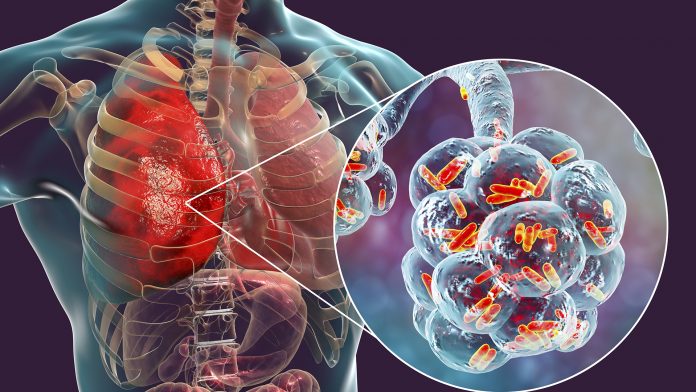

A research team from Hiroshima University has discovered a link between mycobacteria and red blood cells at lung infection sites.

What are mycobacteria?

Mycobacteria are a group of pathogenic bacteria that produce diseases, such as leprosy and tuberculosis, in humans. HU researchers have discovered an interaction between mycobacteria and red blood cells that, until now, has escaped scientific notice for 140 years since the discovery of the organism causing tuberculosis.

In 1882, Dr Robert Koch isolated the disease agent that causes tuberculosis (TB) – a mycobacteria later named Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This work validated Dr Jean-Antoine Villemin’s earlier evidence that tuberculosis was transmissible. While the use of streptomycin to treat TB would not be introduced for another 65 years, Koch’s discovery of the bacterial culprit essentially paved the way for its treatment.

M. tuberculosis, along with other mycobacteria, is implicated in lung disease and has been discovered to live in macrophages, which are white blood cells that engulf and kill pathogens. This bacterium is also found in blood and sputum coughed up by sick patients.

Associate Professor Yukiko Nishiuchi, lead author, explained: “Pathogenic mycobacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis (MAH), and Mycobacterium intracellulare, cause pulmonary infections as intracellular parasites of macrophages.”

Mycobacteria grow inside macrophages, and red blood cells, although also found in the sputum of tuberculosis patients, have not been specifically studied in disease progression.

This novel research was published on 16 March 2022 in Microbiology Spectrum.

What did researchers discover regarding the red blood cells?

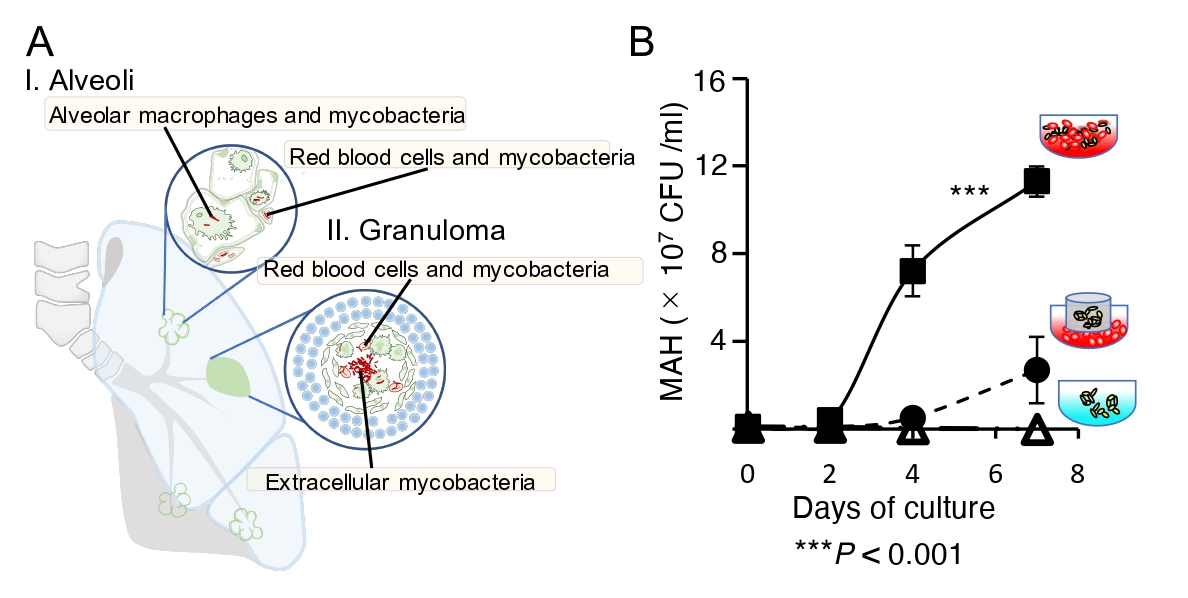

The researchers obtained lung tissue samples from five mice infected with two species of Mycobacteria – M. avium and M. intracellulare – as well as from a human patient with a MAH infection.

Microscopic examination revealed that the red blood cells were co-located with mycobacteria in both the capillary vessels and the granulomas – clumps of immune cells – of mice and human lung tissues.

To assess the existing relationship between the mycobacteria to human red blood cells, the scientists monitored their growth with and without the blood cells. They discovered that MAH grew more in the presence of red blood cells – they multiplied at a rate dependent on blood cell concentration, and their exponential growth was even faster than the growth of MAH inside macrophages.

“These results demonstrate that the erythrocytes promoted the vigorous growth of MAH,” said Nishiuchi.

Additionally, the study discovered that macrophages, typically targeted as parasitic hosts by mycobacteria, preferentially engulfed red blood cells with MAH attached. The binding of the MAH to red blood cells may have resulted in the release of energy in the form of ATP, which then stimulated macrophages to engulf the infected cells.

A. Mycobacteria coexist with red blood cells in capillary vessels and in granulomas, exist within macrophages as well.

B. Mycobacteria actively proliferate when they can adhere directly to red blood cells (square).

Photo Credit: Yukiko Nishiuchi.

How can this be applied to human healthcare?

The results revealed that pathogenic mycobacteria attach to human red blood cells, and then capitalise on their relationship to multiply. This bacterium had previously been discovered outside macrophages at infection sites. However, these results suggest that the presence of those extracellular mycobacteria may be a result of the relationship with red blood cells.

Furthermore, while red blood cells are best known for their role in transporting oxygen between lungs and tissues, they also play two important roles in mycobacterial infections. They play a defensive role against infections by capturing pathogens and then transferring them to the macrophages in the liver and spleen, where they are then eliminated. This study reveals that red blood cells may also get targeted as host cells for mycobacteria.

Thus, how these roles unfold might determine the outcome of an infection. This is because, if the red blood cells’ defence role is going well, the mycobacterial disease is regulated. However, red blood cells overwhelmed by an attack of mycobacteria may help them spread throughout the body.

What do these results mean regarding future applications?

Researchers intend to identify the adhesion factor on the bacteria that allows it to stick to red blood cells. The sticking mechanism may reveal how the mycobacteria, usually parasitic inside macrophages, can also grow outside of cells. Thus, their goal is to contribute to the development of new therapies by better understanding how pathogenic mycobacteria navigate host defence systems to spread.

“Our research will change the conventional common sense that ‘mycobacteria grow intracellularly,’’’ concluded Nishiuchi.

To keep up to date with our content, subscribe for updates on our digital publication and newsletter.