New study is the first to explore the relationship between oxygen, temperature, and metabolic requirements of certain marine animals.

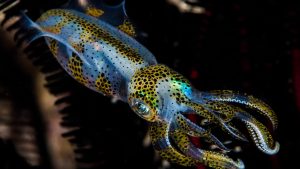

Not all marine animals find that the warming oceans shrink their viable habitats. Around 20 years ago, jumbo squids, which historically live in more tropical latitudes, showed up in record numbers near the coast of central California. These voracious eaters feasted on hake, rockfish, and other commercially important species, disrupting the local supply chain. At the time, there was not a clear reason as to why this happened, with scientists proposing that the squids arrived due to a combination of climate change and overfishing.

Now, a team of researchers, led by Brad Seibel, a professor and marine physiology expert at the University of South Florida, is aiming to shed light on this event and is further analysing the responses of different animals to warming oceans.

The paper, titled ‘Unique thermal sensitivity imposes a cold-water energetic barrier for vertical migrators,’ was published in Nature Climate Change.

Responses to climate change

“The basic narrative in recent years has been that as the ocean warms and loses oxygen, animals in it will be chased out of their native habitat and move into cooler waters in more northern latitudes,” Seibel said. “But this is an oversimplification.”

Marine animals will not react to climate change in the same way as each other.

The study looked at the relationship between oxygen, temperature, and the metabolic requirements of vertical migrators. These include billions of marine animals from tiny crustaceans called krill to jumbo squids. Seibel, alongside his co-author, Matt Birk, Seibel’s former graduate student and professor at Saint Francis University in Pennsylvania, used modelling to understand how six species of krill and the jumbo squid would metabolically react to varying parameters that approximate day and night habitats.

“Vertical migrators buck the basic narrative, which is based largely on studies of coastal animals,” Seibel said.

As the oceans continue to warm, vertical migrators that live in tropical zones, such as squid, are likely to expand their habitat northward. This does not mean that they necessarily leave their native tropical zones.

Seibel argued that this is likely to have happened 20 years ago when jumbo squids showed up in record numbers on California’s coast. At that time, instead of climate change causing the migration, an El Nino event temporarily brought warmer water to the coast. This can be thought of as a short-lived climate change model.

The warmer water enabled the squid to expand their range northward, where they were able to take advantage of new food sources, even though there was plenty of food in the tropical regions.

“It wasn’t that they didn’t have enough oxygen or that it was too hot for them further south; before the El Nino event, it was too cold for them up north,” said Seibel. This nuance matters, and is related to their metabolic requirements.

Vertical migrators compared to coastal species

Coastal species experience a fairly consistent supply of oxygen in waters well mixed with the atmosphere, in comparison to vertical migrators, which live at depth during the day. At depth, it is cold and dark, and there is less oxygen. Vertical migrators travel toward the relatively warm ocean surface at night to eat, where the oxygen is plentiful and it is safer to forage.

“This study is a good example of the fact that the conclusions we often draw from well-studied, and easy to catch, organisms may not hold true for the greater diversity of species and lifestyles found in the oceans,” Birk said.

The researchers concluded that the metabolic rates of vertical migrators were affected by temperature by four to five times more than most coastal species. For example, when the squids are at depth, they do not do much at all, but when migrating to shallower waters for a meal, their metabolic rates significantly increase.

By incorporating the heightened effects of temperature on the vertical migrators’ metabolic rates in their models, the researchers found that climate change will expand the available habitat of vertical migrators to the north and south by as much as ten to 20 degrees of latitude by the end of the century.

“We really need to drill down into animal physiology and better understand the ways that various species evolve and adapt to environmental conditions,” said Seibel.