With a focus on pure energy trade, the E-Regio project investigates different local energy market concepts for energy storage, whilst also conducting research on local flexibility trade.

At E-Regio, we investigate different local market concepts for energy. This is primarily for the pure energy trade, but local flexibility trade is also subject to research. An overview of local energy markets and associated literature can be found in Sumper, 2019.1 In particular, the concepts described by Bremdal and Ilieva (2019) have been important for the type of work that has been conducted in E-Regio.2 Multiple models are reviewed and discussed regarding trade, market design and market management. Market pools, centralised operations, peer-to-peer trade, and hybrid markets which combine energy exchanges with flexibility services are also described. Common to most of the models is that they are only supported by simulations.

In the ERA-Net funded project ‘E-Regio’, the aim has been to demonstrate a full-scale implementation of market models suited to different business models. One concept addresses a centralised approach designed to offer flexibility to the Swedish frequency market, as well as supporting local energy trade when flexibility sale is not demanded or when other opportunities become available.

Another demonstrator is located in Skien, Norway. This market is organised around the Skagerak football stadium. The local market concept implemented here applies a fully distributed market design with peer-to-peer trade and the ability to mix exchanges of energy with ancillary services that can benefit the local grid owner. The distributed approach will be described here.

Market concept and physical installations

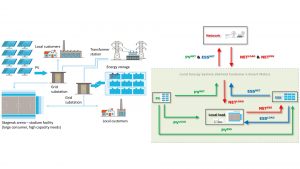

The physical installation at Skagerak consists essentially of a 5000m2 PV panel with 800kWp divided into six different sections, two major loads, and a battery (ESS) with a capacity of 1000kWh and 800kW. In addition to this, it can have a restrained or open access to the grid. The physical topology and alternative energy flows are shown in Fig. 1.

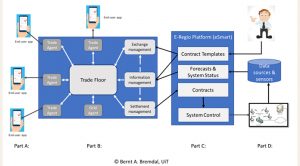

The market design applied is largely based on principles defined by Mengelkamp and Garrtner et al., 2017.3 Each of the major devices, such as the ESS, is supported by an agent, whilst game theoretic principles rule the trade. A peer-to-peer trade concept is also applied. The market behaviour of an agent that represents a device, can be controlled by means of an app. The app user defines a simple strategy of engagement by specifying an upper and lower limit for bids and asks. This largely defines the market strategy that the agent applies. In addition to this, the user and agent both have access to various services that are offered by the market platform.

Each device is provided with predictions of how much energy they would need or be able to supply for the next trading period. In addition, they are aware of the historic accuracy of these predictions and the current state of both the central market and the grid situation. The idea is that local energy trade can operate within the constraints defined by the current spot price and unit grid tariffs for regular energy use and on-grid feeds. Bids and asks are based on the predictions that are made available. When the market opens it works, similar to a bazaar, the pairing of traders is done arbitrarily. If a seller’s offer is lower than the buyer’s initial bid, a settlement can then be established. The clearing price will be based on the buyer’s bid. The volume demanded does not need to match the supply, and the surplus, or deficit, becomes subject to a new deal.

If a deal cannot be made, the agents try to pair up with others. If sellers and buyers are not successful during the first round of negotiations, they need to adjust their offers. This depends on the increments that have been defined. A selling agent needs to stay calm, hoping that a buyer may ramp up its offer, or it may reduce its sales price a notch or more. Similarly, the buying agent may stay idle for the next round or increase its bid price. The worst a seller can do is to sell to the grid – this is because it gives the lowest gain. A buyer can never do worse than what the grid can offer. Over time and under stable conditions, the average clearing price will converge towards a theoretical optimum. That is the theory that should be proved. Another objective is to make sure that both pareto optimality and fair deals for all can be achieved.

The need for more market rules and fine-tuned design

Interestingly, early tests show that there is much more to it than the basic concept supported by simulations that are made transparent. Despite the fact that full-scale use and associated testing have not started yet, the need for additional design rules have still surfaced.

It makes a big difference whether or not the information on the battery’s state of charge is shared with the rest of the market or not. This is where the benefit of full-scale testing with real people and real economies can be spotted. More of this will be tested in the remaining part of the project which will be concluded before 2021.

References

- Sumper, A. 2019. Micro and Local Power Markets. Wiley, 2019

- Bremdal, B and Ilieva, I. 2019. Micro markets in microgrids, in A. Sumper (Ed), Micro and Local Power Markets. Wiley, 2019

- Mengelkamp, E., Garttner, J., and Weinhardt, C. 2017. The role of energy storage in local energy markets. 14th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM)

Co-Authors

Kristoffer Tangrand and Asbjørn Danielsen, University of Tromsø, Norway

Eivind Gramme, Skagerak, Norway

Bernt A Bremdal

Project Manager

E-REGIO project

Smart Innovation Norway & University

of Tromsø

bernt.bremdal@smartinnovationnorway.com

https://www.eregioproject.com

Please note, this article will also appear in the second edition of our new quarterly publication.