Is the UK’s materials industry ready to be part of the circular economy; and what more can be done to implement a sustainable circular approach?

The circular economy and activities related to it have evolved quite dramatically over the last 6 months. With the European Commission stepping up its efforts and channelling public funding totalling more than €10 billion to circular economy activities, the movement is now quickly becoming mainstream across Europe and the UK.

First Vice-President of the EU Commission Frans Timmermans says: “Circular economy is key to putting our economy onto a sustainable path and delivering on the global Sustainable Development Goals. The Circular Economy Action Plan report shows that Europe is leading the way as a trail blazer for the rest of the world. At the same time more remains to be done to ensure that we increase our prosperity within the limits of our planet and close the loop so that there is no waste of our precious resources.”

This very positive and encouraging statement is clearly backed up by quantifiable examples across Europe, but what about the UK? Are British companies working to the same playbook? With the publication in December 2018 of “Our Waste, Our Resources: A strategy for England” by the British government and the similar “Making Things Last – A Circular Economy Strategy for Scotland” by the Scottish Government, it seems as though the UK is playing by the same rulebook. In truth, however, it only initially appears that way.

To date there has not yet been a peer-reviewed and universally accepted definition of what the circular economy really is. Many UK companies still consider the concept to refer purely to more responsible recycling practices. Some say it is a linear model made circular. Others state that the circular economy concept has the potential to become a “greenwashed” idea, which will not gain financial advantage in the long term. In answer to a global investigative report, the World Business Council on Sustainable Development found that safe materials were cited by all its respondents as being the primary element of critical importance for an effective sustainable circular economy.

To effectively and responsibly move from a linear economy to a circular economy, companies, society and governments all require a significant transition from the current industrial culture and business state of mind. Thinking circularly must evolve and be implemented. In the UK there are still only a small number of tangible examples of circular business implementation and products definitively designed for a circular economy.

There is also a hidden circularity problem. Currently, most materials chosen for use in the millions of products we make, distribute, sell, buy and use today have never been evaluated for their fitness for purpose from a safe cycling and circular economy perspective.

As a result of the screening of David Attenborough’s Blue Planet II, we are all now very aware of the critical example of plastics not being designed for purpose, from a circularity viewpoint. Plastic is an inert substance which was created out of human necessity from as early as 1600 BC in the form of natural rubbers, evolved throughout the 1900s to numerous chemical augmentations; and eventually delivered one of Earth’s most prolific petrochemical substances in current 21st century use.

Considerations for the environmental and ecological impacts of this highly versatile substance was never a real concern for the inventors and chemists back in the early 20th century. Ease of manufacture and low cost were the overriding factors motivating plastic innovation. Back then there was a demand and industry provided a solution.

Now, this landscape has changed and evolved dramatically; and responsibility for plastic waste is being shifted from pillar to post. From households being asked to recycle plastics, to companies being asked to manufacture responsibly and city councils being asked to take responsibility for waste plastic. Who is actually responsible for this plastic problem? The truth is, we are ALL responsible for our part in the solution.

Plastic material is not inherently the problem. The effective custodianship and wise management of the material, however, is.

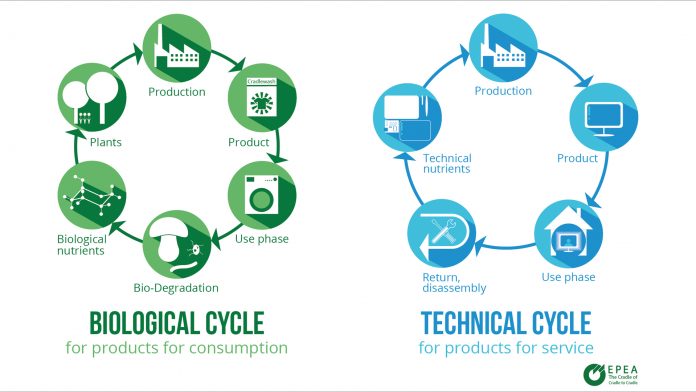

This creates a great opportunity. We can now zero in on the key element of materials, the factor most commonly agreed to be vitally needed to create a healthy, safe and sustainable circular economy. Material health assessments of the appropriate chemicals and materials are necessary to define their safe cycling. This occurs in either a technical or biological metabolism or closed cycle as nutrients for future use in perpetuity.

Product and system designers now need information on the human and environmental characteristics of their material choices – considering performance and aesthetic characteristics, instead of only cost. By knowing the specific technological and biological components of products, we can determine a material’s suitability to cycle safely in each metabolism, their likely unintended impacts and post-use behaviour for materials reuse.

Numerous influential organisations across the UK are gladly committing to defining this type of materials circularity in both their business and ecological strategies. The Environment Agency in London has signalled its intention to make use of Cradle to Cradle® Certified, circular economy ready materials for their TEAM2100 (Thames Estuary Asset Management 2100) 10-year asset management programme. Zero Waste Scotland has defined the use of circular economy ready materials in the built environment as part of their circular economy strategy for the Scottish construction industry. Cradle to Circular Design Consultancy UK has launched their “Zero X’s” materials assessment programme which offers a quick scan or inventory of all chemical ingredients in products. The programme aims to eliminate harmful and negatively impactful chemical and materials from both human and environmental centred design.

The programme defines materials used in products as neither “good” or “bad” – they are just materials made up of elements and compounds from the periodic table of elements. We can, however, define a material’s suitability to cycle safely as technical or biological nutrients given knowledge of the material composition, intended use, likely unintended uses and post-use behaviour for the products. We need to understand and improve material choices in products at each design iteration, based on their suitability for safe cycling in a circular economy after use. A product intentionally designed for the circular economy would naturally include consideration of all the five core elements of the Cradle to Cradle® Design Framework, including material health, material reutilisation, water stewardship, renewable energy and social fairness.

The task set before us all in terms of circularity of the daily materials we humans utilise is vast and challenging. Thankfully, we now have the requisite tools, expertise and abilities to meet and even exceed the challenges we face in the transition from a linear to a circular economy.

Together we can do it.

Brendon Rowen

Cradle to Cradle Marketplace Limited

+44 (0) 7747411585