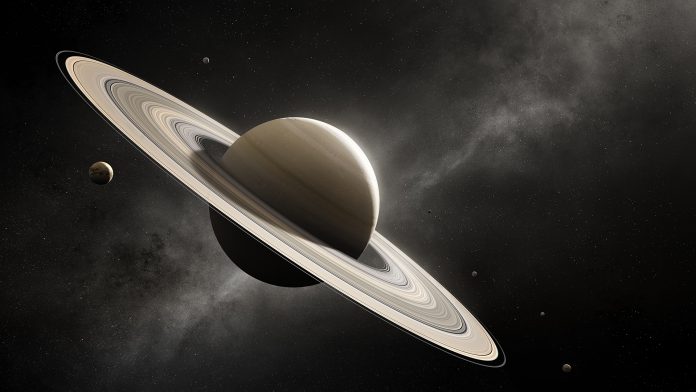

A new study performed by MIT astronomers suggests that an ancient, missing moon may have caused Saturn’s rings and the planet’s tilt.

The groundbreaking modelling study provides fascinating insights into Saturn’s evolution. Today, the giant gas planet hosts 83 moons; however, the MIT team believe that many moons ago, an extra satellite they named Chrysalis was pivotal for causing Saturn’s rings and tilt.

The mysterious rings of Saturn

The rings of Saturn swirl around the planet’s equator, rotating at a 26.7-degree angle relative to the plane that it orbits the Sun. Astronomers hypothesised that this tilt was due to gravitational interactions from its neighbour, Neptune, as Saturn’s tilt precesses nearly the same rate as Neptune’s orbit.

However, despite potentially being in sync at one time, Saturn has since released Neptune’s pull. So what could have caused Saturn’s rings and tilt? MIT astronomers believe the missing moon Chrysalis was instrumental, pulling and tugging Saturn for billions of years, keeping its tilt in line with Neptune.

Then, around 160 million years ago, Chrysalis became unstable and came too close to its planet in a grazing encounter that ripped the moon apart – enough force to remove Saturn from Neptune’s grasp, leaving it with the tilt we see today. Moreover, the researchers believe that some of the shattered fragments from Chrysalis remained suspended in orbit, eventually breaking into small icy chunks to form the planet’s signature Rings.

Jack Wisdom, professor of planetary sciences at MIT and lead author of the new study, commented: “Just like a butterfly’s Chrysalis, this satellite was long dormant and suddenly became active, and the rings emerged.

Unravelling Saturn’s tilt

Scientists in the early 2000s theorised that Saturn’s tilt was due to the planet being trapped in a gravitational association with Neptune. However, a new twist to the mystery was added by observations from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017.

They revealed that Titan, the planet’s largest moon, was moving away from the planet at a faster rate than expected – around 11 centimetres each year. Titan’s rapid migration and gravitational pull led scientists to believe that the moon was responsible for Saturn’s tilting and keeping the planet in sync with Neptune.

However, this depends on Saturn’s moment of inertia – how mass is distributed in the planet’s interior, meaning the tilt could behave differently if the matter is more concentrated at its core or towards the surface.

Wisdom said: “To make progress on the problem, we had to determine the moment of inertia of Saturn.”

Discovering Chrysalis

In their new study, the astronomers looked to pinpoint Saturn’s moment of inertia utilising some of Cassini’s last observations, in which it closely approached the planet to map its gravitational field precisely. The gravitational field can be used to estimate the distribution of the planet’s mass.

The team modelled Saturn’s interior, identifying mass that matched the gravitational field that Cassini observed. They found that this new moment of inertia placed Saturn outside of resonance with Neptune.

“Then we went hunting for ways of getting Saturn out of Neptune’s resonance,” Wisdom explained.

The team performed simulations to map the evolution of Saturn’s orbital dynamics and its moons to see if this could have influenced Saturn’s rings or tilt, but this was not the case. Next, they reexamined the mathematical equations of the planet’s precession, identifying that if one of Saturn’s moons were missing, it could affect its tilt.

Subsequently, the astronomers ran simulations to illuminate the properties of the missing moon, such as its mass and orbital radius and dynamics, that could have knocked Saturn out of sync. They determined that the loss of Chrysalis, which was around the size of the planet’s third-largest moon – Iapetus – was enough to knock it out of resonance.

Between 200 and 100 million years ago, Chrysalis entered a chaotic orbital zone, closely encountering Iapetus and Titan, eventually coming too close to Saturn, which ripped the moon apart and formed Saturn’s rings and modern-day tilt.

Wisdom concluded: “It’s a pretty good story, but like any other result, it will have to be examined by others. But it seems that this lost satellite was just a Chrysalis, waiting to have its instability.”