As global demand for rare earth elements increases, global resources must be efficiently explored and utilised to ensure a secure rare earth supply chain.

Whilst the rare earth mining sector is one of the most in-demand and fast-growing industries in the world, it is also one of the least publicised.

This class of metals, which sits at the bottom of the periodic table and is categorised as ‘rare earths’, is made up of 17 elements used in a vast array of industries and in technologies that are commonly used end-product items. However, it is a subset of these elements, known as the ‘critical metals’ – those used in the production of permanent magnets – which are most in demand. These metals represent only 20% of the total rare earths consumed but 80% of the value. They are vital to many high-tech applications, especially in renewable energy.

The market for rare earths

To provide greater explanation, we must look at the individual prices of the metals. Those used in glass polishing and ceramics, for example, cost only dollars per kilo, whereas the critical metals – neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), dysprosium (Dy) and terbium (Tb) – now have prices ranging from hundreds of dollars to thousands of dollars per kilo. These prices have been soaring over the past decade and are set to increase further as demand, coupled with supply chain issues, increases.

The wider market context can help us understand these extraordinary prices. We need to look at the growth of electric vehicles (EVs) and the global roadmap for replacing traditional energy sources with sustainable renewable energy (in the form of wind turbines). At last November’s COP26 Summit, world leaders set out a timeframe to remove internal combustion engines from the car production line. Some countries, including the UK, elected as short a timeframe as 2030, placing an impressive yet heavy burden on car manufacturers, and crucially an even greater burden on their supply chains.

At the heart of all EVs are two key components, the battery and the electric motor drivetrain. It is in the drivetrain where you will find rare earths. Each EV requires kilos of rare earths to make a magnet powerful enough to power the drivetrain which propels a vehicle. Similarly with wind turbines, an 80-metre turbine requires hundreds of kilos of critical metals to produce the permanent-magnet synchronous generators. There is also an additional benefit from using rare earths in wind turbines in that the power units they create require very little maintenance, making them ideal for offshore wind farms where regular access is almost impossible and is cost prohibitive.

EV sales boomed in 2021, despite the pandemic, with almost two million new cars registered around the world, taking the total to over ten million vehicles. Sales of EVs in the UK in 2021 increased by 180% over 2020, and almost 20% of new UK sales so far in 2022 are EVs or hybrids. By 2050, the number of EVs on the road is expected to be over 700 million vehicles, accounting for over 60% of all cars, globally. For the foreseeable future, there is no alternative to rare earths to perform these crucial functions.

Meeting the global challenges

It is becoming increasingly clear that, as well as having a crucial role to play in the manufacture of certain high-tech devices, the supply of rare earths is also strategically necessary for nations. A serious impediment to becoming energy independent, through growing renewable capacity, is a restriction on the supply of critical metals required for wind turbines and EVs. With global capacity for processing of rare earths located mostly in China, there is, however, the potential for major supply disruption if any such problem occurs with this one source.

Traditional hydrocarbon resources are frequently found in countries with difficult governing regimes, but, for the end user, there is at least the option of choosing its supplier, as producers are spread out across several countries around the world. In the case of rare earths, however, China takes on this mantle by itself and is the de facto equivalent in the oil industry of Russia, the US, China, and the Middle East, all rolled into one.

It has not yet fully dawned on governments around the world that, with the need for increased renewable energy investment, this almost total dependence on China has become a potentially very serious risk. The solution is investment in new rare earth processing facilities, which must happen now as capacity cannot be built overnight. The world is already experiencing a global shortage of NdPr by some thousands of tonnes per year.

There is a strong argument that this infrastructure investment should have happened already, but lack of education about the key strategic uses of rare earths means it has not. For now, all we can do is stay hopeful that a major supply problem does not occur, whilst encouraging our governments to take this issue seriously and act immediately.

Altona Rare Earths

Altona Rare Earths Plc, listed on the London Stock Exchange, is the latest UK-based mining exploration company looking to carve a path into this essential and valuable sector. The company is run by a board of mining and business professionals who are based in both the UK and Africa, the latter being where the company’s mining assets are located.

