Jacob Larkin, Marketing Coordinator at Lanes Group plc, outlines the importance of implementing stronger legislation to tackle microplastic pollution.

Plastic pollution is one of the defining environmental challenges of our current era. It is estimated that around 400 million metric tons of plastic are created every year, a number that is only increasing – and the world is still struggling to find a sustainable way of processing and disposing of plastic waste.

A recent report estimated that more than 171 trillion pieces of plastic are currently circulating in the world’s oceans. Most people are aware of the impact that discarded plastic bottles and packaging have on the environment, but many may not realise that one of the most common forms of plastic pollution is also one of the smallest.

Microplastics are tiny particles or fragments of plastic that measure less than 5mm. Despite their microscopic size, they are doing significant damage to the environment, polluting our seas and rivers, and exacerbating existing problems with the over-stressed sewer and drainage network.

As the UK’s largest privately-owned specialist drainage and wastewater contractor, Lanes Group sees the impact of plastic pollution on the country’s drains and waterways on a daily basis, and has launched a campaign called Microplastics Out of Our Drains (MOOD) to raise awareness of the issue. Here, we will explore the causes and impact of the rise of microplastics, and identify the key steps that must be taken to remedy it.

The scale of the current microplastic pollution problem

Due to their small size and sheer ubiquity, it is almost impossible to accurately estimate how many microplastic particles can now be found polluting our environment. These tiny plastic fragments have been created in vast quantities over the years, and are now so deeply embedded in the environment that it would now be impossible to remove them.

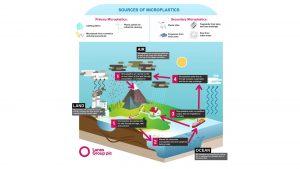

There are two main sources of microplastics in the environment:

- Primary microplastics, which are created intentionally at a microscale to make consumer products last longer, or to alter their quality in some way. Examples include the microfibres found in clothing or personal care products.

- Secondary microplastics, which are created through the gradual breakdown of larger plastic items over time. Discarded carrier bags or pieces of packaging that are littered in the ocean will gradually degrade, releasing microplastics over an extended period.

Estimates from the Marine Conservation Society suggest that of the 11 million tons of plastic entering the ocean every year, around one million tons can be accounted for by primary microplastics. Moreover, a study from Kyushu University in 2021 estimated there are 24.4 trillion pieces of microplastics in the world’s upper oceans, with a combined weight of 82,000 to 578,000 tons.

In reality, it is likely that even this massive figure is a significant underestimate. Microplastics can now be found everywhere in the world, including in snow close to the peak of Mount Everest, the Mariana Trench – the deepest point of the ocean – and even in the once-pristine Arctic.

This could be having a number of negative effects on the natural world:

- Microplastics have been found to be continually consumed by marine life at all stages of the food chain, including fish, plankton, whales, dolphins, turtles, and seabirds. In a 2015 study, 63% of shrimp in the North Sea were found to contain synthetic fibres.

- Humans also ingest microplastics into their bodies in large quantities, either by consuming seafood contaminated by oceanic microplastic, or through the water they drink or air they breathe. This could be harmful in various ways, from cell death to allergic reactions.

- Plastic particles have also been shown to be infiltrating the human body at a deep level – they can enter the bloodstream and have been found in the placentas of unborn babies.

Additionally, the trends that cause microplastic pollution have been shown to have knock-on consequences for our built environment, including a significant impact on our essential drainage and water processing systems.

Products such as wet wipes, nappies, period care products, cotton buds, and face masks have a high plastic content, which means they do not break down when flushed down the toilet or disposed of down the drain.

This causes fatbergs and other stubborn sewer blockages to form, which obstruct and damage pipes and sewers. This leads to a greater risk of flooding and requires time and money to be spent on unblocking and repairs.

As these items slowly erode in the drains, they become one of the main sources of secondary microplastics in wastewater. This microplastic content must be carefully removed during the wastewater treatment and purification process, or else the plastic will make its way to our natural waterways, adding to the existing pollution of our rivers and seas.

