Giles Dickson, CEO of WindEurope, spoke to International Editor Clifford Holt about what is needed to secure the potential of wind energy in Europe’s carbon-free future.

Active in over 35 countries and with over 400 members, WindEurope is the voice of the wind industry, actively promoting wind power in Europe and worldwide. The organisation actively co-ordinates international policy, communications, research and analysis and also provides various services to support members’ requirements and needs in order to further their development, offering the best networking and learning opportunities in the sector.

WindEurope analyses, formulates and establishes policy positions for the wind industry on key strategic sectoral issues, co-operating with industry and research institutions on a number of market development and technology research projects. Additionally, the lobbying activities undertaken by WindEurope help create a suitable legal framework within which members can successfully develop their businesses.

International Editor Clifford Holt spoke to WindEurope’s CEO, Giles Dickson, about the role of wind in Europe’s post-COVID recovery, as well as about challenges such as maritime planning and permitting, which are currently hindering the significant expansion of wind energy that Europe needs if it is to meet its carbon reduction targets.

You have said that, given the amount of investment the wind sector has seen during the COVID-19 pandemic that ‘it is clear that finance isn’t our biggest concern. We need to see more projects’. What do you see are the biggest barriers to this in Europe today?

We currently have 180 gigawatts of wind capacity in the European Union. But that needs to be increased to 1,300 GW by 2050. Most of it will be onshore – around 1,000 GW. But the EU Strategy on Offshore Renewable Energy also proposes to increase Europe’s offshore wind capacity from its current level of 12 GW to at least 60 GW by 2030 and 300 GW by 2050 as a part of the European Commission’s higher climate target of reducing emissions by 55%. The needed expansion is even more substantial when one takes into account that the vast majority of the existing 180 GW will have reached their end of life by 2050 and must be replaced by new turbines.

This means that we will need a much faster deployment of wind energy. Europe needs to build 30 GW a year over the next five years. However, at WindEurope we have looked at the project pipeline and at the volume of permits being awarded in different countries, and we estimate that Europe will only achieve 15 GW a year. If that is indeed the case, then after 2026, five years from now, the deficit must be made up.

The main reason we are not building enough new wind farms in Europe – and why we will not be building enough over the next five years – is permitting. Permitting rules and procedures are simply too complex – it takes too long to obtain a permit, and many project developers are deterred from even pursuing projects because of these difficulties. This is due, in part, to the fact that there are not enough staff working in the permitting authorities to process the permit applications.

To take Italy as an example: 50% of wind farm projects there are simply being abandoned at the moment, while the other 50% are taking, on average, six years to obtain a permit. That’s just not good enough if we want to deliver the energy transition.

What is it about the permitting rules and procedures that makes them so complex?

To begin with, there is a lot of paperwork involved. Numerous forms have to be completed for different authorities at different levels of government. Simplification and digitalisation of the whole process is needed.

Elsewhere, countries ask developers to stick to the exact technology specifications provided in the initial permit application. But when it can take six years to get that permit, in many cases by the time the wind farm is finally being built the applicant is obliged to use outdated technology. They may even struggle to find a manufacturer that is still producing the technology they outlined in their permit application. Some countries do have some flexibility here and allow more modern turbines to be installed when building begins, but many do not. This is therefore another area in which improvements are required.

Then there are certain rules that are unnecessarily restrictive. This includes the famous 10H Distance Act in Poland, for example, which banned the construction of wind power plants within a distance of less than 10 times the height of the windmills away from residential properties. The rule essentially excluded 98% of Polish territory from wind energy development. Similarly overly restrictive rules on how far from a radar installation – both civil and military – windfarms can be built are excluding large areas from wind energy development in France.

This goes some way towards illustrating that while some governments have recognised the importance of simplifying the permitting process, others have not, and we are now working with the European Commission to see if we can find ways of helping certain governments to make things easier for themselves.

And we see some positive signs. The Polish government has said it is going to soften the 10H rule and it has circulated a draft piece of legislation that will hopefully come into force later this year. Germany is supporting the replacement of ground-based radar stations by new technology. And that is just one of many reforms on an 18-point plan for permitting that Germany presented.

Under Europe’s revised Industrial Strategy, the EU wants 1,000 GW of onshore and 300 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2050 in order to deliver climate neutrality. Is this likely?

With today’s permitting rules and procedures and taking current investment levels regarding the grids into consideration, Europe will not be climate neutral by 2050. Neither will we meet the 2030 targets.

