The Executive Chair of the UK’s Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), Professor Mark Thomson, discusses the recent update to the European Strategy for Particle Physics and the role that the UK particle physics community played in its development.

This year, the European Strategy for Particle Physics, which CERN describes as ‘the cornerstone of Europe’s decision-making process for the long-term future of the field’ has been updated, with the key scientific priorities identified as being the continued exploration of the high-energy frontier and a more in-depth study of the Higgs boson, which was discovered in 2012 at CERN.

The UK has a strong heritage in particle physics and was actively involved in developing the strategy update. In light of this, The Innovation Platform spoke to Professor Mark Thomson, the Executive Chair of the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), part of UK Research and Innovation – the UK body which works in partnership with universities, research organisations, businesses, charities, and government to create the best possible environment for research and innovation to flourish.

STFC, one of the UK’s research councils, has a broad science portfolio and works with the academic and industrial communities to share its expertise in materials science, space and ground-based astronomy technologies, laser science, microelectronics, wafer scale manufacturing, particle and nuclear physics, alternative energy production, radio communications and radar.

We asked Professor Thomson about the European Strategy for Particle Physics, with a focus on the role that the UK community plays and how the UK’s priorities align with the strategy.

What role did the UK particle physics community play in developing the European Strategy for Particle Physics? How do some of the strategy’s elements reflect the ambitions of the UK community?

The European Strategy for Particle Physics was developed by the European Strategy Group, which has representatives from all of CERN’s member nations. The UK had two representatives in the group: I represented the national laboratories, and Professor Jonathan Butterworth represented the academic community. As such, we had a strong voice in the group, and we worked with the other members to develop and refine the Strategy.

From the UK perspective, we engaged the scientific community here through a number of so-called ‘Town Meetings’, where we held open discussions. We also asked our advisory panels to formulate what the UK position was in terms of going into the European strategy. It was a very interesting process, and one which worked very well.

Broadly speaking, the European strategy update is perfectly aligned with the views of the majority of the UK particle physics community, and we are very happy about that.

Were the UK’s priorities shared by the research communities in the other CERN member countries?

There is always diversity in the voices around the table, which is a good thing. Nevertheless, there was a general consensus when it came to the direction we needed to take. For instance, the overarching need for a Higgs Factory was fairly clear, as was the longer-term ambition to explore the highest energies. It was more a question of how that all comes together. And while there were sometimes different perspectives from the member countries and their communities, these were typically differences in emphasis, rather than of opinion as to the objectives themselves.

What are your hopes for the HiLumi LHC, and what role would you like to see UK scientists play, perhaps in both the physical engineering side of upgrading the LHC and also the science that comes afterwards?

Much of the work that is needed to upgrade the LHC is handled by CERN. However, the UK does have a HiLumi LHC project where, in collaboration with CERN, we contribute to the upgrade with the expertise we have developed on several specific and high-tech elements of the machine.

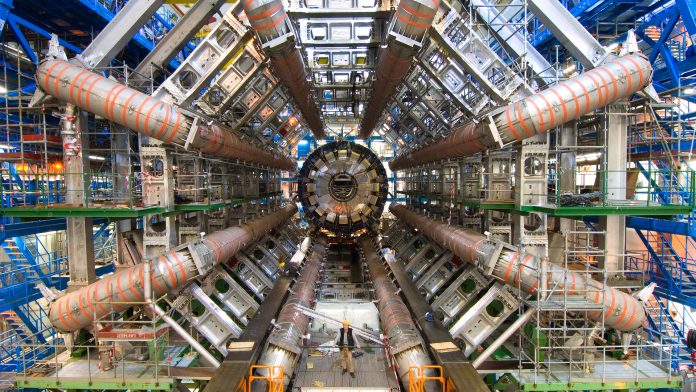

In terms of the science, the UK community has always had a strong role at the LHC. We are, of course, a major player in the Atlas collaboration, CERN’s general-purpose detector that we hope will play an integral role in the discovery of supersymmetry and dark matter. The UK also plays a very important role in the development of the CMS detector, as well as in the physics exploitation of the data from that, while we also have a major role in the LHCb detector, with the UK accounting for just under 25% of the collaboration there.

UK scientific leadership across the major LHC experiments continues to be very strong, something that is evidenced by the fact that we have held a number of spokesperson positions in these major collaborations over the years. Of course, the UK academic community has also benefitted considerably from its participation in CERN, and there are numerous examples of where British scientists have played major roles in the ground-breaking science taking place there, the UK involvement in the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012 being a case in point.

As you have mentioned, the updated European Strategy argues that ‘an electron-positron Higgs factory is the highest-priority next collider for the longer term.’ However, this requires advances in areas such as detector and sensor technologies. Is there a strategy in place to ensure UK industry as well as scientists are involved here? Is there enough support for Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) etc. who would like to operate in this space?

There are perhaps two aspects to this. Firstly, a Higgs factory will require accelerator infrastructure, whether that is at CERN or in Japan, which is also a possibility. Regardless of the location, it is often very difficult for SMEs to engage directly with a project of this scale.

