For many years, public-private partnerships have been gaining increasingly more interest around the world, especially in the flood disaster response sector.

Now more than ever, it is clear that disasters do happen at a global scale and can impact all of us at the same time. There are many different types of disasters and some are more devastating than others, but the devastation and impact of flood disasters happen very much at the community level and their severity depends on local exposure, flood disaster response and individual vulnerability but with often global consequences.

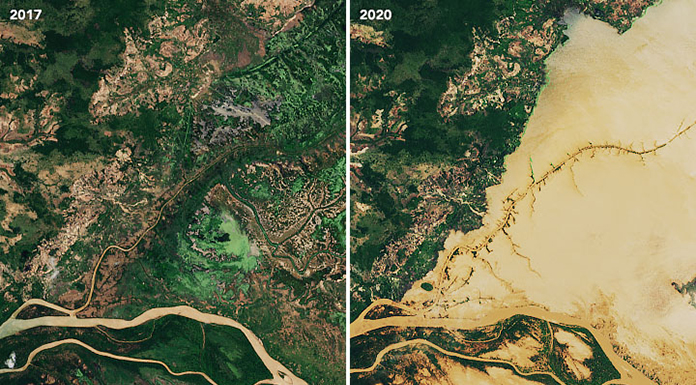

By its nature, flooding is a disaster of localised impacts with far-reaching consequences, affecting many of us all around the world every year. Indeed, during the last decade, flooding has moved to the most top-ranked natural disaster. Already this year, there have been several severe floods in many parts of the world affecting many tens of thousands of people, causing substantial damage and considerable loss of lives.

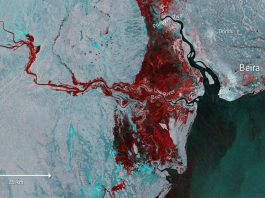

In January this year, large-scale flash floods in Indonesia, Mozambique and Madagascar affected 1000s of people. Widespread flooding as a result of heavy winter storms affected also many areas in the North-West and South-East of the US in February and many parts of Ohio and Indiana during the end of March. There has been a high flood alert for early Spring along most of the Mississippi River and its major tributaries. In Europe also, the widespread February floods in the northern parts of the United Kingdom caused considerable damages, with insured losses now estimated at over $360m (~€331.7m), according to PERILS AG. Moreover, the flash floods in the coastal areas of eastern Spain in early April left many trapped in their homes and in need of rescue at a time when all of Spain, like most countries in the world, was being hit hard by COVID-19 and most people were confined to their homes.

These recent events clearly illustrate the need for better flood prediction at the global level, and for more frequent, actionable flood observations, as well as more effective response and resilience strategies. This is particularly necessary because disastrous events are simultaneously occurring in different places and can happen jointly with other types of disasters – a situation many people who are currently being affected by floods are going to be experiencing amidst the devastating consequences of the global Coronavirus crisis.

Photo credit: UN WFP/Michael Manalili

Formalising PPPs to boost business and innovation

Over the past few months, we have seen large amounts of solidarity amongst many communities, businesses and authorities in the fight against COVID-19. Volunteering efforts are increasing, along with the number of new partnerships and initiatives aiming to help local communities and businesses survive during this global pandemic.

However, during these devastating times, it is obvious that not only most resources of national governments and international organisations are directed towards battling COVID-19, but also the mainstream media are focusing the global populations attention on the Coronavirus crisis. Unfortunately, this is happening clearly at the detriment of many other ongoing disasters, such as floods. In fact, the halting of many activities over the last couple of months is not only having long-term negative impacts on national and international markets and economies but also on sustaining vital geospatial data streams that directly affect global weather predictions, climate modelling and many research and aid development projects that are also looking at floods. This situation is unprecedented, and many projects, partnerships and initiatives deserve proper re-evaluation and rethinking.