Altona has a simple and clear strategy; to acquire controlling interests in overlooked or neglected mining tenements which have reported the presence of rare earth metals at some point over the past 30 years, but which have not been extracted. The reason that there are many of these ‘overlooked’ rare earth assets in Africa is because, around 10-15 years ago, there was not the global demand that there is today. Many mining companies, while looking for other minerals, only discovered rare earths ‘by accident’ and, while the data was gathered, there was never a viable need to move to production. The current change in global demand for rare earths has now benefited Altona and other rare earth exploration companies.

The company’s Chief Operating Officer and Head Geologist, Cedric Simonet, a French national who has lived and worked in Africa for the past 25 years, has a unique talent in identifying projects such as these.

Simonet commented: “Africa is the perfect breeding ground for these critical elements. The geological formations caused by the shift in tectonic plates along the 4,000-mile-long East Rift Valley, which runs down the Eastern side of Africa, has caused outcroppings of carbonatites on a vast scale, many of which have experienced heavy weathering over the millennia, providing highly concentrated areas of rare earths that can be mined in economically viable amounts.”

Understanding the rare earth supply chain

This leads us to ask, why are these elements called rare earths and just how ‘rare’ are they really? The answer is intriguing, as rare earths are actually among the most abundant metals captured within the Earth’s crust, but the skill of the mining company is to find ‘pockets’ that are sufficiently concentrated so that their extraction remains profitable.

This, in turn, leads us back to look at the price of each metal in a mining context as, for a company like Altona, the cost of mining the cheapest metals, such as cerium, could be cost prohibitive, but the extraction of NdPr, even in small quantities, could establish Altona as a leading player in the rare earths global supply chain.

Altona’s Chief Executive, Christian Taylor-Wilkinson, commented: “The main goal of Altona is to become part of the global rare earths supply chain in under three years and to help provide an alternative source of critical metals, thereby removing the current strangle-hold which China has enjoyed in the rare earths market for the past 15 years.

“The magnet metals, predominantly NdPr, are the holy grail for rare earths miners in this current evolution of the industry. First and foremost, we are looking for these specific metals but, if the projects we are currently operating indicate strong signs of becoming ‘general basket’ assets, we will not overlook the other 13 elements, as their requirement in such a multitude of uses could prove profitable.”

Altona’s Chief Executive raises a valuable point in terms of China’s dominance in the rare earths market. Due to various favouring factors in the late 1990s, China was able to steal a march on the competition and price other major producers out of the market. The rise of China’s middle classes in the early 2000s, with their demand for consumer goods and new housing, forced the Chinese Government to retain many metals for their own consumption. This, combined with an abundance of high-grade, heavy rare earth mines, allowed China to become the producer of over 80% of the world’s rare earth supply chain. More importantly, as China still remains the only major processor of rare earths, it controls approximately 95% of the world’s supply.

Naturally, these statistics are cause for concern for the other major economic powers around the world. Not only could China disrupt the much-desired phasing-out of combustion engines over the next 20 years, but, crucially, they have it in their power to squeeze supply to those industries, such as the military and defence sectors, thereby denying the US of its ability to build fighter jets, nuclear submarines, lasers, and missile systems.

At a time of heightened global sensitivities due to the conflict in Ukraine, these matters are weighing heavily on the governments of the world, leading the US to begin stockpiling rare earths. This has led to the current record prices we are seeing across the board.

What we expect to see over the next five years, now that the world is waking up to this crisis, is a number of processing facilities being built outside China, to receive those rare earths which have been extracted in the likes of Africa, the US, Australia, and South America. Only by establishing a long-term and sustainable supply chain outside China, which Altona is driving to become a leading part of, can self-sufficiency be attained in those industries that are crucial to our onward development.

Altona came to this realisation in 2020 and commenced an intensive programme of unearthing suitable deposits of high-grade rare earths across a number of African jurisdictions, completing its first acquisition, in Mozambique, in July 2021.