We therefore need a new approach to permitting for windfarms and we need to double grid investments. Between now and 2030, we need to invest €80bn a year in transmission and distribution networks for electricity. Currently, however, Europe is investing just €40bn. We also need changes in the way gas and electricity is taxed that incentivise consumers to switch, for example, from central gas heating to an electric heat pump.

The technology is here. But domestic consumers today pay more tax per unit of final energy consumption when they switch to electric heating in comparison to gas, and that needs to change, We need to incentivise large-scale electrification. It is the most cost-effective way to decarbonise Europe. There must be a level playing field.

For offshore wind, we have developed a new coalition with the big environmental NGOs, the Offshore Coalition for Energy and Nature, which is designed to help ensure that the massive expansion in offshore can be delivered in the most environmentally sustainable way possible. As a part of this, WindEurope is working with the NGOs on detailed protocols on, for example, the most environmentally-friendly way of installing foundations into the seabed, as well as in areas such as whether sites need to avoid bird migration routes. As Europe’s wind energy industry association, we at WindEurope recognise that we have a major responsibility to ensure that those we represent are reassured that there is an environmentally-friendly way of doing things.

How else would you like to see the Commission’s ‘Fit for 55’ help?

The European Commission has now tabled the Fit for 55 package, and it includes a higher renewables target and new rules to support the expansion of renewables. It contains changes to over 10 pieces of legislation, including the Renewable Energy Directive, the Energy Tax Directive, the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Directive and the EU Emissions Trading System.

The Fit for 55 package further reinforces the role of electrification in transport. It includes more stringent CO2 emissions standards, a ban to the sales of diesel and petrol cars by 2035 and a new target for charging stations along highways; one every 60 km. The revised Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Directive includes targets for electric charging infrastructure for light and heavy-duty vehicles and electrification targets for certain ships. The package also says that renewable fuels of non-biological origin, such as renewable hydrogen, must be 2.6% of total transport energy consumption by 2030.

The main hurdle to a rapid expansion of wind energy in Europe remains: complex rules and procedures for permitting new wind farms. WindEurope therefore calls on the European Commission to work with Member States to help them simplify their permitting rules and procedures. The EU has a key role to play here in identifying and promoting best practice.

Given that at least 37% of all spending under the Recovery & Resilience Facility (RRF) must be climate-related, what role do you see the national Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs) playing in supporting investments in wind energy?

The RRPs are going to be very important in terms of accelerating investment in key supporting infrastructure such as grids or EV charging stations, with many Member States having included these investments in their recovery and resilience plans.

Investments in ports is another important area. Both France and Poland have included this in their RRPs, which is very positive because offshore wind cannot be developed without investing significantly in port infrastructure: more space is needed, key sites need to be reinforced, and deep berths are needed for installation vessels, for instance. We estimate that investments of €6.5bn are required across Europe.

Can you tell me a little about the WindEurope 2020 report on ‘Wind energy and economic recovery in Europe; and what the two scenarios (the National Energy And Climate Plan (NECP) scenario and the Low Scenario) revealed?

In this report we looked at the different National Energy And Climate Plans, which the Member States submitted to the European Commission in 2020, to better understand how much wind energy they include and what the economic impact of that might be.

WindEurope found that if the Member States deliver on their expansion plans then there will be 397 GW of wind across the whole of Europe, which also equates to a total of 450,000 jobs in the sector, up 50% from 300,000 jobs today. However, if the Member States do not deliver on their NECPs, and if they continue with existing policies and existing approach to things like planning and permitting, then this number is reduced to 324 GW and there is actually a reduction in the number of jobs, down to 282,000.

It is important to understand that countries only deliver on their NECPs if they improve the underlying supporting policies, including those pertaining to planning and permitting, and that is the thinking behind our two scenarios.

The NECP scenario assumes that Member States have indeed delivered their NECPs. The lower scenario assumes that the countries try to implement their NECPs but they fail because they try to do so with their existing policies, which do not work.

What is the role of electricity in a net zero energy system of the future?

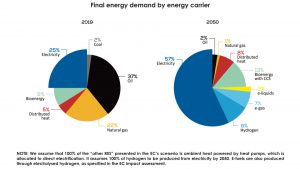

WindEurope has produced a report on how wind-based electrification will drive Europe to net zero. It concludes that wind energy can help electrify 75% of Europe’s energy demand, up from 25% today, and that this can be broken down to 57% direct and 18% indirect electrification through hydrogen and its derivatives. So wind can deliver; the technology is there and it is affordable because the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) from wind continues to come down.

