Graphite exploration and development company Ceylon Graphite is working to rapidly increase graphite production in Sri Lanka and resecure the country’s place in the global graphite supply chain. The Innovation Platform spoke to the company’s CEO, Don Baxter, to find out more.

Once heralded as a leading global producer of vein graphite, Sri Lanka faced drastic changes in the 1970s when the graphite industry was nationalised, leading to the closure of all mines in the country by 1979. The industry was re-privatised in the early 1990s and the demand for graphite production has rapidly increased in recent decades. Given the rising demand for battery materials in the global energy transition, it is more important than ever for Sri Lanka to ramp up graphite production and to become a secure player in the global supply chain for batteries and electric vehicles (EVs).

One organisation helping to facilitate this is Ceylon Graphite, which focuses on the exploration and production of graphite in historic resource jurisdictions in Sri Lanka. With a land package constituting 121km2 grids containing historic vein graphite deposits, the organisation is well-positioned to contribute to securing a stable graphite supply chain. Currently, Ceylon Graphite has four exploration sites where some have already commenced development, with the others to follow soon.

To find out more about the history and development of graphite production in Sri Lanka, and Ceylon Graphite’s role in furthering production, The Innovation Platform spoke to CEO Don Baxter.

Can you outline the landscape for graphite mining and exploration in Sri Lanka? How has it developed and why is it so important to increase production now?

The existence of high-grade vein graphite in Sri Lanka has been known since 1675.

From 1869 to 1918, there were nearly 3,000 graphite pits (some of which were mechanised) and mines scattered across the southwest of the island. The highest historical production of 33,411 t in a single year was in 1962.

In 1971, the government nationalised the graphite mining industry, taking over all the large mines and establishing the Graphite Corporation in 1972 to manage the large mining operations at Bogala, Kahatagaha and Kolongaha, before mismanagement and corruption forced all mines to close down in 1979.

Learning from its mistakes, the government re-privatised the industry in 1991, with the Bogala operations purchased by Bogala Graphite Ltd. In the following year, the Kahatagaha mine was taken over by Kahatagaha Graphite Lanka Limited – a government-owned public limited liability company.

Now that the Sri Lankan economy is weak, the government is hungry for more graphite production to benefit from taxes, royalties, and employment, whilst its weakening currency has the impact of reducing our expected cost of operations.

We do not fear another government nationalisation as the government has already learnt its lesson from past experience and, in addition, its combined royalties of 7%, plus about 30% corporate taxes, gives its fair share already. Since we are focused on achieving production to provide the government with taxes and employment for its people, it is beneficial for us to grow sooner than later. Given the high-grade nature of Sri Lankan graphite veins, we expect to have gross margins of 70% at the low unprocessed graphite price of $2,000 per tonne, even after the high government royalties. Most other graphite mines are not even profitable at the unprocessed graphite price.

We have already been working in Sri Lanka for many years, allowing us to develop a strong relationship with the government and a strong social licence. This gives us a big head start over the competition.

What enables Sri Lanka to produce commercial quantities of vein graphite?

Sri Lanka can produce commercial quantities of vein graphite because of its grade and purity. The grade is over 90% carbon, which allows it to be directly shipped for processing. In other words, we do not need to develop a mill or tailings dam. We simply crush and ship the mineralisation for processing. Therefore, our expected margins are high after high taxes and royalties. We have ten mining prospects, each of which have the potential to produce 5,000 tonnes per year with low development capital requirements. With the closing of our recent financing, we expect to be able to generate sufficient cash flows from the first two mining prospects and then grow from internally generated cash flows from there.

But, given that there are over 3,000 historic graphite mining operations in Sri Lanka, our future growth from our first-mover advantage could be substantial.

What are the main obstacles to graphite production in Sri Lanka and how are you working to overcome these? Have societal issues, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, disrupted the battery supply chain?

The main obstacle for graphite production in Sri Lanka is perceived country risk now. Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, has said the country’s economy has “completely collapsed”, leaving it unable to pay for essentials such as oil imports. The country is now working with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to reach a deal, which would allow the country to focus on increasing the country’s exports and stabilising the economy. We do not expect the economic weakness in Sri Lanka to impact us negatively since we are part of the solution.

Though COVID-19 has impacted the entire world’s supply chains, they are no longer frozen, so shipments have simply slowed, not stopped. The world is getting used to things taking a little more time to be achieved.

