RSS-Hydro’s Dr Paolo Tamagnone and Dr Guy Schumann examine how climate change is causing a greater frequency of extreme hydrological events.

We all know that extreme hydrological events, such as floods and droughts, can happen in almost any place on Earth, and can have devastating impacts on ecosystems, human lives, and the global economy. However, few of us expected these extremes to be accelerated at a rate faster than predicted by climate models.1

The first two years of the 2020s have borne witness to this tragedy in almost all countries across the globe with massively prolonged droughts and devastating flood events of unprecedented impact. Now, we clearly start to see the anthropogenic climate change signals in disasters as they unfold.2

Rising temperatures cause a range of extreme hydrological events

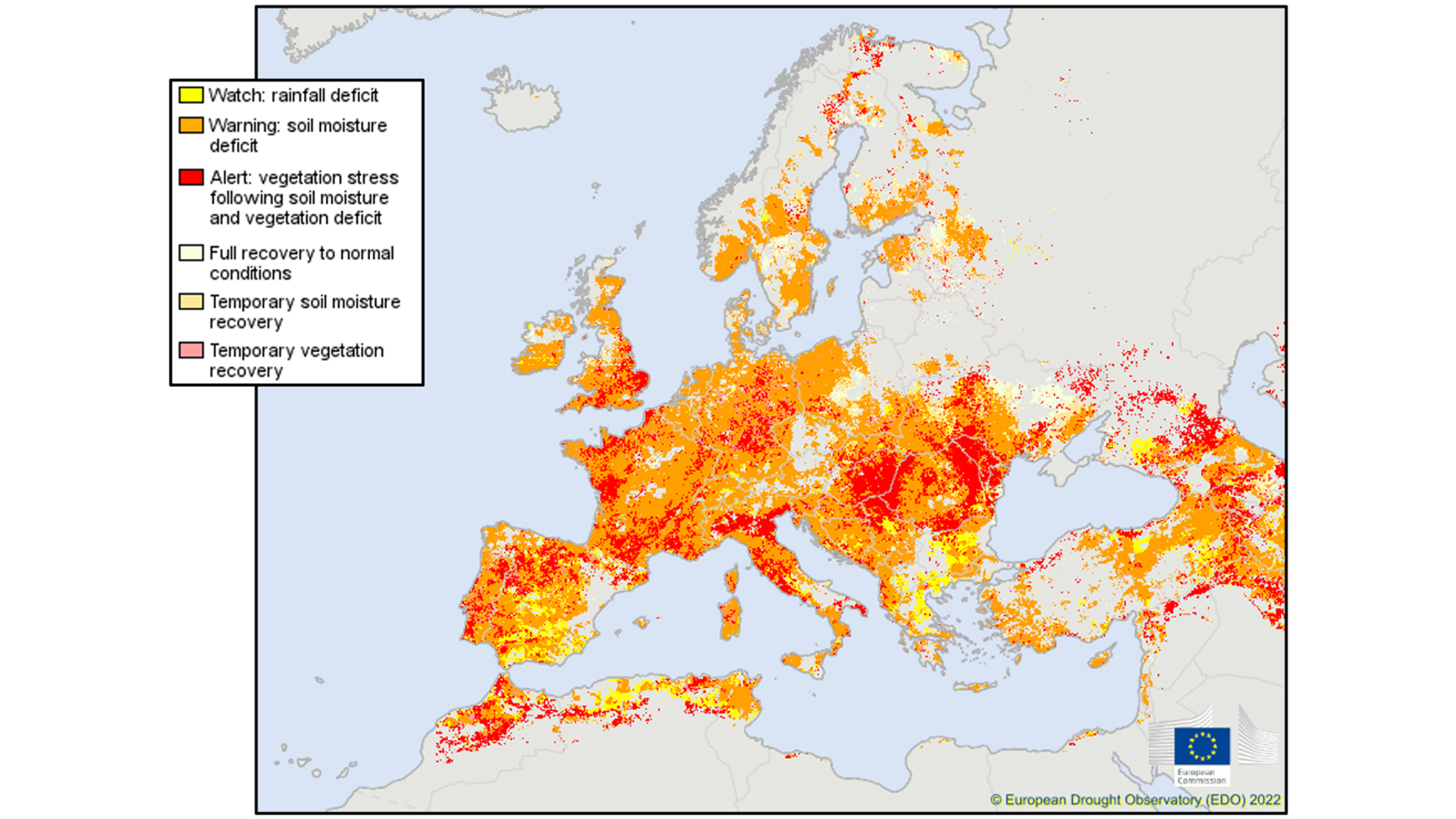

For most countries in Europe, the summer months of 2022 have been characterised by prolonged extremely hot and dry conditions, with some of them exceeding even the record increases in land surface temperatures, projected to be reached only by 2050. Still, at the start of August, the European Drought Observatory assessed that “47% of the EU territory is in Warning conditions and 17% is in Alert conditions” (Fig. 1). Within and also outside Europe, especially the US, many regions have also been impacted by very large and devastating wildfires this summer.

