Instrument) into standard remotely-sensed indices, such as NDVI, NDWI, and NDSI. WASDI has also been used to map global human settlement from Sentinel-2 imagery2 and more complex physical process variables such as soil moisture from Sentinel-1 SAR3.

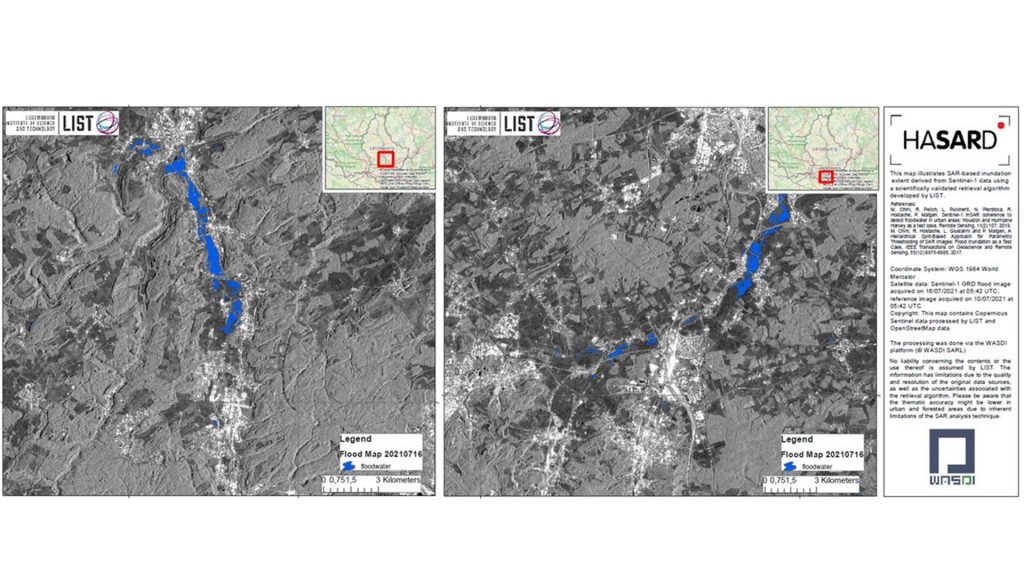

Currently, the most successful app on WASDI is based on the HASARD flood mapping algorithm, developed by the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST4). The automatic worldwide flooded area detection processor is based on Sentinel-1 SAR GRD (Ground Range Detected) image data. On WASDI, a user only needs to input the event date and the area of interest. Although other advanced parameters can be changed, this is all the system needs to search for pre- and post-event images and trigger the execution of HASARD to map flooded areas.

Apps that will be available in the near future on WASDI include flood mapping extensions for urban areas, flood depth estimation and reconstruction of flooded area under partial cloud cover in optical satellite images, currently under development by the RSS-Hydro’s IT team. Other planned apps include monitoring ship movements, global tropospheric nitrogen dioxide (NO2) visualisation using Sentinel-5P data, fractional canopy cover mapping, and an ML-based framework for SAR/optical data fusion.

Platforms such as WASDI offer the latest technology in Cloud computing functionalities, as well as in big data analytics to both EO product developers and users alike. The versatility of the online IT infrastructure presents EO experts with the possibility to develop and test algorithms on the fly, while non-expert users can execute those algorithms as seamless applications to generate map products in minutes, for any location, using any device. Such flexibility is greatly welcomed in the humanitarian and disaster response sectors, where actionable information is needed in minutes rather than days, as is currently most often still the case. Also, the fact that the system is always ‘on’, coupled with its ability to map any location over large areas and at a global level, offer great opportunities to a large variety of end-users.

The entire EO community has entered an era of global inter-connectivity. Now, more than ever, users and developers of EO products and services want to have everything, from data access and storage to computer processing and applications, as well as visualisation tools available online 24/7, in a secured environment. Even though the number of online EO platforms, offering similar functionalities, is constantly growing, there are only very few, if any, service providers that offer all these features.

References

1) G Schumann, P Campanella, et al, ‘An online platform for fully-automated EO processing workflows for developers and end-users alike’, IGARSS21, 2021

2) C Corbane, L Maffenini, and P Campanella, ‘Next Generation Mapping of Human Settlements from Copernicus Sentinel-2 data: leveraging cloud computing, machine learning and earth observation data’, Luxembourg, 2020

3) L Pulvirenti et al, ‘A surface soil moisture mapping service at national (Italian) scale based on Sentinel-1 data,’ Environmental Modelling & Software, 2018

4) P Matgen, R Hostache, G Schumann, L Pfister, L Hoffmann, and H H G Savenije, ‘Towards an automated {SAR}-based flood monitoring system: lessons learned from two case studies,’ Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Vol 36, pp. 241–252, 2011

Please note, this article will also appear in the eighth edition of our quarterly publication.