Christian Taylor-Wilkinson said: “Understanding both the nature of the rare earths sector and the UK investment market, we have created a strategy which allows us to continuously move forward. We are achieving this by taking ownership of multiple projects at varying stages of development and by providing frequent updates on our project advancements so we can keep our shareholders informed and educated.”

The Monte Muambe Rare Earths Project

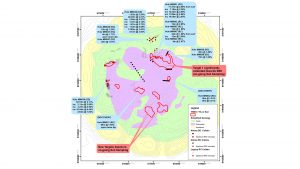

The Monte Muambe Rare Earths Project, Altona’s first asset, is a 4km2 carbonatite intrusion, formed in an extinct volcano holding appreciable quantities of rare earths at an above-average level for Africa. The company commenced its Phase 1 exploration drilling in Q3 2021, where it drilled over 40 holes for a total meterage of 3,000m. The programme discovered two new target areas with an average Total Rare Earths Oxide (TREO) of over 2%.

Altona is keen to keep the momentum flowing at its first project and it moved to the resource drilling phase in April 2022, which it expects to complete by year-end 2022, producing a Maiden Resource Estimate. The programme is expected to see a further 8,000m of drilling performed and it is expected to find new rare earth supply chain targets which can be taken to bankable feasibility study by 2025.

The company is confident that Monte Muambe could become a major resource for light rare earths, including NdPr, and Altona is keen to establish a value for the project as soon as possible.

In a highly competitive market, the company admits to having its failures in trying to find the right type of project, which fit in with its strict investment criteria.

Taylor-Wilkinson commented: “We have, to date, investigated several projects, at first inspection all of which looked to be solid assets – but, after performing a more in-depth study and having the benefit of the ‘nose’ of our in-country COO, we had to dismiss them either because the asset wasn’t what it initially appeared or we experienced difficulties with the local partner.

“We are seeing a lot of competition out there and Africa is in the midst of a land-grab mentality right now, due to the incredible macro-factors affecting the sector. Altona, however, remains well-placed to succeed in its mission. We have now completed a second acquisition in as many years and we hope to add our third project by year end 2022.”

Simonet continued: “Africa is blessed with two main types of rare earths deposits, the carbonatite hard-rock formation and the ionic-adsorption clay deposit, which are typically smaller but much easier to extract and process. To put things into context, China has an abundance of ionic-clay mines, hence their dominance of the rare earths market, particularly heavy rare earths. Importantly for Altona, it has been reported that China’s reserves will start to run low by 2028 and we are positioning ourselves to become a long-term alternative for end users.

“Altona is looking to build its portfolio around a blend of these two geological formations, providing us with large, long-term but high-value assets and smaller, quick-to-market but equally valuable ionic-clay assets. We believe this strategy makes us stand out from an investor point of view.”

Altona Rare Earth’s 2022 outlook

The team at Altona will be spending 2022 in a diverse number of activities – resource drilling at Monte Muambe, completing scout drilling at the new project site in Mozambique, exploring Angola, Tanzania, Uganda, and Burundi to find the next rare earth supply chain project, forming strong relations with local third-party partners – crucial to the success of any African mining project with – and securing funding partners for the next decade.

Taylor-Wilkinson concluded: “It is clear to us that the term ‘rare earths’ is not yet used in common parlance and it deserves far more exposure in the ‘everyday’. It is time for people to re-evaluate their relationship with them due to their impact in people’s daily lives, with their use in so many household products. For example, if you are reading this article, it will probably be on a mobile device or PC – both of which require rare earths to function. Without these devices, you would be reading this in a print magazine, which is, of course, made from wood pulp, which is then transported to your doorstep or corner shop using vehicles powered by hydrocarbons; all of which are bad for the planet.

“For Altona, we have a window of opportunity of approximately five years to reach our goal of becoming a major supplier of rare earths and we are committed with every fibre of our being to achieve this goal.”

Please note, this article will also appear in the tenth edition of our quarterly publication