Dr Ron Daniels, Founder and Chief Medical Officer of the UK Sepsis Trust, details the realities of sepsis in the UK today and explains what we can do to help reduce the number of cases and preventable deaths.

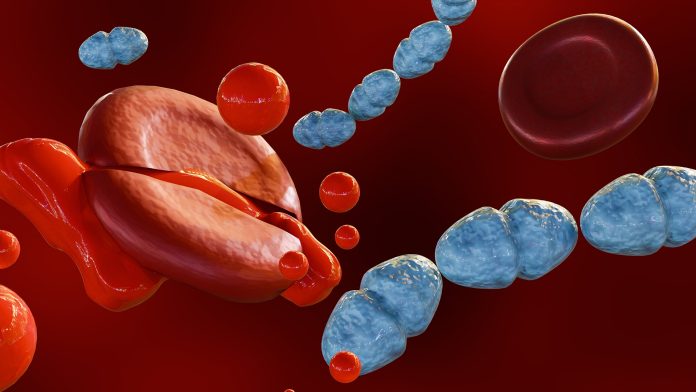

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body’s response to an infection injures its own tissues and organs, catapulting the immune system into overdrive. Estimated to cause up to 11 million deaths globally each year, sepsis is a major global health threat. Despite the staggering statistics, the seriousness of the condition is often underestimated and it is therefore vital that awareness on the topic is heightened as much as possible.

Established in 2012 by NHS Consultant Dr Ron Daniels, the UK Sepsis Trust works to raise awareness of the condition with the goal of reducing the number of preventable deaths and improving outcomes for sepsis survivors. The organisation does this by educating healthcare professionals, raising public awareness levels, providing support for those affected, and instigating political change.

Editor Georgie Purcell spoke to Dr Daniels to realise the true picture of sepsis cases in the UK and to learn what needs to be done to help combat the issue and reduce the amount of preventable deaths.

What are the realities of sepsis in the UK today?

Sepsis is estimated to affect 245,000 people across the UK every year, claiming 48,000 lives. For context, that’s slightly more hospital admissions with sepsis than we see with heart attack every year and more deaths than we see with stroke – or with bowel cancer, prostate cancer and breast cancer combined. It’s a really significant problem.

Is the seriousness of sepsis underestimated? What are the misconceptions surrounding it?

Sepsis can affect people of any age, irrespective of whether they have underlying illnesses. It can arise as a complication of any infection.

Sepsis presents in myriad different ways and, for any one individual, the chance of survival is as low as 75%. This is not only a life-threatening medical emergency, but it is also one of the most time critical we see.

There are many misconceptions. One of the most common is that sepsis is primarily a condition of the old. It’s very true that, the older we are the more we are prone to developing sepsis. However, the reality is that, because the population is largely made up of people in the prime of their life, we see as many adults of working age admitted to hospitals with sepsis as we do of retirement age. Sepsis is more common in very young children, particularly ex-premature and premature children. However, there are far more children of school age than there are of preschool age. So again, we see as many children admitted to our hospitals every year with sepsis who are of school age as we see pre-school children.

Another misconception is that this is a hospital-associated problem. The reality is very different. More than 80% of episodes of sepsis in the UK start with infections that are contracted outside of hospital. These are primarily community-acquired infections, like pneumonia, urinary tract infections (UTIs), or even something as simple as a cut, bite or sting. Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) make up the remaining 20%. Some of those are avoidable, but some are not.

What should people know about what to look out for and what to do if signs are present?

We need to trust our instincts and be prepared to advocate for ourselves or those close to us.

As I’ve said, sepsis can present in many different ways and is not an easy condition to spot. In some people, it develops very rapidly, and they go from being relatively well one day to very sick the next. In the majority, however, it develops more slowly. Most people gradually deteriorate, and identifying that time point at which we need to seek urgent help can be challenging.

Similarly for health professionals, there are conditions out there that mimic sepsis and it can therefore be difficult to spot. For GPs for example, amongst the many people presenting every year with symptoms of fever, identifying the odd patient who has sepsis can be challenging.

If someone you love – or you yourself – are deteriorating with an infection, and particularly if something doesn’t feel right, you must be prepared to go to 111 online or make an appointment to see the GP and ask if it could be sepsis.

If you think someone is seriously sick, there are six key symptoms to look for, and they spell the word sepsis:

S for slurred speech or confusion;

E for extreme pain in the muscles or joints;

P for passing no water in a day;

S for severe breathlessness;

I for “it feels like I’m going to die”; and

S for skin that’s mottled, discoloured or very pale.

If any of those six signs are present alongside an infection, you must go to A&E immediately because it is a medical emergency and every hour counts.

Could training for health professionals be better surrounding the signs of sepsis?

Health professionals today are routinely trained in recognising and treating sepsis. That wasn’t the case 20 years ago, so things have improved. However, training is often out of date and not reinforced. Ten years on for example, when someone is embedded in their career and has developed years of experience, things might have changed. We’ve seen changes in the definitions of sepsis and in treatment guidelines. If people aren’t aware of what to look for today, they’re putting patients at risk.

It’s very difficult to call for sepsis training to be mandatory, but organisations need to consider whether they’re adequately preparing their staff to recognise and treat sepsis or whether things can be improved. The UK Sepsis Trust has eLearning resources available to any organisation that might benefit from them.

What is needed to raise more awareness about the dangers of sepsis? What can the government do to support this?

Given that sepsis claims more lives than stroke every year and that it is as much of a medical emergency as a heart attack, it’s perhaps inequitable and indeed unfair that the government invested millions of pounds in campaigns for those conditions but has chosen not to invest significantly in public awareness around the symptoms of sepsis.

Not only does sepsis claim lives, it also delays return to function for those people who do survive. Almost half of people who survive are still not back at work one year after they become unwell. Public awareness has the opportunity to mitigate both of these problems. It can save more lives, prevent avoidable deaths, and speed up the return to a high-quality life and productivity for people who do survive. The reality is that the government can’t afford not to raise public awareness around sepsis because, if they fail to do so, productivity is lost. It’s really important that we work together with the government to get this message out to our public.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 21st edition of our quarterly publication.