A study led by UC San Diego researchers has discovered that there is a significant amount of slow-building solar flares worthy of further investigation.

Solar flares have been classified based on the amount of energy they emit at their peak.

However, there has not been a significant study into differentiating flares based on the speed of energy build-up since slow-building flares were first discovered in the 1980s.

Therefore, the research, ‘Solar Flare Catalogue from 3 Years of Chandrayaan-2 XSM Observations,’ is the first of its kind in this field.

Why do these flares occur?

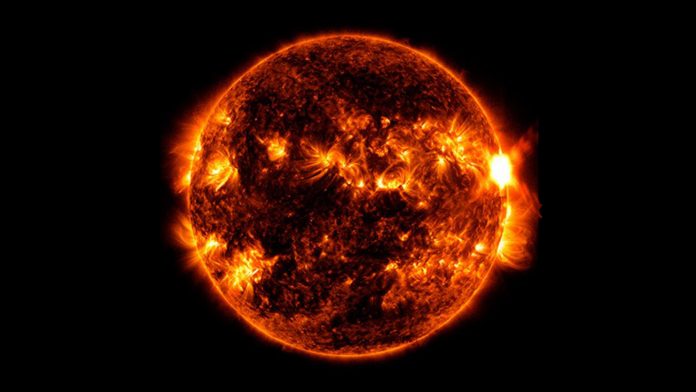

Solar flares occur when magnetic energy builds up in the Sun’s atmosphere and is released as electromagnetic radiation.

Lasting anywhere from a few minutes to a few hours, flares usually reach temperatures around ten million degrees Kelvin.

Because of their intense electromagnetic energy, solar flares can cause disruptions in radio communications and Earth-orbiting satellites, and even result in blackouts.

The width-to-decay ratio of a flare is the time it takes to reach maximum intensity to the time it takes to dissipate its energy.

Most commonly, flares spend more time dissipating than rising. A five-minute flare may take one minute to rise, and four minutes to dissipate for a ratio of 1:4.

How do slow-building solar flares differ?

With slow-building solar flares, that ratio may be 1:1, with 2.5 minutes to rise and 2.5 minutes to dissipate.

Aravind Bharathi Valluvan, who led the study, was a student at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IITB) when this work was conducted.

Exploiting the increased capabilities of the Chandrayaan-2 solar orbiter, IITB researchers used the first three years of observed data to catalogue nearly 1400 slow-building solar flares – a dramatic increase over the roughly 100 that had been previously observed over the past four decades.

It was thought that solar flares were like the snap of a whip – quickly injecting energy before slowly dissipating.

Now, seeing slow-building flares in such high quantities may change that thinking.

“There is thrilling work to be done here,” stated Valluvan, who now works in UC San Diego Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Steven Boggs’ group.

“We’ve identified two different types of flares, but there may be more. And where do the processes differ? What makes them rise and fall at different rates? This is something we need to understand,” he concluded.