Axel Eggert, Director General of EUROFER, discusses the steel industry’s journey to decarbonisation and the challenges facing the transition.

As the world seeks to rapidly reduce its carbon emissions in the race to net zero, major industries across the globe are adopting greener processes to minimise their carbon footprint.

The steel industry, which currently produces more CO2 than any other heavy industry and comprises around 8% of total global emissions, is one of the sectors seeking to decarbonise its efforts by moving its production away from coal-fired furnaces to ones powered by electricity or hydrogen. This cleaner production process is commonly referred to as ‘green steel’.

The process of decarbonisation does have its challenges, however, including cost. To discuss more about the steel manufacturing industry’s journey to ‘green steel’ and the barriers in the way, The Innovation Platform spoke to Axel Eggert, Director General of the European Steel Association (EUROFER).

What is EUROFER and what are its key aims and objectives?

EUROFER was founded in 1976 and represents all steel producers in Europe. Its seat is in Brussels. Our members are both steel companies and national steel federations throughout the EU, with 500 sites across 22 countries directly employing 310,000 high-skilled people and generating an additional 2.2 million jobs indirectly and induced.

EUROFER therefore covers the entire spectrum of steel production in Europe, including both primary and secondary routes as well as carbon, stainless and speciality steel, with an average annual production of 153 million tonnes in total.

Our ultimate mission is to ensure the sustainable development of the steel sector in the European Union (EU). The EU’s very existence is built upon steel. The Schuman Declaration of 9 May 1950 established the European Community for Steel and Coal, which later became the European Union, providing over 70 years of peace and prosperity to our continent. EU steel will continue to do so as the primary building block of the climate neutral economy and society.

Many clean technologies, such as wind turbines and electric vehicles (EV), are reliant on steel. In this context, our top priority is to make the green steel transition a success whilst maintaining the European steel industry’s competitiveness in global markets. For this, access to affordable, abundant, and cost-competitive fossil-free energy is paramount.

As an EU association, we closely monitor EU and global policies that impact steel, including climate, energy, environment, trade, and access to raw materials, and provide advice to improve these. Additionally, we monitor the steel market by collecting and analysing data, and carrying out studies and research with the goal of improving the sustainability, resilience, and competitiveness of the European steel sector.

What role can steel play in creating a carbon-lean, circular, and environmentally responsible economy in Europe?

Steel is a vital component of almost all clean tech value chains, and if the EU is committed to achieving its Net-zero Industry Act, steel must be at the centre of its efforts. A circular, decarbonised and sustainable economy in Europe cannot be built without steel. Our estimates suggest that 74 million tonnes of additional steel will be required to meet the EU’s renewable energy targets.

Steelmakers are already the most significant recyclers in Europe, with a collection rate of 88%, the highest globally and of all materials, and 88 million tonnes of ferrous scrap recycled every year. As the steel sector continues to decarbonise, more and more steel production will be based on scrap recycling, further increasing this trend. Recycling a tonne of scrap saves 1.5 tonnes of CO2 emissions, and for stainless steel scrap, the figure rises to 4 tonnes. In this way, each year, the European steel industry saves 132 million tonnes of CO2, equivalent to the direct CO2 emissions of 82 million EU households.

Our decarbonisation projects, currently in progress, will reduce emissions by 81.5 million tonnes of CO2 per year when completed by 2030. This equates to a CO2 reduction of more than 30% compared to 2018 levels, exceeding the EU’s target of a 55% reduction compared to 1990 as set out in the European Green Deal. Green steel is by far the most important material to enable a circular, carbon-lean, and environmentally responsible economy.

What are the major challenges facing the transition to carbon-lean, ‘green steel’ in Europe? What needs to change to support this transition?

The steel industry is committed to transitioning to green steel. Still, there are some challenges that need to be addressed to ensure that this happens while maintaining the EU industry’s competitiveness.

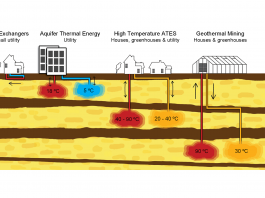

One key challenge is ensuring access to sufficient, cost-competitive fossil-free energy and critical raw materials, such as steel scrap. This requires a deep rethink of the EU electricity market design, which needs to go far beyond the current proposal of the European Commission in order to deliver internationally competitive energy for industrial decarbonisation. Furthermore, the steel sector needs priority access to hydrogen and the related infrastructure as it has the highest CO2 abatement potential compared to other sectors, and this is especially the case during the initial phase when hydrogen is scarce.

