Detailed telescope images of red-supergiant supernova are helping scientists learn more about the early Universe.

A team of researchers, led by the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, has measured the size of a star dating back two billion years after the Big Bang, more than 11 billion years ago. Detailed images depict the supernova cooling, a breakthrough that could help scientists discover more about the stars and galaxies present in the early Universe.

The paper, titled ‘Shock cooling of a red-supergiant supernova at redshift 3 in lensed images,’ was published in the journal Nature.

What can be learnt from the images of the supernova?

“This is the first detailed look at a supernova at a much earlier epoch of the Universe’s evolution,” said Patrick Kelly, a lead author of the paper and an associate professor at the University of Minnesota School of Physics and Astronomy.

“It’s very exciting because we can learn in detail about an individual star when the Universe was less than a fifth of its current age, and begin to understand if the stars that existed many billions of years ago are different from the ones nearby.”

The researchers found that the observed supernova was approximately 500 times larger than the Sun, and located at redshift three, 60 times farther away than any other supernova observed in this detail.

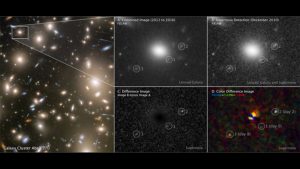

With access to the University of Minnesota’s Large Binocular Telescope and data from the Hubble Space Telescope, the team identified multiple detailed images of the supernova due to a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. This is where a mass, such as that in a galaxy, bends light, magnifying the light emitted from the star.

“The gravitational lens acts as a natural magnifying glass and multiplies Hubble’s power by a factor of eight,” said Kelly. “Here, we see three images. Even though they can be seen at the same time, they show the supernova as it was at different ages separated by several days. We see the supernova rapidly cooling, which allows us to basically reconstruct what happened and study how the supernova cooled in its first few days with just one set of images. It enables us to see a rerun of a supernova.”

Discovering more about the early Universe

The findings were combined with another one of Kelly’s supernova discoveries from 2014 to estimate how many stars were exploding in the early Universe. The team uncovered that there were likely many more supernovae than previously thought.

“Core-collapse supernovae mark the deaths of massive, short-lived stars. The number of core-collapse supernovae we detect can be used to understand how many massive stars were formed in galaxies when the Universe was much younger,” said Wenlei Chen, first author of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Minnesota School of Physics and Astronomy.