A research team from the Dresden University of Technology (DUT) has identified proteins to utilise in a novel immunotherapy for colon cancer.

How is this immunotherapy different regarding treatment for colon cancer?

Colon cancer is one of the most common types of cancer. In advanced stages of the disease, treatment continues to rely significantly on traditional chemotherapy. The new generation of cancer treatments, known as immunotherapies, has only been effective in a small subgroup of colon cancers.

In response to this, DUT scientists – led by Professor Sebastian Zeissig – have identified proteins that are promising for new immunotherapy colon cancer treatments. Their results also underline the central role of intestinal bacteria in the development of colon cancer.

This study was published in the journal Immunity on 31 March 2022.

How does cancer form in the body?

Our bodies are capable of naturally clearing cancerous cells – the immune system typically detects mutated cells in our body and destroys them. However, on occasion, cancerous cells can discover a way to remain undetected from the immune system.

The cells then develop molecular signals that block immune cells from recognising them as a threat. This, among other strategies, allows cancer cells to multiply and grow into tumours. Understanding the molecular mechanism of this process has resulted in the development of new cancer treatments, called immunotherapies. These treatments encourage the patient’s immune system to target the tumour and limit its growth.

Unfortunately, current immunotherapies are not effective for all types of cancers – most cases of colon cancer do not respond to these treatments. However, researchers from DUT have described a new pathway that lets colon cancer hide from the immune system. Their results provide a potential first step towards the development of a new generation of immunotherapies.

How is this ‘new’ colon cancer avoiding immunotherapies?

Inhibition of immune cells is conducted by special signals present on the surface of cancer cells. “These signals are known as checkpoint proteins,” explained Professor Sebastian Zeissig, leader of the study, from the University Hospital Dresden and the Centre for Regenerative Therapies Dresden (CRTD) at DUT.

Current immunotherapies utilise drugs called ‘checkpoint inhibitors,’ to target a small set of known checkpoint proteins. Unfortunately, this approach had a limited impact on colon cancer growth.

“This raised the question of whether there are other checkpoint proteins that may represent more promising targets for immunotherapy in colon cancer,” noted Dr Kenneth Peuker, author of the study.

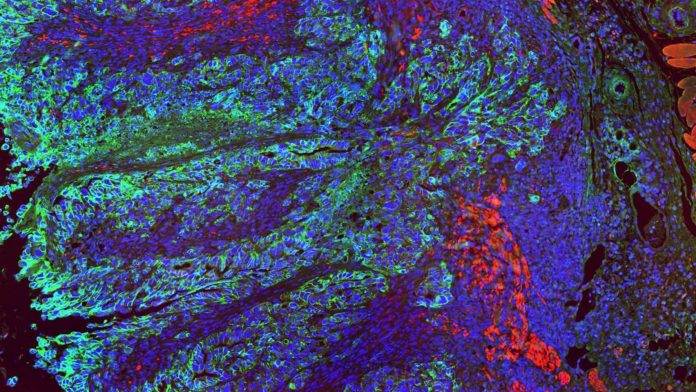

Researchers analysed colon cancer samples and investigated the signal proteins present in tumour cells, but not in the healthy tissue. Two proteins were considered note-worthy in this observation: CB7H3 and B7H4. Both were present in large numbers in colon cancer cells, while almost undetectable in the healthy tissue.

“We decided to block B7H3 and B7H4 in colon cancer cells,” added Dr Peuker. “The result was startling. Tumour tissue, in which these signals were disabled showed significantly slowed growth or even shrinking. We have observed that now the immune cells could invade the cancer tissue and started to control tumours cells.”

Additional tests confirmed that the B7H3 and B7H4 proteins are indeed working as checkpoint proteins. “Blocking these signals suddenly allowed immune system to attack tumours cells,” noted Professor Zeissig.

Scientists discovered B7H3 and B7H4 to be present, not only in the primary colon cancer tumours, but also in their metastases in the liver. Disabling these proteins slowed the growth of the primary tumours as well as their liver metastases – researchers observed that some of the treated mice survived long-term despite having metastatic tumours.

© Priyanka Oberoi

How was this ‘new’ immunotherapy treatment established?

The team characterised a broad cascade of events that permits colon cancer to develop its ability to block immune cells. They were able to demonstrate that breaking the intestinal barrier is a crucial step in the process. When the intestinal barrier breaks at sites of tumours development, bacteria that are normally present in the intestine can suddenly enter the surrounding tissue.

This is considered an important early event in the development of colon cancer. Now, the DUT team can demonstrate that these bacterial runaways serve as an initial trigger for the colon cancer cells to hide from the immune system.

“We found that cells present in the tissue can detect the invading bacteria. This, in turn, activates a full cascade of steps. The resulting molecular communication between the cells eventually leads the cancer cells to project B7H3 and B7H4 on their surface and hide from the immune system,” said Dr Peuker.

The team determined that utilising broad-spectrum antibiotics to destroy the invading intestinal bacteria also reduced the tumour size and decreased the extent of liver metastases. “Our results provide a new link between microbiota and tumour growth in colon cancer. We would like to focus more on this angle in the future,” added Professor Zeissig.

What does this mean for healthcare?

The results of the new study come predominantly from research in mice, however they offer a promising outlook for future cancer therapies for humans.

“Our analyses of human samples showed that B7H3 and B7H4 are also present in human colon cancer cells and that their presence correlates with poorer outcomes of colon cancer patients. These proteins are also barely detectable in healthy tissues in humans which suggests that their targeting may be safe,” concluded Professor Zeissig.

“We hope that our work will serve as a foundation for new studies that address the efficacy of targeting of B7H3 and B7H4 in human colon cancer in the future.”

To keep up to date with our content, subscribe for updates on our digital publication and newsletter.