As the space environment becomes ever more intrinsic to the way we live our lives, Northern Space and Security Limited explains how we can safeguard it for the future and be committed to space sustainability.

Space, or more specifically the region of space humankind uses on a day-to-day basis out to just beyond the GEO-stationary belt (approximately 36,000km away), is a complex and hazardous environment but one which provides modern life with significant benefits. Without question, humanity has become increasingly reliant on space; economically, politically, militarily, and socially, resulting in the importance of space sustainability. Orbiting satellites support a myriad of services, from providing a timing signal for many services including finance, energy, and transport (to name just a few), long-range weather forecasting, monitoring the environment, TV and communications, and so much more. But is it forever? Believe it or not, near-Earth space is a finite resource, and it is both politically and commercially contested.

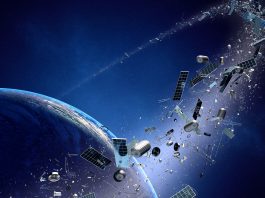

Although it is a natural resource available for all, and despite access to it being limited predominantly to those with a launch capability, we are at risk of over-populating specific altitudes of orbit and increasing the risk of space debris generating events. Space debris poses an ever-increasing hazard to the benefits from space we have grown accustomed to, as it risks the safe operation of satellites in orbit. The sky is not falling in yet but, unless we address the issues created through human activity in space, we risk losing access to a resource that provides significant benefits to humanity.

Tackling space debris

Space debris from the last 64 years of space operations poses a hazard to space operators and significantly threatens the long-term sustainability of the environment humanity has unwittingly become reliant upon. Uncontrolled objects as small as 1cm travelling much faster than a speeding bullet, at approximately 7km per second, can cause a significant amount of damage to operational satellites. At the very least, the threat of an in-orbit collision could cause operators to manoeuvre their satellite for safety, expending crucial fuel and reducing the length of the mission, or a collision could damage sensors and antennas on board a satellite, thus limiting mission effectiveness.

Ultimately, a collision with larger space objects could destroy a satellite and create more orbital debris, which may remain in orbit for decades, if not centuries. The larger the uncontrolled object, the greater the damage, and of course, any collision between orbiting objects creates a cloud of debris which can spread across a significant number of other orbital planes over time, as recently demonstrated when Russia conducted an anti-satellite missile test on 15 November 2021. The first-ever recorded collision between an active and a defunct satellite in February 2009 (Iridium and Cosmos satellites) created a debris cloud of more than 2,000 observable pieces, and most of those pieces of debris remain in orbit today, almost 13 years later.

It should be noted that most of the space surveillance and tracking sensors are generally only capable of tracking objects no smaller than 10cm in size – about the size of a soft drink can. Historically, these sensors have been operated by the military, and their primary mission is for tracking missiles, not satellites or smaller objects. Their capability is optimised for larger objects in space and further limited by the mission requirements and the perception of greater threats, not for sustaining space operations. An event such as the Iridium-Cosmos collision mentioned above would probably create thousands of pieces of debris that are not being tracked, therefore creating an unseen hazard to safe satellite operations. The presence of space debris poses a continuous threat to operational satellites and long-term sustainability of the orbits they transit. At its very worst, significant debris ‘clouds’ could create a cascading effect where debris collides with more objects in orbit, creating more debris and rendering certain orbital planes unusable. There are few sensors capable of detecting and tracking such clouds. Is it time to prioritise new methods to support space sustainability?

Tackling space debris is currently the focus of several national space agencies, commercial entities, and academic institutions. However, it has been discussed at length across the space community for well over a decade with little being done. As the potential extent of the problem is being realised, there has been greater interest in using active removal techniques to mitigate the risk of large objects colliding on orbit but little investment in improving the ability to track, predict, and understand the full extent of the problem of how big the orbital population is. In recent years, we have seen the emergence of companies focusing on active debris removal. A number of conceptual and demonstration missions have been planned and executed alongside a growing interest in servicing and refuelling resident space objects also. But these missions include placing additional objects on orbit without fully understanding the extent of the problem.

Additionally, there is little or no incentive nor business case for the active removal of defunct satellites, nor larger pieces of debris currently. The few agencies and organisations investigating the concept are still at the preliminary stages of research and development. Ultimately, the key to both the success of active debris removal missions and long-term sustainability for the benefits from space, lies with truly understanding the extent of the problem and how close we are to the cliff edge.

Understanding what is happening on orbit, what goes into and comes out of space, and space weather activity is known as Space Situational Awareness (SSA). Until the last decade, it has predominantly been the responsibility of the US Government, through military capabilities, to develop SSA, and provide satellite operators safety of flight support. However, over the last ten years, we have seen an ‘explosion’ of commercial entities providing SSA as a service, both to governments and commercial satellite operators. These commercial companies do not have the traditional governmental ties nor budgetary limitations, bureaucratic ‘anchors’, nor general career models that can hinder flexible and rapid response to the developing hazards in orbit. Commercial space is more able to respond to the needs of the global space industries and rapidly changing space operating environment.

Expertise in SSA does not come quickly nor easily. The government/military career model traditionally does not support long-term dedication to a single practice. Additionally, one could also argue that it is not the responsibility of the military to ensure space sustainability; their focus should be space security. Individuals with less than a decade of experience in the art of SSA, although able to apply the theory, will probably struggle when describing space conditions important to space sustainability. Commercial entities are ‘in the business’ of developing and retaining the experience necessary to understand the long-term requirements of civil, commercial, and military space. Alongside academic research, this expertise is essential to framing and appreciating the problem and developing solutions to ensuring that the benefits of space are available long into the future, finding the necessary answers to a developing and significant environmental problem.

Northern Space & Security Ltd (NORSS) is the UK’s only commercial company dedicated solely to SSA, possessing an unprecedented level of experience in the field. Collectively, the key partners – Ralph ‘Dinz’ Dinsley, Sean Goldsbrough, and Dr Adam E White – have more than 50 years of SSA experience from across government, academic, commercial, and military space, and are dedicated to developing that experience and expertise across their team of young, bright engineers. NORSS is leading the charge to balance education and experience across its team to tackle the current problems within SSA and to help the UK lead in future sustainable practices to ensure the benefits from space continue long into the future. The company supports several contracts with the UK Government providing technical experience for space surveillance and tracking, space safety and regulation alongside the development of a commercial operations centre to support academic and commercial space requirements.

Based in the North East of England, NORSS are harnessing their collective expertise to become world-leading providers in SSA information. In just four years, they have grown from an SSA consultancy to become the UK’s premier end-to-end provider of information on objects in near-Earth orbit. From its LEO Optical Camera Installation (LOCI) system, supported at Kielder Observatory, collecting data on objects in low-Earth orbit to the processing and distribution of a finished product, NORSS is leading the way in developing the necessary experience in the UK to support the long-term sustainability of space operations. NORSS ensures the necessary experience will be developed for now and to support the future.

With a global reach and a range of international collaborators, Dinz, Adam, Sean and the team are bringing both experience and innovation to help users of space truly understand the performance of their assets. NORSS is the only company in the UK with an Orbital Analyst apprenticeship to ensure understanding begins early and develops rapidly. As companies, academics and the defence sector become ever more reliant on space, NORSS provides unparalleled levels of analysis on every aspect of the orbital environment. Given the significant number of technical resources and analytical insight within NORSS, the company supports its commitment with the promise that: “If it is up there, we will find it.”

You can find more about NORSS in their video entitled ‘We Are Northern Space and Security Limited’.

Please note, this article will also appear in the eighth edition of our quarterly publication.