The three-year Horizon 2020 SOMIRO project has developed swimming, solar-powered milli-robots to gather data on crop performance and pesticide use.

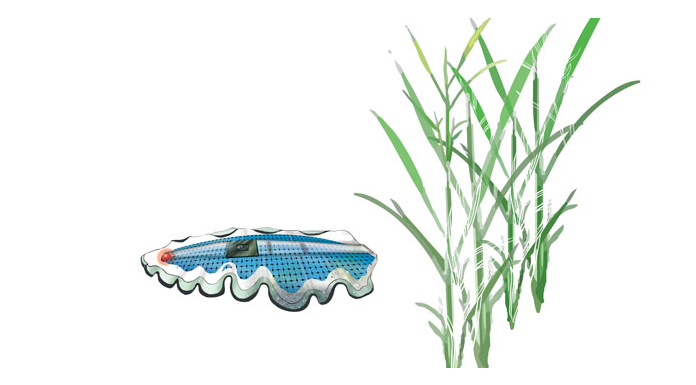

With a budget of approximately €2.9m, the SOMIRO project aims to develop technology that will help to reduce the environmental impact of agriculture. The team are currently focusing on the development of flatworm-inspired milli-robots, which will help farmers monitor their plants and mitigate the overuse of pesticides and nutrient supplements by gathering data on crop performance and pesticide use.

Klas Hjort, Project Coordinator and Professor at the Division of Microsystems Technology, said: “These tiny robots are designed to run solely on the energy naturally available in the environment – in this case sunlight.”

The final version of this milli-robot will house a motor, solar cells, and wireless sensors. Hjort continued: “This insect-sized structure has a total power output of 1.5 milliwatts. However, of that just 0.1 milliwatts or 100 microwatts is used for the electronic components for communication, intelligence, and for chemical sensors. The remaining 90% or so of the milli-robot’s energy is used to run the motor.”

The environmental analyses of water crops

The goal is to be able to use the technology for environmental analyses of crops grown in water such as rice, or various types of liquid-based animal husbandry such as in aquaponic farms. In these contexts, the milli-robot will be able to measure chemical concentrations and map the carbon footprint, eutrophication, and the overuse of pesticides and feed.

Hjort said: “With ten milli-robots, we can easily cover around two hundred square metres and get a clear understanding of, for example, how much fertiliser or arsenic there is in a rice field. The robot’s sensor systems mean that it can independently seek out those places that are the most interesting for taking measurements, thereby helping to make agricultural practices as good and sustainable as they can be.”

Hjort believes that each robot could eventually cost no more than a few hundred Swedish kronor, which would make them accessible to local farms and farmers in developing countries.