Photo credit: UN WFP/Michael Manalili

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can be loosely defined as cooperative institutional arrangements between public and private sector actors. Often, PPPs are institutional arrangements for co-operation expressed through the establishment of new organisational units.1 Supposedly, PPPs provide opportunities for innovation due to the long-term perspective, the use of output specifications and the collaborative environment. Literature suggests that the dynamics between procurers and consortia influence the actual contribution of these conditions to innovative practices. However, several cases have shown that there is often limited innovation and a lower-than-expected value generation due to the absence of a formally binding and cost-effective collaboration scheme among the consortium members, which would be needed in order to ensure innovation.2

In the face of an increasingly costly cycle of flood damages and repairs, international organisations, national governments, and localities are looking closely at mitigation and resilience measures to decrease losses while improving long-term sustainability.3 With a general lack of quality data, needed financial resources and the necessary know-how in many places in the world, this is easier said than done. Further complicating the situation is uncertainty about when the expected benefits of measures would materialise. Many local and regional authorities, as well as governmental entities, need to make the business case of why pre-disaster mitigation is crucial in building resilient communities (which is a non-trivial task). Partnerships between levels of government or non-governmental public organisations and with the private sector can help overcome these issues. For instance, procurements between flood model vendor companies, Earth observation data analytics companies and international aid organisations have been responsible for much of the recent geospatial innovations in services utilised by humanitarian and aid development sectors.

Photo credit: UN WFP/Michael Manalili

The importance of PPPs for sustainable development

In the same context, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) recognise multi-stakeholder partnerships as important vehicles for mobilising and sharing knowledge, expertise, technologies and financial resources to support the achievement of the sustainable development goals in all countries, particularly developing countries.4 UNSDG-17 further encourages effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships.

PPPs can support co-operation and also facilitate access to science, technology and innovation and enhance know-how sharing. Of course, this needs to happen on mutually agreed terms, including through the improved co-ordination between existing institutional structures and mechanisms. The formalisation of PPPs can help accelerate the take-up and operationalisation of both science and technology. In this context, innovation capacity-building mechanisms are operated by several UN divisions and other large organisations and are implemented in a number of developing countries. Such innovation programs enhance the use of enabling technologies, and for flood disaster resilience, mitigation and response, these programs are particularly promoting the use of novel remote sensing technologies (including satellites and drones) for improving global flood prediction and alerting.

Photo credit: UN WFP/Michael Manalili

PPPs to accelerate research innovation

PPPs can also help accelerate research innovation. A great example is the NASA and Europe Frontier Development Lab (FDL). Building on PPPs, the FDL’s goal is to address fundamental knowledge gaps in a variety of fields, including climate change, disaster response, astrobiology, and space exploration. This demands the synergistic analysis of vast amounts of data from diverse scientific domains and sources, including planetary and space missions, ground-based telescopes, field and lab experiments, and theoretical modeling.5 Through powerful public-private partnerships, the FDL brings together space agencies and other public organisations active in the various domains with big industry players in the fields of space, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and geospatial Big Data analytics, with the goal to accelerate innovation.

Every year, several teams composed of mentors and research participants are formed to solve current challenges posed by the public partner organisations. Moreover, leading technology industry partners are providing the necessary compute engines and analysis platforms to deal with the data and computational requests. In the context of floods and flood mapping, one of the FDL Europe teams in 2019 pioneered an AI-based onboard flood map processor for optical sensors carried on small satellites.6 If implemented on low-cost orbital hardware in the future, this concept could be game-changing for many flood-response teams all over the world.

References

- Hodge, G. A., and Greve, C. 2007. Public–Private Partnerships: An International Performance Review. Public Administration Review, 67: 545-558. DOI:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00736.x

- Parrado, S., & Reynaers, A.M. 2018. Agents never become stewards: explaining the lack of innovation in public–private partnerships. International Review of Administrative Sciences. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852318785024

- Tompkins, F. 2019. Public-Private Partnerships can help reduce flood damage and cost, officials say. The Pew Charitable Trusts. August 14, 2019. Accessed 6th April 2020. Available at:https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2019/08/14/public-private-partnerships-can-help-reduce-flood-damage-and-costs-officials-say

- The United Nations. 2020. Multi-stakeholder partnerships and voluntary commitments. Division for Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. Accessed 6th April 2020. Available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdinaction

- Cabrol, N. A., Diamond, W. H., and Bishop, J. et al. 2018. Advancing Astrobiology Through Public/Private Partnership: The FDL Model. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Vol. 49. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, p. 1275

- Mateo-Garcia, G., Oprea, S., and Smith, L. et al. 2019. Flood Detection On Low Cost Orbital Hardware. arXiv, eess.IV. Available at: https://arxiv.org/abs/1910.03019

Dr Guy Schumann

CEO and Principal Scientist

RSS-Hydro Sarl-S

+352 206005 6301

rss-hydro@outlook.com

www.linkedin.com/company/rss-hydro

www.rss-hydro.lu

Please note, this article will also appear in the second edition of our new quarterly publication.