A team of computer scientists have warned of the dangers of smartphone spyware apps, saying they can easily leak sensitive personal information.

The University of California, San Diego team has also warned that spyware apps are hard to notice and detect.

These apps are marketed for monitoring children’s Internet usage and employers using work property. However, they are also frequently used by abusers to covertly spy on a spouse or a partner. These apps require little to no technical expertise from the abusers, offer detailed installation instructions, and only need temporary access to a victim’s device. This is a massive breach of data and holds many implications for cyber security.

Spyware has become an increasingly severe problem. In one recent study from Norton Labs, the number of devices with spyware apps in the United States increased by 63% between September 2020 and May 2021. A similar report from Avast in the United Kingdom recorded a stark 93% increase in the use of spyware apps over a comparable period.

“This is a real-life problem, and we want to raise awareness for everyone, from victims to the research community,” said Enze Alex Liu, a computer science PhD student at the University of California and lead author of the paper.

For their research, the team performed an in-depth technical analysis of 14 leading spyware apps for Android phones. While Google does not permit the sale of such apps on the Google Play app store, Android phones commonly allow such invasive apps to be downloaded separately via the Web. In comparison, iPhones do not allow such this, so consumer spyware apps on this platform tend to be far more limited and less invasive in capabilities.

The research, ‘No Privacy Among Spies: Assessing the Functionality and Insecurity of Consumer Android Spyware Apps,’ will be presented at the Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium in Zurich, Switzerland.

What are spyware apps and how do they collect private data?

Spyware apps commonly run on our devices without our knowledge. They collect sensitive information such as location, texts, and calls, as well as audio and video. Some apps can even stream live audio and video.

Spyware apps are marketed directly to the general public and are relatively cheap – typically between $30-$100 monthly. They are easy to install on a smartphone and require no specialised knowledge to deploy or operate. However, users need temporary physical access to their target’s device and the ability to install apps not in the pre-approved app stores.

The researchers found that spyware apps use various techniques to record data covertly. For example, one app uses an invisible browser to stream live video from the device’s camera to a spyware server. These apps can also record phone calls via the device’s microphone, sometimes activating the speaker function to capture what people are saying. Moreover, several apps also exploit accessibility features on smartphones, designed to read what appears on the screen for vision-impaired users.

Researchers also discovered that the app uses several methods to hide on the target’s device. For example, apps can specify that they do not appear in the launch bar when they initially open.

Four spyware apps accept commands via SMS messages, while two did not check whether the text message came from their client and executed the commands anyway. Alarmingly, one app could even execute a command that could remotely wipe the victim’s phone.

There are serious gaps in data security

As part of the investigation, the researchers assessed how well spyware apps protect the sensitive data they collect. They found that many of the apps use unencrypted communication channels to transmit the data they collect, such as photos, texts, and location.

Of the 14 apps the researchers studied, four had this function. That data also includes the login credentials of the person who bought the app. The researchers found that someone else could easily collect all this personal information using Wi-Fi, indicating serious data protection and security gaps.

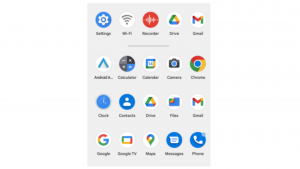

This app launcher on an Androip phone displays app icons: the Spyhuman app installed itself as the innocous-seeming WiFi icon.

Most spyware apps store the same data in public URLs accessible to anyone with the link. In some cases, user data is stored in predictable URLs that make it possible to access data across several accounts by simply switching out a few characters in the URLs. In one instance, the researchers identified an authentication weakness in a leading spyware service that would allow all the data for every account to be accessed by any party.

Moreover, many of these apps retain sensitive data without a customer contract or after a customer has stopped using them. Four of the 14 apps studied do not delete data from the spyware servers – even if the user deleted their account or the app’s license expired. One app captures data from the victim during a free trial period but only makes it available to the abuser after they have paid for a subscription.

How can we counter spyware apps and ensure our data remains protected?

“We recommend that Android should enforce stricter requirements on what apps can hide icons,” the researchers write in their paper. “Most apps that run on Android phones should be required to have an icon that would appear in the launch bar.”

In addition, as many spyware apps resist attempts to uninstall them, the researchers recommended adding a dashboard for monitoring apps that automatically start themselves. Some also automatically restarted themselves after being stopped by the Android system or after the device reboots.

To counter spyware, Android devices use various methods, including a visible indicator to the user that cannot be dismissed while an app is using the microphone or camera. But these methods can fail for various reasons. For example, legitimate uses of the device can also trigger the indicator for the microphone or camera.

The team stated: “Instead, we recommend that all actions to access sensitive data be added to the privacy dashboard and that users should be periodically notified of the existence of apps with excessive permissions.”

Next steps for data surveillance

Researchers disclosed all their findings to all the affected app vendors, but none replied to the disclosures by the paper’s publication date. Therefore, to avoid abuse of the code they developed, the researchers will only make their work available upon request to users who can demonstrate their legitimate use for it.

Future work will continue at New York University through a group led by associate professor Damon McCoy, a UC San Diego PhD alumnus. Many spyware apps are developed in China and Brazil, so further study of the supply chain that allows them to be installed outside these countries is needed.

The researchers concluded: “All these challenges highlight the need for a more creative, diverse and comprehensive set of interventions from industry, government and the research community.

“While technical defences can be part of the solution, the problem scope is much bigger. A broader range of measures should be considered, including payment interventions from companies such as Visa and Paypal, regular crackdowns from the government, and further law enforcement action may also be necessary to prevent surveillance from becoming a consumer commodity.”