The Royal Osteoporosis Society’s Alison Doyle speaks to Innovation News Network about finding a cure for osteoporosis.

In the UK, an estimated 3.5 million people are living with osteoporosis (2.8 million of which are women). As a result of reduced mobility and ability to complete activities of daily living, individuals who have suffered a broken bone caused by osteoporosis may rely on informal caregivers, such as family members or friends.

The Royal Osteoporosis Society (ROS) is the only UK-wide organisation dedicated to finding a cure for osteoporosis and improving the lives of everyone affected by it.

Innovation News Network speaks to Head of Operations & Clinical Practice at the ROS, Alison Doyle.

Can you start by giving us an introduction into osteoporosis?

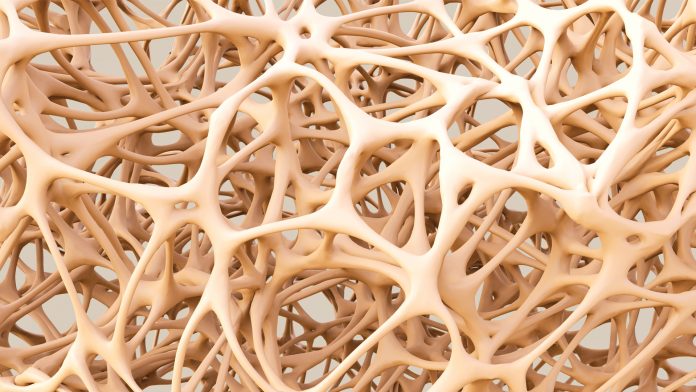

Osteoporosis is a condition where your bones lose strength, making you more likely to break a bone than the average adult. There are a number of known risk factors (such as sex, genes, ageing, low body weight and smoking) which cause bones to lose strength – osteoporosis occurs when the struts that make up the mesh-like structure within bones become thin, causing them to become fragile and break easily, often following a minor bump or fall.

An easily broken bone is often the first sign that your bones have lost strength, and half of women and 20% of men over the age of 50 are expected to break a bone as a result of osteoporosis. One of the most-common broken bones caused by osteoporosis is the wrist – often the result of putting an arm out to break a stumble or fall. Other bones commonly broken when bones lose strength are those in the spine (spinal fracture) and the hip. There are more than 76,000 hip fractures each year in the UK, which have a significant impact on those affected; during the first year after their fracture, half of those who previously walked unaided will no longer be able to walk independently.

Unfortunately, treatments for other diseases/conditions can cause osteoporosis, including treatments for coeliac disease, anorexia, cancer, epilepsy and HIV. However, genetics play the largest role in determining the potential size and strength of our skeletons; research shows that if one of your parents broke their hip, you are more likely to break a bone yourself.

What are some of trends in the treatment of osteoporosis? What are some of the main limitations when it comes to the treatment of osteoporosis, and how can these be overcome?

Compared to other drug treatments, treatments for osteoporosis are still quite new. For example, the main treatment for osteoporosis, the bisphosphonate, just had its 50th anniversary this year. Originally given as a daily tablet, bisphosphonates are now mostly administrated as a weekly oral tablet but can also be given intravenously as a yearly infusion. Having injectables as a form of treatment is important because as with all oral treatments, the adherence of them can be rather low. Therefore, by moving some patients from an oral tablet, over to an injectable drug delivery, it means they are getting more of an efficient treatment as we then know that they are receiving the drug.

Within the past 10 years, we have seen other osteoporosis treatments being tried and developed. Monoclonal antibodies in particular have a slightly different mode of action, as although they are injections, they are administered underneath the skin every six months rather than being delivered as an infusion. This form of drug (selective oestrogen receptor modulators, also known as SERMs), are suitable for those with a low level of kidney function as SERMs mimic the positive effects of oestrogen on bone tissue, helping to keep bone strong. Therefore, this opens up opportunities for some of the older population to be able to receive these types of treatments. In addition to this, there is also parathyroid hormone, an effective anabolic or bone formation treatment, which is administrated as a daily injection.

Unfortunately, not all of the recent developments in osteoporosis drugs have been successful. For example, over the last five years we have seen various drugs show promise and then only get so far along the different stages of moving to licence – it tends to be because of the side effect of cardiac issues. For example, a couple of years ago a treatment didn’t get European Medicines Agency (EMA) licensing because of some cardiac issues with a certain cohort of the population, however it has been licensed in Canada and America. That was really a disappointing decision for those with the condition because it was acknowledged that they couldn’t have it due to those certain side effects, and there are certain others who might have benefited from being able to have this treatment. This is going to appeal but we are not sure when that will be.

