Astronomers have used NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope to shed light on the mystery of wandering star formation.

Wandering stars that are not gravitationally tied to any one galaxy in a cluster can be found in clusters of hundreds or thousands of galaxies. These stars wander among galaxies emitting a ghostly haze of light. For several years, astronomers have pondered how these wandering stars become so scattered throughout the cluster. Leading theories include the possibility that the stars were stripped out of a cluster’s galaxies, or they were tossed around after mergers of galaxies, or they were present early in a cluster’s formative years many billions of years ago.

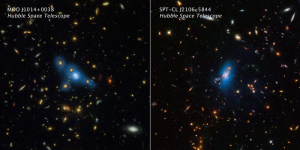

Now, a recent infrared survey from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has shed light on the mystery, with the new observations suggesting that these wandering stars have been around for billions of years.

The study, ‘Intracluster light is already abundant at redshift beyond unity,’ is published in the journal Nature.

Revelations from the Hubble survey

The survey included ten galaxy clusters as far away as nearly ten billion light-years. The measurements had to be made from space as the intracluster light is 10,000 times dimmer than the night sky as seen from the ground.

It was revealed that the fraction of the intracluster light relative to the total light in the cluster remains constant, looking over billions of years back into time. “This means that these stars were already homeless in the early stages of the cluster’s formation,” said James Jee of Yonsei University in Seoul, South Korea.

Stars can be dispersed outside of their galactic birthplace when a galaxy moves through gaseous material in the space between galaxies, as it orbits the centre of the cluster. During this process, drag pushes gas and dust out of the galaxy.

However, the results of the new Hubble survey mean that this mechanism can be ruled out as the primary cause of the intracluster star production, as the intracluster light fraction would increase over time if stripping were the main player. The new Hubble data shows a constant fraction over billions of years.

“We don’t exactly know what made them homeless. Current theories cannot explain our results, but somehow, they were produced in large quantities in the early Universe,” said Jee. “In their early formative years, galaxies might have been pretty small and they bled stars pretty easily because of a weaker gravitational grasp.”

The importance of discovering the origin of wandering stars

“If we figure out the origin of intracluster stars, it will help us understand the assembly history of an entire galaxy cluster, and they can serve as visible tracers of dark matter enveloping the cluster,” said Hyungjin Joo of Yonsei University, the first author of the paper. Dark matter holds galaxies and clusters of galaxies together.

If the wandering stars were produced through a comparatively recent pinball game among galaxies, there would not be enough time for them to disperse throughout the entire gravitational field of the cluster. Therefore, they would not trace the distribution of the cluster’s dark matter. If the stars were born in the cluster’s early years, however, they will have fully dispersed throughout the cluster. Astronomers could then use the wandering stars to map out the dark matter distribution across the cluster.

This new technique complements the traditional method of dark matter mapping by measuring how the entire cluster warps light from background objects due to a phenomenon called gravitational lensing.

Detection of intracluster light

Fritz Zwicky first detected intracluster light in 1951 in the Coma cluster of galaxies. As this cluster is one of the nearest clusters to Earth, the ghost light was detected by Zwicky with a modest 18-inch telescope.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s near-infrared capability and sensitivity will deepen the search for intracluster stars further into the Universe, and should therefore help solve the mystery.