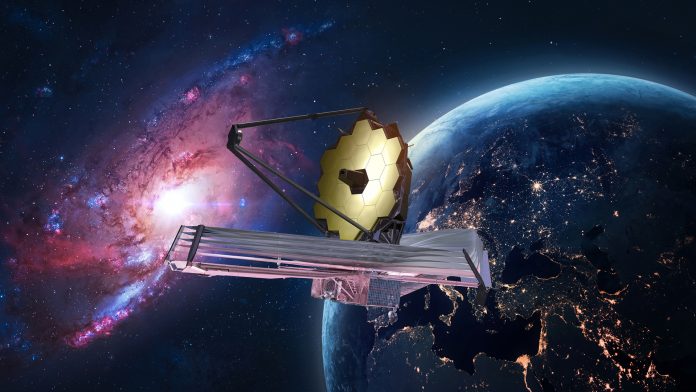

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has revealed a detailed molecular and chemical portrait of an exoplanet’s skies.

The space telescope’s variety of highly sensitive instruments was trained on the atmosphere of WASP-39b, a distant planet that is about the size of Saturn and orbits a star around 700 light years away.

JWST and other space telescopes, such as Hubble and Spitzer, have previously identified isolated ingredients of the planet’s atmosphere. However, the new data, observed by the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, provides a full menu of atoms, molecules, and signs of chemistry and clouds.

The space telescope revealed the most detailed observations yet

“The clarity of the signals from a number of different molecules in the data is remarkable,” said Mercedes López-Morales, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics and one of the scientists who contributed to the new results.

“We had predicted that we were going to see many of those signals, but still, when I first saw the data, I was in awe.”

The new revelations from the space telescope also shed light on how clouds in exoplanets might look up close: broken up rather than a single uniform blanket over the planet.

The findings bode well for the capability of JWST to conduct a broad range of investigations on exoplanets — planets around other stars — scientists hoped for. That includes probing the atmospheres of smaller, rocky planets like those in the TRAPPIST-1 system.

“We observed the exoplanet with multiple instruments that, together, provide a broad swath of the infrared spectrum and a panoply of chemical fingerprints inaccessible until JWST,” explained Natalie Batalha, an astronomer at the University of California, who contributed to and helped co-ordinate the new research. “Data like this is a game changer.”

A surprising detection of sulphur dioxide

The range of discoveries by the space telescope makes up a set of five brand new scientific papers. Among the new revelations is the first ever recorded trace of sulphur dioxide in an exoplanet atmosphere, a molecule produced from chemical reactions triggered by high-energy light from the planet’s parent star. On Earth, the protective ozone layer in the upper atmosphere is created in a similar way.

“The surprising detection of sulphur dioxide finally confirms that photochemistry shapes the climate of hot Saturns,” stated Diana Powell, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics and core member of the team that made the sulphur dioxide discovery. “Earth’s climate is also shaped by photochemistry, so our planet has more in common with hot Saturns than we previously knew.”

Jea Adams, a graduate student at Harvard and researcher at the Center for Astrophysics, analysed the space telescope data that confirmed the sulphur dioxide signal.

“As an early career researcher in the field of exoplanet atmospheres, it’s so exciting to be a part of a detection like this,” Adams said. “The process of analysing this data felt magical. We saw hints of this feature in early data, but this higher precision instrument revealed the signature of SO2 clearly and helped us solve the puzzle.”

Further observations of WASP-39b

With an atmosphere comprised mostly of hydrogen and an estimated temperature of 1,600°F, the exoplanet is not believed to be habitable. However, the new space telescope data paves the way for finding evidence of life on habitable exoplanets.

The planet’s proximity to its host star – eight times closer than Mercury is to our Sun – also makes it a laboratory for studying the effects of radiation from host stars on exoplanets. Better knowledge of the star-planet connection should bring a deeper understanding of how these processes create the diversity of planets observed in the galaxy.

Other atmospheric constituents detected by JWST include sodium, potassium, and water vapour, confirming previous space and ground-based telescope observations as well as finding additional water features, at longer wavelengths, that haven’t been seen before.

The space telescope also identified carbon dioxide at a higher resolution, providing twice as much data from previous observations. Meanwhile, carbon monoxide was detected, but obvious signatures of both methane and hydrogen sulphide were absent from the data. If present, these molecules occur at very low levels, a significant finding for scientists making inventories of exoplanet chemistry in order to better understand the formation and development of these distant worlds.

Capturing such a broad spectrum of WASP-39b’s atmosphere was a scientific tour de force, as an international team independently analysed data from four of JWST’s finely calibrated instrument modes. They then made detailed inter-comparisons of their findings, yielding more scientifically accurate results.

JWST: Viewing the world in infrared light

JWST views the universe in infrared light, on the red end of the light spectrum beyond what human eyes can see. This unique feature allows the space telescope to pick up chemical fingerprints that are unable to be detected in visible light.

To detect light from WASP-39b, the telescope tracked the exoplanet as it passed in front of its star, which allowed some of the star’s light to filter through the planet’s atmosphere. Different types of chemicals in the atmosphere absorb different colours of the starlight spectrum, so the colours that are missing tell astronomers which molecules are present.

By so precisely analysing an exoplanet atmosphere, the JWST instruments performed well beyond scientists’ expectations, and promise a new phase of exploration among the broad variety of exoplanets in the galaxy.

López-Morales concluded: “I am looking forward to seeing what we find in the atmospheres of small, terrestrial planets.”