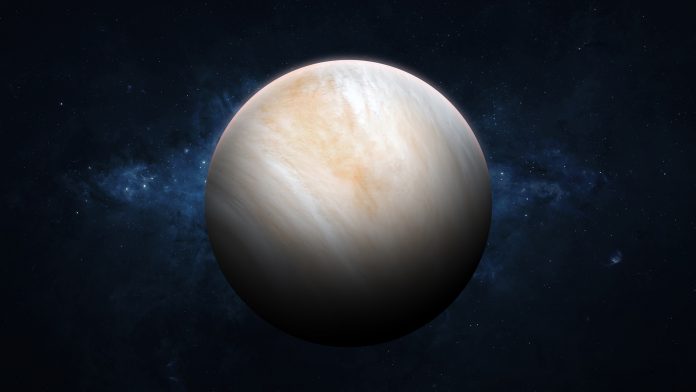

University of Cambridge researchers have unveiled a missing component in the clouds of Venus.

Scientists know that the clouds of Venus are predominately made of sulphuric acid droplets, with water, chlorine, and iron. The concentrations of these components vary depending on the height they are sat within Venus’ atmosphere.

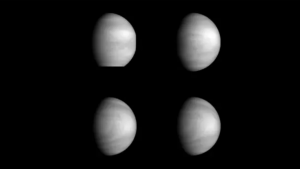

Until now, however, researchers have been unable to identify the missing component that would explain the clouds’ patches and streaks that are visible in the UV range.

In a new study published in Science Advances, the Cambridge University team synthesised iron-bearing sulphate minerals that are stable under the harsh chemical conditions in Venus’ clouds.

Spectroscopic analysis showed that a combination of two minerals, rhomboclase and acid ferric sulphate, is responsible for the UV absorption feature.

The team synthesised several different minerals

The team used knowledge of Venus’ atmospheric chemistry to synthesise several iron-bearing sulphate minerals in an aqueous geochemistry laboratory.

The synthesised materials were then suspended in varying concentrations of sulphuric acid to monitor the chemical and mineralogical changes. From this, the team narrowed down the minerals to rhomboclase and acid ferric sulphate.

The spectroscopic features of these materials were then examined under light sources specifically designed to mimic the spectrum of solar flares.

“The only available data for the composition of the clouds were collected by probes and revealed strange properties of the clouds that so far we have been unable to fully explain,” said Paul Rimmer from the Cavendish Laboratory and co-author of the study.

“In particular, when examined under UV light, the Venusian clouds featured a specific UV absorption pattern. What elements, compounds, or minerals are responsible for such observation?”

Mimicking the extreme clouds of Venus

The research was collaborated with a photochemistry lab at Harvard. Their team provided measurements of the UV absorbance patterns of ferric iron under extremely acidic conditions to mimic the more extreme Venusian clouds.

The scientists are part of the Origins Federation, which aims to promote collaborative projects like this one.

“The patterns and level of absorption shown by the combination of these two mineral phases are consistent with the dark UV patches observed in Venusian clouds,” said co-author Clancy Zhijian Jiang, from the Department of Earth Sciences, Cambridge.

“These targeted experiments revealed the intricate chemical network within the atmosphere, and shed light on the elemental cycling on the Venusian surface.”

Learning more about Venus in the future

Rimmer concluded: “Venus is our nearest neighbour, but it remains a mystery.

“We will have a chance to learn much more about this planet in the coming years with future NASA and ESA missions set to explore its atmosphere, clouds, and surface. This study prepares the grounds for these future explorations.”