A discovery algorithm, designed to uncover near-Earth asteroids for the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s upcoming ten-year night sky survey, has identified its first potentially hazardous asteroid.

A hazardous asteroid is a celestial object that astronomers prefer to keep an eye on due to their potential risks to our planet.

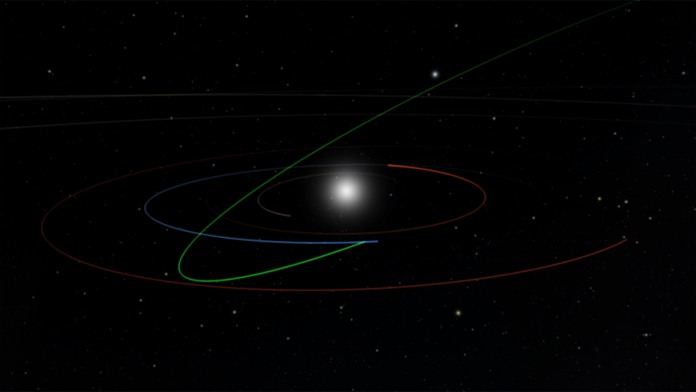

The roughly 600-foot-long asteroid, designated 2022 SF289, was discovered during a test drive of the algorithm with the ATLAS survey in Hawaii.

So far, it poses no risk to Earth for the foreseeable future and confirms that the next-generation algorithm, known as HelioLinc3D, can identify near-Earth asteroids with fewer and more dispersed observations than current methods.

Ari Heinze, the principal developer of HelioLinc3D and a researcher at the University of Washington, explained: “By demonstrating the real-world effectiveness of the software that Rubin will use to look for thousands of yet-unknown potentially hazardous asteroids, the discovery of 2022 SF289 makes us all safer.”

Could hazardous asteroids destroy our planet?

Our Solar System is home to tens of millions of rocky bodies, ranging from small asteroids to dwarf planets larger than the Moon.

Most of these celestial bodies are distant; however, some orbit close to Earth and are known as near-Earth objects (NEOs). Potentially hazardous asteroids are the nearest, located within around five million miles of Earth’s orbit.

These hazardous asteroids are systematically searched for and monitored to ensure they won’t collide with Earth, a potentially devastating event.

Vera C. Rubin: Joining the hunt for hazardous objects

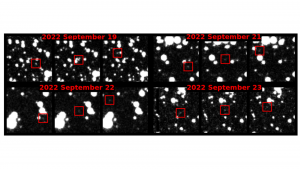

Scientists search for potentially hazardous asteroids (PHAs) using specialised telescopes that take images of parts of the sky around four times a night.

A discovery is made when they notice a point of light moving unambiguously in a straight line over the image series. Scientists have discovered about 2,350 PHAs using this method, but estimate that at least as many more await discovery.

From its peak in the Chilean Andes, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is set to join the hunt for these objects in early 2025.

Rubin’s observations will dramatically increase the discovery rate of hazardous objects with its 8.4-metre mirror and 3,200-megapixel camera. It can also visit spots in the sky twice per night rather than the four times needed by present telescopes.

However, with this novel observing cadence, researchers need a new discovery algorithm to spot space rocks reliably.

How does the new algorithm work?

Rubin’s solar system software team at the University of Washington’s DiRAC Institute has been working to develop such codes.

Researchers have now developed HelioLinc3D, a code that could find potentially hazardous asteroids in Rubin’s dataset.

With Rubin still under construction, HelioLinc3D is being tested to see if it could discover a new asteroid in existing data, with too few observations to be discovered by today’s conventional algorithms.

Astronomers at the ATLAS survey offered their data for testing, and the dataset discovered its first hazardous asteroid, 2022 SF289, on 18 July. 2022 SF289 was observed at a distance of 13 million miles from Earth.

“Any survey will have difficulty discovering objects like 2022 SF289 that are near its sensitivity limit, but HelioLinc3D shows that it is possible to recover these faint objects as long as they are visible over several nights,” said Larry Denneau, one of the lead astronomers at ATLAS.

“This is just a small taste of what to expect with the Rubin Observatory in less than two years when HelioLinc3D will be discovering an object like this every night,” added Rubin scientist Mario Jurić, director of the DiRAC Institute, professor of astronomy at the University of Washington and leader of the team behind HelioLinc3D.

Jurić concluded: “More broadly, it’s a preview of the coming era of data-intensive astronomy. From HelioLinc3D to AI-assisted codes, the next decade of hazardous asteroid discoveries will be a story of algorithm advancement as much as in new, large telescopes.”