Marine life in the deep ocean can take decades to recover from the impact of deep sea mining for rare metals, new research shows.

The study found that the site of a deep sea mining test in 1979 in the North Pacific still showed lower levels of biodiversity than neighbouring undisturbed sites 44 years later.

The research was conducted in 2023 and 2024 5,000m below the surface in the Pacific Ocean in the Clarion–Clipperton zone. This is roughly halfway between Mexico and Hawaii and is a vast, flat and deep region of the ocean floor known as an ‘abyssal plain.’

The partners are part of Seabed Mining and Resilience to Experimental Impact (SMARTEX), a research project funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council.

SMARTEX was set up to determine the ecological impact in the central Pacific Ocean of deep sea mining for mineral deposits known as nodules that contain rare metals like cobalt, manganese and nickel, which are critical elements in electric car batteries and other electronic devices.

Quantifying the unknown impacts of deep sea mining

The researchers analysed how deep sea organisms are affected by sediment exposure and associated stress to help quantify the less obvious impacts of deep sea mining.

As part of this, they developed a procedure to measure how mining could damage the DNA of deep-sea fish.

Dr Mark Hartl, a marine biologist at Heriot-Watt University and co-author of the study, explained: “These nodules are potato-sized mineral deposits that have built up in layers over thousands of years. Mining companies want to mine these for critical metals like cobalt and nickel.

“But there are so many unanswered questions. For example, we know that the nodules produce oxygen. If they’re removed, will that reduce the amount of oxygen in the deep sea and affect the organisms that live there?”

Long-term impacts of mining the sea bed

More than 21 billion tonnes of nodules are estimated to lie on the seabed of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, which spans more than 6 million square kilometres – about 25 times the size of the UK.

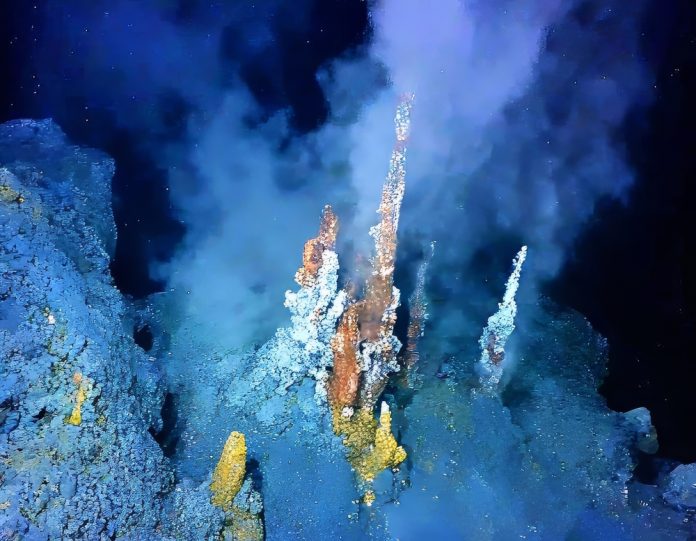

These nodule fields sustain “highly specialised animal and microbial communities,” the researchers say. These include giant single-celled organisms with chalky shells (called ‘foraminifera’), highly specialised sea cucumbers and fish, and many species that rely on the nodules as the only hard surface to settle on.

The researchers studied an area on the ocean floor where a 14-metre-long experimental deep sea mining machine was deployed in March 1979. This mined an unknown quantity of nodules over the four days, using a mechanical rotating seabed rake that picked up nodules and transferred them via a conveyor to a crusher.

The scientists conclude that, four decades after this mining test, “the biological impacts in many groups of organisms are persistent,” although some species have started to recover.

The physical signs of the test are also still visible, including areas of the seabed that have been stripped of nodules and visible track marks from the mining vehicle.

Can marine ecosystems ever recover?

Deep sea mining is currently prohibited under an international moratorium while the International Seabed Authority (ISA) develops the legal, financial, and environmental framework to underpin any potential full commercial exploitation when it occurs.

A key question in this decision is whether deep-sea ecosystems can recover from mining disturbances, the National Oceanography Centre says.

It adds that deep sea mining is increasingly being considered as a potential solution to supply the crucial metals required for advancing global technology and driving the transition to a net-zero energy future.

The researchers concluded that nodule mining is expected to cause “immediate impacts” to the seabed surface and habitat in the path of collector vehicles. This includes mechanical disturbance, including the removal of hard surface spaces for species to live below the seabed and the compacting of sediment.

Another impact is the creation of sediment plumes, which could have “significant impacts on ecosystems” beyond the immediate mined areas, the researchers say.