The conflict in Ukraine has served to increase input commodity costs and inflation, but these cost escalations have been offset by a lower exchange rate. Furthermore, even if the exchange rate appreciates such that is does not offset escalating costs, we expect the price of graphite to increase to maintain our expected gross margins at the very least.

Is the mining infrastructure in Sri Lanka well positioned to keep up with the increasing demand for graphite to be used in batteries?

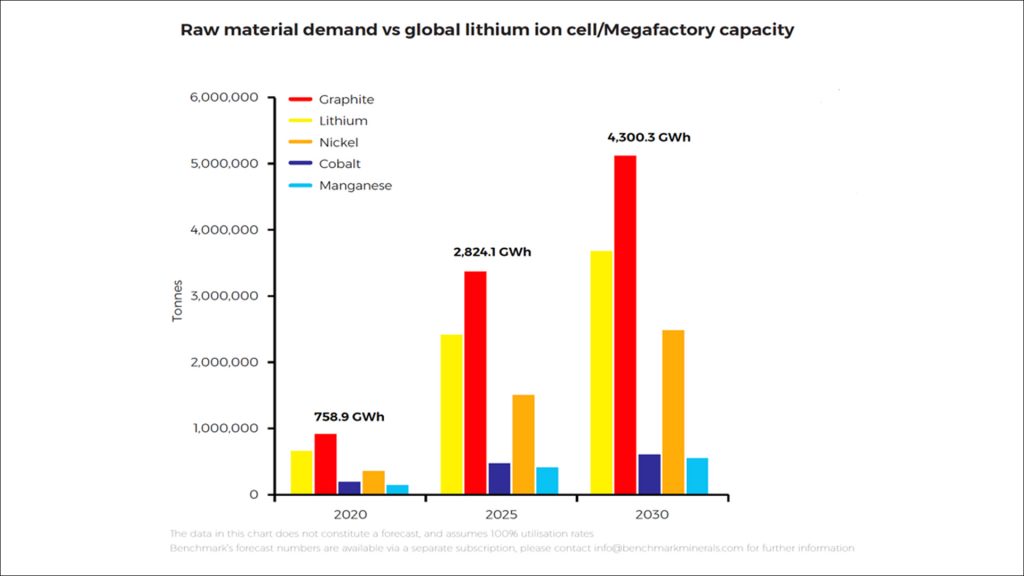

The mining industry in Sri Lanka is well positioned to benefit from increasing demand for processed graphite, but we will need hundreds of thousands of tonnes of graphite production to keep up with ever-increasing demand. As shown in the chart, the supply deficit for graphite is expected to continue to widen as far ahead as 2030, and its supply deficit is expected to be the greatest among other battery input materials.

Not only that, all graphite has to be processed to battery-grade graphite, for use in the anode. Ceylon will be able to grow out of free cash flows at the unprocessed graphite price. This will allow us to develop a processing facility from future free cash flows, or otherwise facilitate financing of a processing facility with a commitment from an end user. By adding a processing facility, we could increase our sales price from the unprocessed price of $2,000 per tonne to the battery-grade graphite price of $10,000 per tonne. There is ample supply of industrial graphite, but a growing shortage of processed graphite for the anodes of lithium-ion batteries. We believe that the world does not need more graphite, but it needs more processed graphite for batteries.

How important is collaboration in achieving a stable battery supply chain?

Collaboration is extremely important in achieving a stable battery supply chain. Governments, such as the UK, would need to secure a supply of graphite and other critical commodities, but they have limited ability to do so. Accordingly, each company is likely to solve their own problems on their own. The best financial programme for government assistance in developed democratic countries is to provide project loan guarantees to banks. But to benefit from this support, one typically needs a positive economic study and an offtake agreement from a strategic partner to qualify. Getting to that stage is the hardest part where there is little support. We are seeing the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) coming further up the supply chain, and we are having conversations that would not have happened a year ago.

What are the main goals for graphite production in Sri Lanka in the coming years and how do Ceylon’s own strategic goals align with this?

Sri Lanka envisions returning to its former glory of becoming the world’s top supplier of graphite. Ceylon intends to be the catalyst in this regard. Given the current state of Sri Lanka’s economy, sooner rather than later is the goal. This aligns with Ceylon’s aim of becoming the country’s largest graphite producer.