Researchers have developed a new method to efficiently remove up to 80% of dye pollutants from contaminated water.

The team, led by experts at Chalmers University of Technology, purified contaminated water using a cellulose-based material. This development can potentially combat the widespread problem of toxic dye discharge from the textile industry.

Moreover, it could help developing countries with poor water treatment technologies. An article, ‘Cellulose Nanocrystals Derived from Microcrystalline Cellulose for Selective Removal of Janus Green Azo Dye,’ was published in Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research to detail the advantages of this technology.

Many people are living without access to clean water

Clean water is necessary for our health and living environment; however, it is far from accessible to everyone. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over two billion people are forced to use contaminated water sources.

Building upon the importance of clean water access, the Chalmers team focused on new uses for cellulose and wood-based products. The group, led by Gunnar Westman, Associate Professor of Organic Chemistry at Chalmers, developed technology that can easily remove water pollutants.

The researchers have built up solid knowledge about cellulose nanocrystals – this is where the key to water purification lies. These tiny nanoparticles have an outstanding adsorption capacity, and researchers have now found a way to utilise these in contaminated water.

“We have taken a unique holistic approach to these cellulose nanocrystals, examining their properties and potential applications. We have now created a biobased material, a form of cellulose powder with excellent purification properties that we can adapt and modify depending on the types of pollutants to be removed,” said Westman.

Breaking down toxins with cellulose-based technology

In their study, the researchers showed how toxic chemicals can be filtered out of contaminated water using cellulose and wood-based materials. They conducted the research in collaboration with the Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur in India, where dye pollutants in textile industry wastewater are a widespread problem.

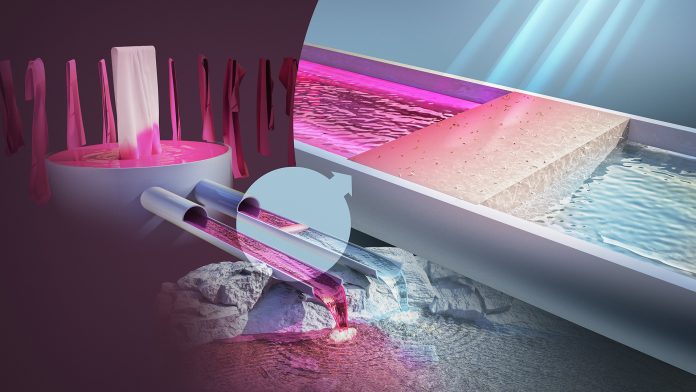

The method does not require pressure or heat, and uses sunlight to catalyse the process. Westman explained that the technique can be likened to “pouring raspberry juice into a glass with grains of rice, which soak up the juice and make the rice transparent.”

Westman continued: “Imagine a simple purification system, like a portable box connected to the sewage pipe. The pollutants are absorbed as the contaminated water passes through the cellulose powder filter, and the sunlight entering the treatment system causes them to break down quickly and efficiently.

“It is a cost-effective and simple system to set up and use, and we see that it could be of great benefit in countries that currently have poor or non-existent treatments for contaminated water.”

Testing the method in developing countries: Can it depollute contaminated water?

India is a country with extensive textile production, meaning large amounts of dyes are released into lakes, rivers, and streams every year. Contaminated water contains dyes and heavy metals and can cause skin damage with direct contact and increase the risk of cancer and organ damage when they enter the food chain. Additionally, nature is affected in several ways, including impairing photosynthesis and plant growth.

Therefore, the researchers decided to test their technology in India, as conducting field studies is an essential step in testing the method’s feasibility. So far, laboratory tests with industrial water have shown that more than 80% of the dye pollutants are removed with the new method. Westman sees good opportunities to increase the degree of purification further.

He explained: “Going from discharging completely untreated water to removing 80% of the pollutants from contaminated water is a vast improvement and means significantly less destruction of nature and harm to humans.

“In addition, by optimising the pH and treatment time, we see an opportunity to improve the process further to produce both irrigation and drinking water. It would be fantastic to help these industries get a water treatment system that works so that people in the surrounding area can use it without risking their health.”

Opportunities for other water pollutants

Westman also sees great opportunities to use cellulose nanocrystals for the treatment of other causes of water contamination, not just dyes.

In a previous study, the research group showed that pollutants of toxic hexavalent chromium, common in wastewater from mining, leather, and metal industries, could be successfully removed with a similar type of cellulose-based material. The group is also exploring how the research area can contribute to the purification of antibiotic residues.

“This material has great potential to find good water purification opportunities. In addition to the basic knowledge we have built up at Chalmers, an important key to success is the collective expertise available at the Wallenberg Wood Science Center,” Westman concluded.