In terms of the limitations that come alongside treatments for osteoporosis, there is a limited portfolio of treatments. This is made worse by the fact that we have no other drugs currently in the pipeline and drugs can take up to 12 years before they are ready to be put on the market. It is also really important to choose the right treatment, for the right person, at the right time. Despite the availability of effective preventative therapies and management approaches for fragility fractures, more than 50% of UK men and women aged 50 years or above do not receive appropriate fracture prevention care in the year following a fracture.

We also know that these drugs are not lifelong; we have to decide, given someone’s risk of fracturing, when it is the best time to start (as with other drugs) and then have a yearly review. There are risk calculators that help us determine someone’s 10 year risk of further fractures; these and clinical judgement influence decisions on when to commence treatments and the first year and three to five yearly review.

What are some of the latest developments at the ROS?

A significant part of the charity’s work is providing support services to people living with osteoporosis, and working with the NHS and healthcare professionals so that the best quality services are available to everybody who needs them.

We have championed Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) since 2014, an effective, evidence-based model for service delivery that was born in Glasgow 20 years ago. FLSs identify people with their first broken bone, give them a bone health assessment and assess their future risk of fracture. This means that they receive the best possible osteoporosis advice and bone health support quicker than ever before, reducing the risk of more breaks. Subsequent fracture risk is highest in the first two years following an initial fracture, when there is an imminent risk of another fracture at the same, or other sites. This is why it is critically important to identify patients as soon as possible after fracture to optimise fracture prevention treatments and keep the person from having another fracture.

That is something we have been very much at the forefront of. Our regional teams work with clinical leads and commissioners to support the development and improvement of FLS across the UK. For those individuals who are identified through FLS as having osteoporosis and are given appropriate medication, the risk of further fracture can be reduced by up to 70%.

Since the launch of our FLS programme, 28 new services have been started across the UK. They serve almost 10 million people and it’s estimated that over five years, these new services could prevent 3,000 hip fractures and save the NHS and social services providers around £61m. Currently in the UK, we have 55% coverage of this scheme, with Scotland recently achieving 100% coverage and Northern Ireland isn’t far behind. We’re working to ensure that there is equity in access to services; if you break your wrist in London, you are not currently getting the same level of service that you would if you were in Scotland. We have been really driving the FLS model of care, from business planning through to implementation, quality improvement and service transformation with the NHS and research teams. We have also developed clinical guidance to help ensure everyone is operating at the same standard.

We’ve also begun talking a lot more about ‘bone health’. Loss of bone strength and the associated pain and disability caused by broken bones is preventable in many cases. There is much that people can do to look after their bones at all ages, particularly around nutrition and physical activity. We want to maximise peak bone mass in children and prevent premature bone loss in adults, where possible preventing people from developing osteoporosis. We aim to do this by: influencing and collaborating with national and local policy makers to make the prevention of osteoporosis a priority; developing clear, simple and evidence-based messages on how to achieve good bone health, working with other organisations to communicate these effectively; and supporting and motivating people of all ages to take proactive steps to achieve good bone health.

Working towards a cure

We continue to implement our research grants programme, in order to fund high-quality research into osteoporosis and bone health. In terms of prevention, we have seen some really interesting research and studies, particularly around pre-pregnancy and maternal health. Some of that research has then led others to take their hypothesis, test it and then be able to go from there to research grants. Our programme has started the journey for a lot of these new researchers, as they have then gone on to get larger grants to carry on their work.

We also recently launched the Osteoporosis and Bone Research Academy, which brings together leading researchers, clinicians and academics in the field to advance scientific knowledge and work towards our vision of a future without osteoporosis. The Academy is currently building a research roadmap to review previous studies into osteoporosis and identify gaps and opportunities for further research.

We have been really bold and brave in saying that we want to work towards a cure. This is something that people with the condition have told us they really wanted to see us look at. You could define ‘cure’ in many different ways. It could mean preventing further fractures after the first, preventing all fractures following a diagnosis of osteoporosis, or even preventing future cases of osteoporosis completely. The development of more effective and safe treatments and therapies to prevent broken bones and improve the quality of life for people with osteoporosis is vital to our long-term vision. There are more than 200 causes of osteoporosis, so this work will include looking at the causes, looking at what drugs we currently have, what testing we currently use, and making sure that what we have is effective.

At the moment we are working with other organisations to identify the research gaps and be clear on priorities, including leading bone researchers, industry, government and other charities. It’s important to build up different viewpoints and bring in new talents, so we can coordinate our efforts and consider the way forward as a community.

Alison Doyle

Head of Operations &

Clinical Practice

Royal Osteoporosis Society

+44 (0)7515 574 784

alison.doyle@theros.org.uk

Tweet @RoyalOsteoSoc