Another crucial aspect of supporting the transition to green steel is to provide better-tailored and more certain EU funding and financial incentives, coupled with faster processing of applications, as well as support for the rollout of low-carbon steel projects. Establishing lead markets for green steel and green products through public procurement, quotas, ambitious greenhouse gas (GHG) thresholds, or GHG pricing for final products based on their lifecycle emissions is also essential.

The steel industry produces more CO2 than any other heavy industry

Last but not least, we need a trade policy that levels the playing field with global competitors. The EU has become a major net steel importer, losing 26 million tonnes of production capacity between 2009 and 2020 while doubling imports to 30 million tonnes and halving exports by 15 million tonnes. To address this, we recommend maintaining the EU steel safeguard, promoting an EU-US Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel that effectively tackles global steel excess capacity while incentivising steel decarbonisation in other regions, and adopting a solution for EU steel exports before the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) kicks in in 2026. CBAM needs to be implemented in a way that it sets strong standards for steel imports. By addressing these challenges, the transition to green steel can be achieved in a way that benefits both the climate and the economy.

What role can innovation play in the transition to green steel?

Innovation is deeply ingrained in steel’s DNA, having shaped the modern world in countless ways, from skyscrapers to high-speed trains and high-tech medical equipment. There are currently over 3,500 steel grades, of which 75% were developed in the last 20 years.

The green steel transition began 20 years ago: innovation does not happen overnight but needs to be nurtured over time. Steel company programmes and EU funding schemes, such as the Research Fund for Coal and Steel or the EU Innovation Fund, have played and can play a significant role in fostering innovation in groundbreaking steel technologies. The EU’s Clean Steel Partnership will add another impetus to this development. However, funding remains difficult to access, with short application timelines and a mismatch between permitting procedures and the lifecycle of steel decarbonisation projects.

Furthermore, overly restrictive criteria that hinder technology neutrality or do not allow for a stepwise approach in terms of greenhouse gas abatement pose additional obstacles. Therefore, we should reconsider existing EU funding and financial programmes to ensure that available resources are used in synergy and programmes are simplified and easily accessible. Nevertheless, pure innovation alone is not enough to bring about change. To promote innovation in practice, we must also significantly increase support for the rollout of breakthrough technologies at an industrial scale, going beyond research, development and innovation (R&D&I), and focusing not only on capital expenditures but also on access to cost-competitive energy and hydrogen.

This is even more crucial in light of the steel-focused industrial policies in other regions. With the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the US has laid the ground for reduced-cost production of green technologies and green steel in particular. Current limitations on the calculation of the funding gap in the EU need to be addressed to match the level of incentives provided by our international competitors. In this context, we welcome European Commission President von der Leyen’s proposal for a European Sovereignty Fund as one of the structural solutions for strategic sectors under the Green Deal Industrial Plan. Contracts for Difference and public guarantees should also be considered as potential solutions to provide cost-competitive hydrogen and electricity.

What initiatives does EUROFER have in place to support the acceleration of green steel?

The European steel industry is on an ambitious path to cut carbon emissions by 55% by 2030 and to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, in line with the EU climate targets. To this end, the sector has implemented a range of initiatives to support the acceleration of green steel production.

One key initiative is the development of a large number of low-carbon projects across all major EU steel-producing countries, which have the potential to abate CO2 emissions by 81.5 million tonnes per year by 2030 if the right conditions are in place. All these projects – over 60 in 12 countries – have a Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of at least seven out of nine. Currently, their financial needs until 2030 are estimated at €31bn for capital expenditures (CapEx) and €54bn for operating expenditures (OpEx), totalling €85bn.

However, a major challenge for the transition of the steel industry is the availability of cost-competitive fossil-free energy carriers, especially electricity and hydrogen, as well as the necessary infrastructure for CO2 transport and storage. These low-carbon steel projects will require an estimated 75 TWh of electricity for the operation of steel processes and about 2.12 million tonnes of hydrogen, corresponding to about 90 TWh of electricity, if this hydrogen is produced via water electrolysis. This amounts to 165 TWh of decarbonised electricity by 2030, comparable to double the yearly consumption of Belgium. Therefore, a supportive legislative framework that effectively addresses carbon leakage both during and after the implementation of these projects is essential for their success.

EUROFER is also committed to securing access to ferrous scrap, which is an essential material for the production of green steel. The EU should consider adding scrap to the list of critical raw materials, and scrap exports should be allowed only to third countries with the same climate ambition and environmental and social standards equivalent to those of the EU.

Please note, this article will also appear in the fourteenth edition of our quarterly publication.