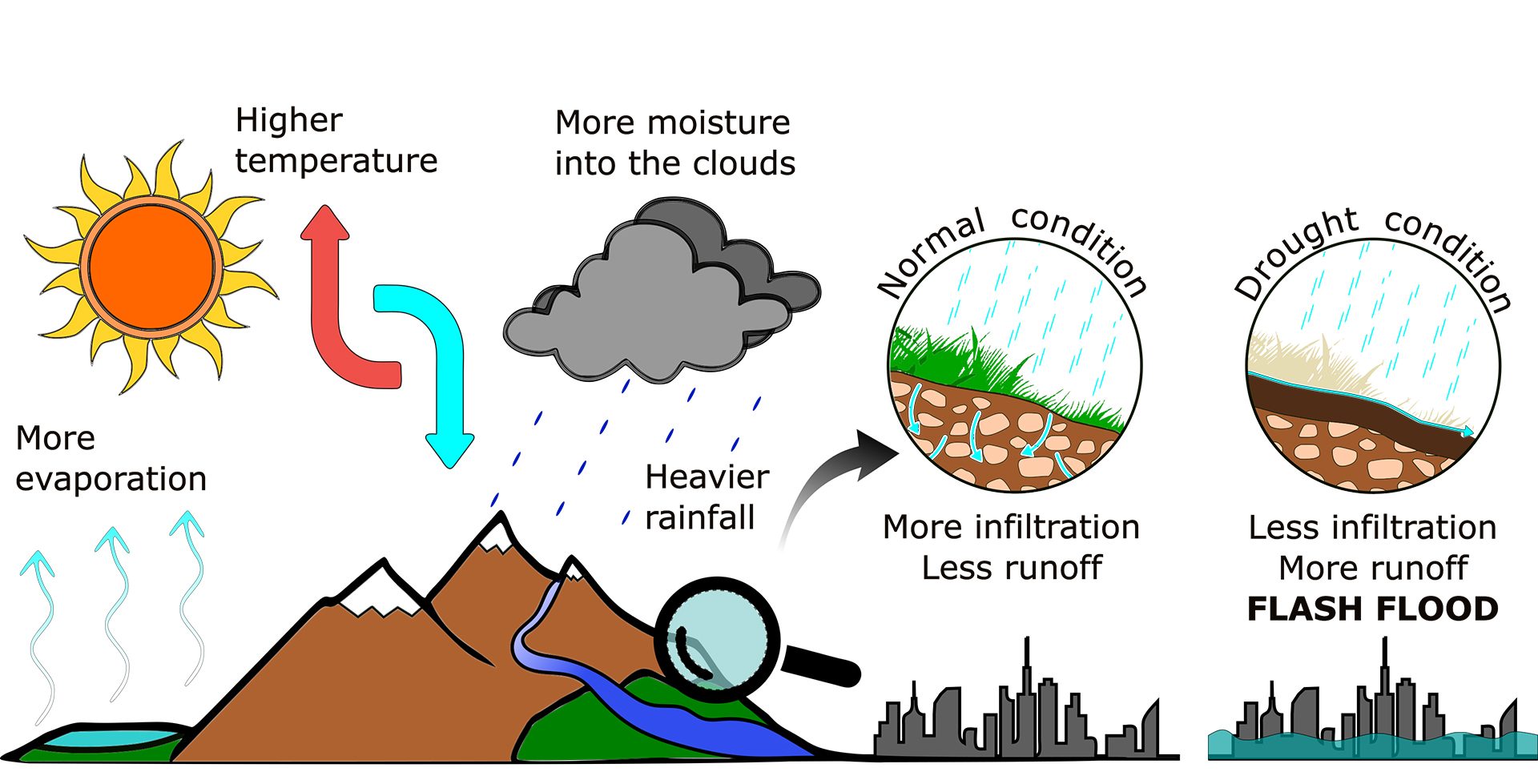

From the looks of this situation, it might seem that a consistent amount of rainfall is what we need. While this may be true for locations where wildfires are ravaging, it can be devastating when thunderstorms cause cloudbursts over very dry soils. Such cloudbursts deliver large amounts of rainfall over a very short period of time, capable of causing massive flooding. Dry, and likely crusted, soil is not able to absorb the intense precipitation and the consequent overland flow may rapidly cause flash floods.

