A research team from Lund University has mapped the movement of white dwarfs in the Milky Way, revealing information about these perplexing stars.

What is a white dwarf?

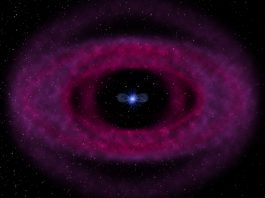

White dwarfs were once normal stars, similar to the Sun, however they eventually collapse after exhausting all of their fuel. White dwarfs have a radius of about 1% of the Sun’s. They have approximately the same mass, which means they have an astonishing density of about 1 tonne per cubic centimetre. After billions of years, white dwarfs will cool down to a point where they stop emitting visible light, transforming into so-called black dwarfs.

The first white dwarf that was discovered was 40 Eridani A. It is a bright celestial body 16.2 light-years from Earth, surrounded by a binary system consisting of the white dwarf 40 Eridani B and the red dwarf 40 Eridani C. Since its discovery in 1783, astronomers have tried to learn more about white dwarfs in order to gain a deeper understanding of the evolutionary history of the Earth in the Milky Way.

These interstellar remnants have historically been difficult to study. However, the data researchers have collected in this recent study, which was published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, presents new findings regarding how the collapsed stars move.

How has the movement of white dwarfs been documented?

“Thanks to observations from the Gaia Space Telescope, we have, for the first time, managed to reveal the three-dimensional velocity distribution for the largest catalogue of white dwarfs to date. This gives us a detailed picture of their velocity structure with unparalleled detail,” explained Daniel Mikkola, Doctoral Student in Astronomy at Lund University.

The Gaia Space Telescope has allowed researchers to measure positions and velocities for about 1.5 billion stars. However, it has only been recently that have they been able to completely focus on the white dwarfs in the Solar neighbourhood.

“We have managed to map the white dwarfs’ velocities and movement patterns. Gaia revealed that there are two parallel sequences of white dwarfs when looking at their temperature and brightness. If we study these separately, we can see that they move in different ways, probably as a consequence of them having different masses and lifetimes,” said Mikkola.

What does this data mean?

The results can be utilised to develop new simulations and models to continue to map the history and development of the Milky Way. Through an increased knowledge of the white dwarfs, the researchers hope to be able to under cover a number of inquiries surrounding the birth of the Milky Way.

“This study is important because we learned more about the closest regions in our galaxy. The results are also interesting because our own star, the Sun, will one day turn into a white dwarf just like 97% of all stars in the Milky Way,” concluded Mikkola.

To keep up to date with our content, subscribe for updates on our digital publication and newsletter.