The report also contains encouraging numbers for the LCOE reduction by 2030 and 2040. The report reveals that we need annual investments to rise, as previously mentioned, from the €40bn we are seeing today to €80bn in transmission and distribution networks for electricity in order to deliver this significantly more electric energy system.

We can save money on generation with lower LCOE, and we can also save money on energy consumption in industry. Indeed, the report details how far we can directly electrify different industrial sectors. Many sectors will run on 100% renewable electricity by 2050. It also details what the savings could be in terms of reduced fossil fuel consumption in industry if they were to switch from fossil-based energy to renewable electricity.

By bringing these figures together, it is possible to show that the total cost of the net zero electrified energy system is the same as today’s dirty energy system – 10.3% of GDP. That is the report’s final conclusion, which is extremely positive and which, of course, only takes into account the immediate system costs and so does not include external costs like public health, air quality, environmental impact and so on. If these external costs are added to the equation, the net zero energy system is much cheaper.

While The EU Maritime Spatial Planning Directive required coastal Member States to submit their Maritime Spatial Plans to the Commission by 31 March 2021, only six met the deadline. How important is MSP for the future of wind energy? What message would you give to Member States yet to submit their plans?

The Maritime Spatial Plans are extremely important; we can only deliver the huge expansion in offshore wind if countries take a new approach to maritime spatial planning – one that has the energy transition at its heart, rather than it being merely an afterthought. This will require those countries to think, at the very beginning, about which areas they need to set aside for the energy transition.

Maritime spatial planning has traditionally focused on where, for example, fishing needs to take place, or where the military zones or shipping lanes are, and now they also have to begin to factor in offshore renewable energy. While some countries have been active in offshore wind for some time and are therefore getting used to taking this into account in their maritime spatial planning, many others have not, and that can pose a challenge.

Offshore wind does not require a huge amount of space; the aforementioned 300 GW would take up just 7% of the EU’s maritime space. Some may feel that this is a lot, but the sector is currently barred from 60% of the maritime space and while this can be for valid reasons, we are asking some countries whether those reasons are really justifiable – do shipping lanes need to be four nautical miles wide, for example.

It is important to note that while 300 GW of wind power generation would require 7% of the EU’s maritime space, that space can have multiple uses. Certain forms of fishing, for example, can take place inside or around windfarms. We therefore need to move away from the silo-based approach to maritime spatial planning and begin to think laterally. As such, we work very closely with fishing communities and the fishing industry when we are deciding where to locate a new windfarm, and we explain that windfarms can be beneficial for fisheries because they create new breeding grounds. Fish stocks can recover, mussels can grow on the turbine foundations, and there is less disruption to the seabed as there is no dredging or bottom trawling.

Most European countries, however, still do not allow any form of fishing inside offshore windfarms. But that is beginning to change, albeit slowly, with Belgium, the UK, and Denmark now permitting it.

The fact that only six Member States submitted their Maritime Spatial Plans to the Commission on time is a shame, but at least they now have more time to think about how they can factor offshore wind into their plans.

In light of the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead, what are your hopes for the future of the wind energy sector in Europe?

We are determined to deliver the huge expansion in wind energy that the European Union needs in order to deliver the energy transition, the Green Deal, and climate neutrality. We hope that this huge expansion is made in Europe by developing a competitive European wind industry, which makes complete political and economic sense.

We want citizens and communities to take part in the energy transition; we cannot simply take it for granted to just go from 180 to 1,200 GW without engaging people. Indeed, public support for the continued expansion of wind energy is something we take very seriously as an industry association, and a key part of that is managing our own sustainability and environmental footprint.

We are also engaging with the EU institutions and national governments to ensure that the right policies and procedures are in place to deliver this massive expansion in wind energy. Furthermore, we are increasingly engaging energy consumers in order to make it as easy as possible for those who want to decarbonise in areas such as transport, heating, and industrial processes to use wind energy.

So far, as an industry we focused on building windfarms But we need to think further. We need to understand who is going to consume our energy; and we need to understand how this energy can be used to support the decarbonisation of Europe’s economy. We are therefore talking to energy-intensive sectors about how wind and, where necessary, renewable hydrogen can help to decarbonise their activities. This includes working with those in the electric vehicle space to develop the necessary charging infrastructure, and we are also talking to those in the heat pump industry as well as those looking to electrify district heating to explore how wind energy can be used there too. Corporate renewable PPAs play an important part in that.

Giles Dickson

CEO

WindEurope

+32 2 213 1811

info@windeurope.org

Tweet @WindEurope

You can find the WindEurope website here.

Please note, this article will also appear in the seventh edition of our quarterly publication.