There are two main reasons that explain the paradoxical bond between a flood, which manifests itself as an excess of water, and a drought, which represents a deficit of water (Fig. 2). More intense and longer heat waves that cause droughts also increase the rate of evapotranspiration from vegetation and force much greater evaporation from water bodies than usual. This ultimately results in a much higher quantity of water vapour content in the atmosphere. The higher temperature of the Earth’s surface warms up the atmosphere which is able to hold more moisture. Once the critical point is reached, a large amount of vapour condenses, and heavy intense cloudbursts can occur.

The threat is not limited to the skies above us, however, as the land surface beneath us also holds the unexpected. After an intense and prolonged dry spell, the vegetation covering the soil dies and it is no longer able to protect the soil from solar radiation with its canopy, nor can it preserve a healthy soil structure with its roots anymore. This exposes the soil to be literally ‘baked’, forming a hard layer on top, which is almost waterproof.

When heavy raindrops fall on such an impervious blanket of soil, they are repelled and do not infiltrate the soil. With nowhere else to go, the rainfall ponds on the surface or runs off following the topographical gradient. The risk of fast surface water runoff is greater in complex, hilly terrains where the overland flow moves faster and may accumulate quickly, leading to flash floods.

It is clear that rising global temperatures increase the moisture the atmosphere can hold, resulting in storms and heavy rains, but paradoxically also cause more intense dry spells as more water evaporates from the land and global weather patterns change. These changes to the hydrological cycle can deliver stronger, longer droughts and flash floods of unprecedented impacts. These changes in climate also bring such hazards to parts of the globe that have not seen or experienced such phenomena in living memory. It is thus difficult to point to a region or country that would not face such extreme hydrological events in the very near future with a need to manage the devastating consequences.

Mitigating the impacts of a changing hydrological cycle

According to the World Bank, floods and droughts have affected 3 billion people since the beginning of this millennium.3 The World Bank further argues that societies need to adapt, and governments must prioritise, accelerate, and scale up their response mechanisms in this decade. This requires innovative governance and risk management to navigate uncertainty, reduce duplication, make more efficient use of public resources, and protect communities, economies, and ecosystems.

In other words, as a global society, we urgently need to become more resilient and be better prepared against the devastation hydro-meteorological events can cause. We should definitely do this now, given the very apparent increase in frequency with which these hydrological events are recently occurring. One of the biggest mistakes we can make as an interconnected, global One Earth is to believe that these extreme hydrological events are rare and have, therefore, a very low probability of repeating themselves soon. We have had so many events following each other year after year in the last decade, that their probability of occurrence is constantly being revised by nature itself.

Implementing far-reaching measures

Of course, an obvious difficulty we face is that impacts from droughts and floods can be very localised but with far-reaching consequences. Therefore, any protection, action, and planning need to happen at the level of impact but, at the same time, such measures need to be reaching far beyond that level, and they need to be long-lasting as well as sustainable in order to be effective.

Looking at the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their many targets and indicators, thriving to achieve them together seems like the obvious, and maybe even the only choice we have as a global society to try and live a sustainable future. These SDGs are seen by many as overambitious, which is understandable.

Nevertheless, if we are serious about reaching at least some of the defined targets in the coming years, then we need to act now in concerted efforts. This must be achieved through strong and strategic joint ventures among governments, NGOs, research institutions, universities, large corporates, private sector SMEs, and investment funds, so that we can maximise innovation to develop the technologies needed for building sustainable solutions to limit the negative impacts of climate change and socio-economic inequalities.

References

1. Tollefson J. Climate change is hitting the planet faster than scientists originally thought. Nature. 2022 Feb 28.

2. Wehner, M., Sampson, C. Attributable human-induced changes in the magnitude of flooding in the Houston, Texas region during Hurricane Harvey. Climatic Change 166, 20 (2021).

3. Browder, Greg; Nunez Sanchez, Ana; Jongman, Brenden; Engle, Nathan; van Beek, Eelco; Castera Errea, Melissa; Hodgson, Stephen. 2021. An EPIC Response: Innovative Governance for Flood and Drought Risk Management. World Bank, Washington, DC. © World Bank.