Laboratory astrophysics uses advanced techniques like powerful lasers and plasma experiments to simulate and study extreme cosmic conditions, enabling researchers to explore phenomena such as star formation and the dynamics of celestial bodies that are otherwise beyond our reach.

The universe is a large and complex system, where the most fascinating astrophysical events take place in distant galaxies or hostile environments that are beyond our physical reach. Stars are formed in stellar nurseries – huge molecular clouds light years away, while black holes and neutron stars exist in regions of extreme gravity where traditional observational techniques struggle.

Even within our own solar system, planetary interiors remain largely unexplored. Take Mars, for example – when the Perseverance rover landed in 2021, it carried a drill capable of reaching just three inches below the surface. Beyond that shallow layer, the planet’s interior remains a mystery. If understanding nearby planets is this difficult, how can we hope to study exoplanets, neutron stars, or stellar nurseries?

Space is vast, profoundly fascinating, and difficult to study

The challenge isn’t just about distance; it’s also about time. Some of the most dramatic astrophysical events, like supernovae or gamma-ray bursts, are incredibly rare, meaning astronomers may only witness a handful per century.

Other key processes – such as star formation, planetary evolution, or black hole accretion – unfold over millions to billions of years, far beyond a human lifespan. This raises a fundamental problem: how can we study astrophysical events that we can’t observe in real-time or physically reach?

To overcome these challenges, our group turns to laboratory astrophysics – where lasers, plasma physics experiments, and extreme compression techniques allow us to recreate and study the conditions found in distant stars, planetary interiors, and cosmic explosions right here on Earth. Using giant lasers, we can squeeze, shock, heat, ionise, and magnetise matter to replicate the exotic environments found in stars, planetary interiors, supernova shocks, and accretion disks.

Instead of waiting millennia for a black hole to evolve or struggling to peer deep into a planet, we can simulate these extreme environments in the lab – compressing time and space into an observable, testable framework.

Reproducing these extreme conditions demands some of the world’s most powerful lasers, capable of compressing energy into tiny volumes within fractions of a second. The National Ignition Facility, for example, houses the world’s most energetic laser, capable of delivering over two million joules of energy in a single shot – enough to momentarily compress the material to pressures exceeding those inside giant planets like Jupiter.

hair, recreating the extreme conditions found in stars and fusion reactions. Photo credit: Wikipedia/Damien Jemison/LLNL

Similarly, the Linac Coherent Light Source and the European X-ray Free Electron Laser generate ultra-bright X-ray pulses, allowing scientists to probe the structure and behaviour of matter under extreme-density conditions.

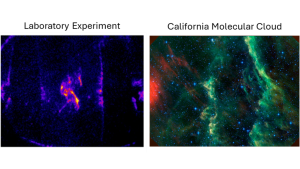

One of our recent examples is the study of turbulence in star formation – here lab experiments have revealed how chaotic gas motions shape galaxies and star nurseries. By recreating the chaotic motions within molecular clouds in a controlled laboratory setting, we were able to uncover new insights into how turbulence shapes the birth of stars – one of the fundamental processes influencing the structure of galaxies and planetary systems across the universe.

Understanding how stars are born

Stars are born in turbulent clouds of gas and dust, where gravity, shock waves, and magnetic fields battle to shape their formation. These vast molecular clouds span tens to hundreds of light-years and are chaotic environments where turbulence regulates the collapse of interstellar matter.

Unlike the familiar turbulence of air or water on Earth, astrophysical turbulence is often supersonic, meaning gas motions exceed the local speed of sound. This leads to the formation of shock waves, which play a crucial role in determining how gas fragments into stars. Understanding this process is vital for explaining the rates and efficiency of star formation across the universe.

Observing these turbulent motions directly is difficult. Molecular clouds evolve over millions of years and are often obscured by interstellar dust, limiting what telescopes can capture. To bypass these challenges, we turned to laboratory astrophysics, using high-powered lasers to generate supersonic plasma jets in a controlled setting. In our experiment, we collided with two laser-driven plasma jets, creating a turbulent region that closely mimicked the conditions inside star-forming clouds. This experiment was performed at the Central Laser Facility at Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the UK, using the Vulcan laser, a high-energy laser system capable of producing the extreme conditions necessary to replicate astrophysical turbulence.

We observed thin, shock-driven structures forming in the plasma – closely resembling those found in interstellar molecular clouds. These high-density regions, where hot plasma compresses into narrow filaments, are key sites where gravity takes hold, ultimately leading to star formation.

This experiment provided direct evidence that supersonic turbulence in astrophysical settings naturally organises gas into dense, elongated structures, confirming long-standing theories about how turbulence influences star birth. By bringing star-forming turbulence into the lab, we are bridging the gap between theory and reality – bringing us closer to understanding how the galaxies we see today came to be.

Unlocking the Universe in the Lab

Laboratory astrophysics is revolutionising how we explore the cosmos. By recreating extreme cosmic environments using lasers, plasma physics, and high-energy-density experiments, scientists can directly study processes that shape the universe, such as the turbulent birth of stars – all within the controlled conditions of a laboratory.

As experimental capabilities continue to evolve, future studies will push the boundaries of what we can simulate, offering new insights into black hole accretion, nuclear fusion, and the fundamental forces shaping our universe – without ever leaving Earth.

However, the power of these experiments extends far beyond astrophysics. The most powerful lasers on Earth are opening new frontiers in materials science, high-energy physics, and extreme engineering. In the next few articles, I’ll give a sneak peek into the exciting physics and engineering that can be explored using the biggest lasers in the world. Topics will include:

- Listening to the depths of planets – how measuring the speed of sound inside extreme materials is revealing the structure of planetary interiors.

- The world’s longest thermometer – using 3km-long X-ray lasers and inelastic X-ray scattering to measure temperature in ways never before possible.

- A 200-year-old prediction, finally tested – how modern experiments have confirmed Joseph Fourier’s theory of interfacial thermal resistance in extreme plasmas.

- Creating the hottest solid on Earth – pushing materials to their limits and exploring the physics of superheated matter.

- Bond hardening in extreme conditions – why some materials become stronger as they get colder.

Each experiment pushes the limits of what’s possible, bringing the universe’s most extreme conditions into the lab.

Please note, this article will also appear in the 22nd edition of our quarterly publication.