Having said that, the UK has a programme for the development of superconducting RF technology, which may come to play a role here. The first deliverable from this was for the European Spallation Source, and we are working with other European partners to build up the capability of this and are working with industry on projects as we progress towards a gradual increase in scale.

It is perhaps easier for smaller businesses to be involved when it comes to detectors, and that might be because of the way we fund the development of detector systems for big projects, in that we involve both academia and industry. This is because while the academic drive is crucial, and while the funding will come through, for example, the STFC, many universities are unable to construct very large parts for detector systems, and so they have to work together with industry partners. As such, a part of our roster when we build big detector systems is to make sure the academic community engages with industry to deliver.

Of course, that isn’t always easy, and there are a few key technologies where we do have constraints in the UK and where engaging with a wide range of SMEs can be very difficult. But if industry is involved at an early stage of the technology development, then it really helps further down the line.

Would it be possible to develop an environment for this sector in the UK that is similar to that which has been created (and supported) for the space sector?

The space sector is important for the STFC. For instance, we have RAL Space at the Harwell Campus, and we are building connections with industry. However, I don’t believe that there is enough demand for something similar to be established around particle physics.

It may be possible, however, to create Centres of Excellence for the development of sensor technologies, for instance. That is because these technologies have much broader applications than just in particle physics; particle physics may be the place where you push them to the extremes, but they also have wider industrial applications. Indeed, there is an open dialogue around that, and we have had a number of internal projects where we have developed sensor technologies for particle physics which have spun out into other areas.

It is also important to mention Business Incubation Centres (BICs) here, which are designed to incubate small companies around particular sectors. STFC hosts a BIC with CERN (as we do with the European Space Agency) for businesses involved in particle physics detectors. Of course, this is at a relatively small scale in comparison to what is being done with the space sector, but it nevertheless demonstrates that we are actively working to spin out technologies that have been developed for particle physics into broader industrial applications.

Do you feel that physics beyond/without colliders (particularly, for instance, regarding lower energy experiments to compare precise measurements with clear predictions from theory) should be more of a priority moving forwards?

I completely agree that particle physics is not just about colliders. Indeed, my own background is primarily in neutrino physics, and while you do accelerate neutrinos, they are not used in a collider experiment. And, of course, there are major dark matter searches which are not collider based, such as the LZ Dark Matter Experiment, in which the UK is heavily invested.

When we look at particle physics from the UK perspective, we want to be involved in programmes which are as broad as possible, and so we do invest in these non-accelerator areas. That being said, we also acknowledge that collider physics has been at the heart of particle physics for decades and is an absolutely essential part of the field, even if it is not the only part, and so we ensure that we are involved here, too.

The UK is quite strong in the non-collider physics area, whether it be dark matter experiments or neutrino physics. Of course, one of CERN’s main strengths is that it is one of the only places where there is a major collider experiment, and so that is clearly a main focus of the European strategy update. And so, while physics beyond colliders is also a part of the strategy, the main emphasis is on the very highest energies, because that is where CERN is unique and has global leadership.

Does the UK have a presence in many neutrino experiments, such as IceCube and Km3Net?

The UK has a strong neutrino physics community, but we do not have a large presence in IceCube and Km3Net. We have focused our investments on long-baseline neutrino oscillation experiments such as MINOS and T2K. Most recently, the UK has made a very large commitment to the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE) in the US – the collaboration for which I used to lead.

Concerning theory, the European Strategy update argues that ‘Europe should continue to vigorously support a broad programme of theoretical research covering the full spectrum of particle physics from abstract to phenomenological topics.’ How would you like this being addressed in the UK? Is it something that needs to be left to institutions to decide? Or can the STFC play a role in defining priorities?

That is a very good question. Of course, we fund theory through our consolidated grants, where institutions apply for grants for specific pieces of work. But in an interlinked way we also support the Institute for Particle Physics Phenomenology (IPPP) in Durham, which was established some years ago to strengthen the connection between the theory and experimental communities.

The UK has been at the forefront of linking theory to experiments; and that was a strategic decision ahead of what was likely to come out of the LHC, where direct contact between theorists and those working on the experiments is crucial to exploiting the LHC data. It was therefore encouraging to see that the European strategy suggested that the UK has been doing the right thing.

Finally, how will the STFC continue to support the UK physics community, and how do you expect to evolve?

It will be business as usual to some extent, in that we conduct frequent reviews of our programme, building on the advice of the scientific community, and that goes from horizon scanning to tensioning decision making – deciding which projects should be funded, which is always essentially a question of resources.

On the other hand, we will also be looking at new ways of operating within UKRI. For instance, working with the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) we have recently launched the Quantum Technologies for Fundamental Physics Programme (QTFP), which is an exciting initiative that involves a different way of looking at fundamental science by starting to use emergent quantum technologies to do experiments in different ways, typically at smaller scales.

The forward-looking nature of this is incredibly exciting; it is designed to explore how we can we do something different as quantum technologies are developing and becoming more mainstream. It also represents a great opportunity for the UK to get ahead of the game in this sector.

Professor Mark Thomson

Executive Chair

Science and Technology Facilities

Council (STFC)

Tweet @STFC_Matters

www.stfc.ukri.org/

Please note, this article will also appear in the third edition of our new quarterly publication.