David Proulx, Chief Product Officer at SkyWatch, discusses how the Earth Observation industry can make use of the power of satellite imagery as a valuable intelligence tool.

According to industry analysts, the Earth Observation (EO) industry is expected to grow 100x in the next ten years. It is helpful to consider where all that growth will come from. Will it be driven by the traditional consumers of EO, those GIS (geographic information system) ‘geeks’ who spend their days doing band-math indices and making ESRI maps?

Certainly, in part, but a picture (a human-readable one) can be worth way more than a thousand words in the eyes of the proper recipients – most of whom will come from industries many standard deviations away from the mean of legacy GIS. And this becomes particularly true with the emergence of no-code AI, computer vision tools, and the power of satellite imagery to detect, classify, and count things.

There is much talk about the transparency afforded by Earth Observation as a driver for change and action in areas such as climate change, peace and security, and other critical areas that affect life on Earth.

How can businesses unlock the power of satellite imagery?

With multi-modal, high-resolution sensors revisiting every square inch of the Earth multiple times a day, there is nowhere to hide from the power of satellite imagery – especially when the data collected by those sensors are available at market rates to anybody with a credit card and a web browser.

We can use hyperspectral imagery (HSI) to keep tabs on those nasty carbon emitters in the oil and gas industry; we can use synthetic aperture radar (SAR) or middle-wave infrared (MWIR) to watch military forces amass on a border under cover of darkness and foliage. That’s powerful. But who wants to pay for it?

What if we extend the concept of EO-derived transparency to the value chains that support every good and service delivered by the economy’s private sector? What can we see, and who wants to pay for it?

We call this the ‘commercial intelligence’ sector, and we’ll illustrate with an ‘earthy’ example from the prosaic but $13bn agricultural sector.

Let’s say that we have a feedlot operator in the rural US. Her feedlots span many acres and contain thousands of heads of beef cattle at any given time. What difference does the power of satellite imagery make—and to whom?

Producers

This is their livelihood: the number of cattle, fence integrity, the comings and goings of suppliers, employees etc., all matter.

Commodity owners

Our feedlot operator doesn’t necessarily own the livestock they are managing; they are owned by someone else outright or via a derivative investment (typically a considerable agri-business/food production concern).

This person wants the contracted producer to know what they are doing.

Input providers

Silage bunker operators and feed transporters are interested in what’s happening on the feedlot.

Lenders

Intensive agriculture is a highly leveraged business; a financial institution will have loaned the cash.

Insurers and reinsurers

Agriculture is an inherently risky venture; weather, supply chain, disease, etc., can all impact yields.

Somebody – or, likely, a consortium of somebodies – is underwriting this risk. How they model that risk, and the premiums paid by our producer to manage that risk, can be derived from point-in-time or time series analysis.

Public regulators

Agriculture is a highly regulated practice. Regulators are interested in whether:

- The producer has enough liquid manure lagoons based on the head of cattle in the feedlots; and

- If they are the right distance from waterways.

Environmental NGOs (non-government organisations)

While not for profit, funding for these NGOs is secured based on action. What better way than harnessing the power of satellite imagery to see what’s going on?

Competitors

Our producer’s competitors are interested in the goings-on at the feedlot. Counting cows in the feedlot or monitoring the comings and goings of trucks from their loading docks using Earth Observation can provide valuable competitive insights.

Commodity traders

These people make money based on a given commodity’s spot-market value and pricing trends. A change in the number of cows could be a signal not just for beef futures but also for derivatives in the various inputs (corn, potash, etc.)

Leveraging EO will have significant impacts on businesses

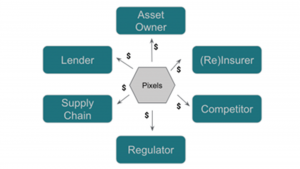

So, whether we are talking about cows, corn, oil wells, wind turbines, rail cars at a mine, or cars in a parking lot at a major retailer, the point is that there are multiple stakeholders in any commercial operations, for each of whom the transparency afforded by EO can have a material financial impact. Put differently, the same pixels can provide significant value up, down, and across the value chain. We think it generalises something like this:

At scale, any industry that follows this structure – and that is most industries – can see a significant impact from harnessing the power of satellite imagery and small predictive signals. However, the marginal effect of an information advantage (knowing sooner and acting sooner) can be enormous.

Notably, the marginal cost of that information advantage continues to decrease. Within the next decade, it will be entirely possible for a mid-sized private sector company in any of the industries we discussed to own and operate their satellites or high-altitude platform systems (HAPS), like balloons or drones, to get helpful information from the data those sensors capture. The traditional value chains will collapse in a way that creates more economic value, not less.