The Gemini South telescope in Chile has captured near-infrared images of the Carina Nebula with the same resolution that is expected of NASA’s Webb Telescope, demonstrating what we can expect when the orbiting observatory launches next year.

Using a wide-field adaptive optics camera that corrects the distortion caused by Earth’s atmosphere, Rice University’s Patrick Hartigan and Andrea Isella, and Dublin City University’s Turlough Downes used the 8.1 metre telescope to capture near-infrared images of the Carina Nebula.

Hartigan, Isella, and Downes describe their work in a study published in Astrophysical Journal Letters. The team gathered images of a molecular cloud about 7,500 light years from Earth. The images were collected at the international Gemini Observatory, as part of a programme of the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab.

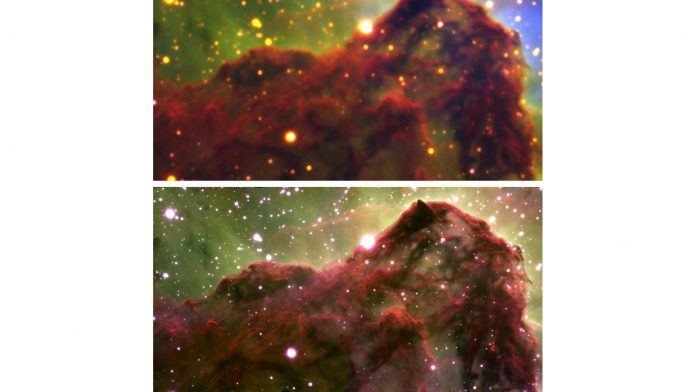

Hartigan said: “The results are stunning. We see a wealth of detail never observed before along the edge of the cloud, including a long series of parallel ridges that may be produced by a magnetic field, a remarkable almost perfectly smooth sine wave and fragments at the top that appear to be in the process of being sheared off the cloud by a strong wind.”

Using specially designed filters

The images reveal a cloud of dust and gas in the Carina Nebula known as the Western Wall. The cloud’s surface is slowly evaporating in the intense glow of radiation from a nearby cluster of massive young stars. The radiation causes hydrogen to glow with near-infrared light, the team used specially designed filters to capture separate images of hydrogen at the cloud’s surface and hydrogen that was evaporating.

An additional filter captured starlight reflected from dust, and combining the images allowed Hartigan, Isella and Downes to visualise how the cloud and cluster are interacting. Hartigan has previously observed the Western Wall with other NOIRLab telescopes and said it was a prime choice to follow up with Gemini’s adaptive optics system.

“This region is probably the best example in the sky of an irradiated interface,” he said. “The new images of it are so much sharper than anything we’ve previously seen. They provide the clearest view to date of how massive young stars affect their surroundings and influence star and planet formation.”

Images of star-forming regions taken from Earth are often blurred by turbulence in the atmosphere, an issue that can be eliminated by placing telescopes in orbit. One of the Hubble Space Telescope’s most iconic photographs, 1995’s ‘Pillars of Creation’, captured the grandeur of dust columns in a star-forming region, however, the beauty of the image belied Hubble’s weakness for studying molecular clouds.