An underestimated problem

According to a recent survey of just under 1,000 people carried out by Lanes Group, the scale of the microplastic problem is widely underestimated by many members of the public. Although the survey revealed that 72% of respondents had heard of microplastics prior to taking part in the research, only 6% felt they were well-informed or had any expertise on the topic.

The survey also highlighted a number of common misconceptions:

- 61% believed that the amount of microplastic released into the environment each year was 1.5 million tons or less, when the true figure is 15 million tons. This shows that the scale of the problem is commonly underestimated by a factor of ten.

- Similarly, only 60% estimated the total amount of plastic waste released into the environment annually at 30 million tons or less, when the real figure is closer to 300 million.

- Only 32% realised that the erosion of road markings is a source of microplastics, when in fact around 7% of all microplastic pollution comes from road markings alone.

These stats demonstrate why greater efforts are needed to educate the public on the microplastics issue, particularly in terms of how widespread the problem has become, and the steps that will be needed to make a meaningful difference in tackling the trend.

Why stronger legislation is needed to tackle microplastic pollution

In years past, much of the focus of environmental campaigns was placed on consumer action, and emphasised the individual lifestyle changes that can help to drive large-scale progress. In more recent years, however, there has been a growing awareness that the most effective interventions should centre on large-scale policy changes led by governments and industry, which can tackle pollution at its source.

Microplastics are a case in point, as the best way of reducing their impact on our ecosystem is to simply stop these plastics from entering the water environment in the first place. Over the last few years, there are signs that lawmakers are coming to understand this – but more progress is needed.

A good example of this is the UK Government’s decision to ban microbeads, a specific type of tiny plastic particle previously used in cosmetic products. Thanks to the Environmental Protection (Microbeads) (England) Regulations 2017, manufacturers of cosmetics and personal care products for the UK market are now banned from adding microbeads to rinse-off products such as face scrubs, toothpastes, and shower gels, and retailers can no longer sell such products.

This ban undoubtedly represents good progress, but at the same time, it has clear limitations. The legislation covers only microbeads within personal care products and cosmetics, which represent only 2% of microplastics released into the world’s oceans. As such, Lanes Group’s MOOD campaign is recommending a more aggressive legislative approach to curtailing the spread of microplastics in our drains and waterways.

We believe that governments should be taking the following actions:

- Ban all intentionally added microplastic particles in consumer or professional use products – this measure has already been proposed and is being discussed by the European Union, and other countries should follow suit.

- Implement a framework for water companies to establish regular monitoring programmes for microplastics, allowing them to track the spread of microplastic in influent, effluent, combined sewer overflows and treated sewage sludge.

- Compel manufacturers to fit microfibre filters in all new domestic and commercial washing machines, and retrofit existing commercial machines with similar filters.

- Appoint designated ministers for plastics pollution, with cross-departmental remits for controlling and preventing plastic pollution, and oversight of environmental policies relating to plastics and their polluting effects.

Estimates by the Marine Conservation Society suggest that banning microplastics could help to reduce the amount of plastic entering our rivers and oceans by around 400,000 tonnes over a 20-year period. Lanes’ research also shows that such measures would have widespread public support: 60% of those polled would be in favour of an outright ban on all intentionally added microplastic particles in manufacturing, while 89% agree that washing machine manufacturers should have to fit microfibre filters in new machines as standard.

There is no quick or easy solution to the microplastic pollution problem, but it is important that lawmakers, manufacturers, and industry bodies start to recognise the scale of the issue, and the potentially significant role they have to play in fixing it. Removing microplastics from the environment completely is an unrealistic goal at this point, but by minimising the amount of new microplastic that we release into the ecosystem, it may not be too late to curtail the long-term effects of these pollution trends.

Jacob Larkin

Marketing Coordinator

Lanes Group plc

https://www.lanesfordrains.co.uk/